Casey B. Mulligan is an economics professor at the University of Chicago.

The propensity of unemployed people to receive unemployment benefits reached historical highs after the 2008-9 recession and may indicate that benefit rules have more impact on the economy than ever before. The changing aggregate impact of unemployment insurance may be worth considering as Congress debates benefit extensions.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Unemployment insurance offers funds, for a limited eligibility period (now up to 99 weeks), to “covered” people who lost their jobs and have yet been unable to find and start a new job.

Some economists suggest that unemployment insurance prolongs unemployment because recipients have to give up their benefits as soon as they find and start a new job, or return to working at a previous job.

Some economists also say they believe that unemployment insurance stimulates spending because unemployed people are thought to spend most, if not all, of the money they have on hand.

But neither of these effects can operate unless people take part in the program.

Historically, many of the jobless have not collected unemployment benefits because of ineligibility, lack of awareness or unwillingness to do so.

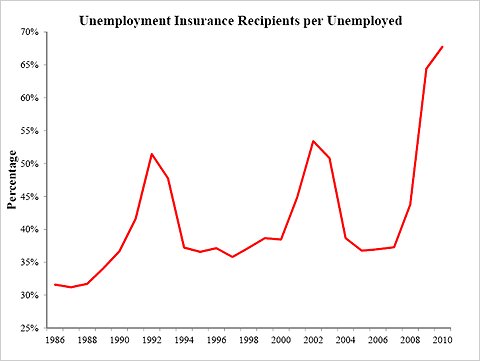

The chart below graphs the recipiency rate — the percentage of people unemployed who are collecting unemployment benefits that week — to 1986. It was calculated from weekly data, then averaged over 52 weeks to remove some of the large seasonal patterns.

The percentage is always well under 100, fluctuating from 31 to 68 percent. The peak recipiency rates seem to follow recessions; three national recessions have occurred since 1986, in 1990-91, 2001 and 2008-9. Previous studies covering the period 1960-94 found a similar pattern (although perhaps no recipiency rate peak was found after the 1981-82 recession), with a maximum recipiency rate for all 35 years of about 50 percent.

Some unemployed people cannot collect benefits because they quit their jobs, rather than being laid off. But quits are less common during recessions, one reason the recipiency rate is greatest during recessions.

Another reason that recessions can have high recipiency rates is that, by law, benefit eligibility periods are longer during recessions. Laws often increase the eligibility periods by a greater percentage than the average duration of unemployment increases, with the result that a larger percentage of the unemployed are eligible for benefits.

Among other things, the 2009 American Reinvestment and Reinvestment Act expanded eligibility for unemployment insurance by encouraging states to adopt an “alternative base period” benefit calculation rule that allowed a number of people with weak employment histories to qualify for benefits.

Long-term comparisons of recipiency rates are tricky because the data sources change and because of secular changes in the composition of unemployed, but it appears that recipiency rates were higher during 2009 than they have been in 50 years, and perhaps ever.

With such a large percentage of unemployed people receiving benefits, the potential employment and spending effects of those benefits may be greater than ever.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=fddc5be230de41065e9b27f34c633226