Casey B. Mulligan is an economics professor at the University of Chicago. He is the author of “The Redistribution Recession: How Labor Market Distortions Contracted the Economy.”

As Democrats and Republicans haggle over federal taxes and spending, another important policy tool gets less attention: regulation.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

Government has a variety of ways it can achieve its objectives, including subsidies, taxes and regulation. For example, the government might attempt to help disabled people by subsidizing handicapped-accessible buildings. Or it could levy an extra tax on buildings that are not handicapped-accessible. Or it could simply refuse to permit structures to be built, or used in various situations, without being handicapped-accessible.

All three strategies are likely to affect building activity, increase the prevalence of handicapped-accessible buildings and in so doing help people with disabilities, as intended. The first strategy is ordinarily called government spending; the second, taxation; and the third, regulation.

Private-sector activities to comply with regulation do not appear in the government budget, whereas private-sector interactions with tax and spending programs do, in terms of the amount of money they pay or receive. (Regulation does need a government budget for enforcement, but so do taxes and spending, and enforcement is distinct from the private sector’s compliance activities.)

Politicians have devised various budgetary gimmicks to help disguise what they tax and spend, and the sunset provision that led to next month’s fiscal cliff is one of them. Nevertheless, experts and even the voting public get an idea of the importance of taxes and spending in the economy by looking at budget totals and perhaps a few of the largest line items.

The same cannot be said for regulation, which lacks any official budget. Attempts have been made to quantify regulation by the number of pages of law or pages of agency rules: President Ronald Reagan once bragged that his administration reduced one area of regulation to 31 pages from 905.

However, pages can be misleading, because some words, sentences and paragraphs have more impact than others. For example, some laws, like those requiring children to attend school, have little impact because a vast majority of American families would send their children to school even if the law did not require it. Other laws, like many curfews, take up space on the books but are not enforced.

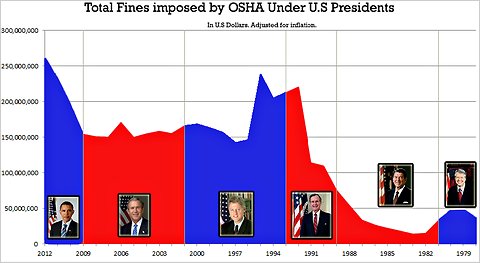

Because regulations have so far been poorly quantified, it is interesting to see a recent study of workplace regulation by complianceandsafety.com. It attempts to measure the aggregate of importance of workplace regulation by the dollar amount of fines collected by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Its chart, reproduced below, looks at the fines in reverse chronological order, and colors years according to the political party of the president in power.

complianceandsafety.com

complianceandsafety.com

OSHA fines have increased sharply since 2009. Perhaps more surprising is that the largest fine increases previously were under a Republican president (the first President George Bush) and the largest reductions were under President Bill Clinton.

As with taxes and spending, we cannot necessarily conclude that more regulation is “bad” or “good,” but it would be helpful for experts and voters alike to see a rigorous accounting for government regulation.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/26/a-budget-for-regulation/?partner=rss&emc=rss