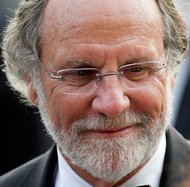

Gary Gensler entered the lion’s den on Thursday with some news that tamed the crowd of bankers.

In a lunchtime speech before a conference of international bankers, Mr. Gensler, the head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, outlined a plan to regulate overseas derivatives trading while also delaying some new rules for foreign banks. Next Thursday, Mr. Gensler said, the agency will introduce a proposal to phase in foreign compliance with derivatives regulations for “up to one year.”

Regulators would use the time to complete a broader proposal to police derivatives trading overseas. The plan, Mr. Gensler noted on Thursday, tracks an approach first floated last year by a group of bankers.

“I hope you still like it,” Mr. Gensler said with a smile, speaking in a ballroom at the Waldorf Astoria in Midtown Manhattan.

Once the rules are fully phased in, Mr. Gensler said, he expects 20 to 30 foreign banks to register with his agency. The companies include many of the big European banks in attendance on Thursday, including Deutsche Bank and UBS.

The banks have long anticipated the new oversight, which stems from the Dodd-Frank Act, the regulatory overhaul law enacted two years ago.

“Please don’t come in and say you’re surprised,” Mr. Gensler told the Institute of International Bankers. “And if you do, at least keep a smile.”

Despite his playful remarks, Mr. Gensler delivered plenty of tough talk.

In one awkward moment that came as Mr. Gensler discussed future financial collapses, he declared that “some of the banks here will not be survivors.” Bankers, eating fruit and chocolate mousse, rolled their eyes.

Undeterred, Mr. Gensler made the case for regulating derivatives trading overseas. One proposal would apply new oversight to foreign banks that conduct significant derivatives trading in the United States, as well as American banks that have foreign units.

The issue came into focus last month after the multibillion-dollar derivatives mess at JPMorgan Chase. The trades that went awry came from the bank’s London unit.

“Recent events at JPMorgan Chase are a stark reminder of how swaps traded overseas can quickly reverberate with losses coming back into the United States,” Mr. Gensler said. “Now is not the time to retreat from these much-needed reforms.”

Under the proposal, foreign banks involved in more than a very tiny level of derivatives business in the United States will become so-called swap dealers. The swap dealer status comes with enhanced capital requirements and other oversight measures.

In the speech, Mr. Gensler invoked several recent foreign blowups that hit home in the United States. The American International Group, an American insurance company that booked its risky derivatives deals out of London, would have collapsed if not for a major government bailout.

“We’ve seen this movie before,” Mr. Gensler said.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/06/14/regulator-may-grant-foreign-banks-brief-reprieve-on-derivatives/?partner=rss&emc=rss