CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

I spoke today with Diane Swonk, chief economist at Mesirow Financial, who mentioned that she has been keeping an eye on which industries and occupations are giving raises. Unfortunately, not many fall under that category.

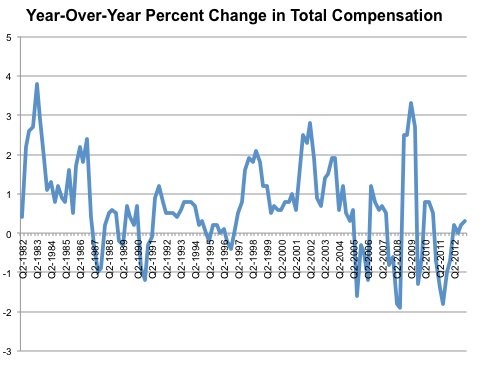

As of March, the Labor Department’s index for the cost of total compensation for all civilian workers was just 0.3 percent higher than a year earlier, after adjusting for inflation. To give some context, the year-over-year change in this index — which includes wages and salaries as well as benefits — has averaged 0.7 percent since 1982, the first year these data became available.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Numbers are adjusted for inflation by Haver.

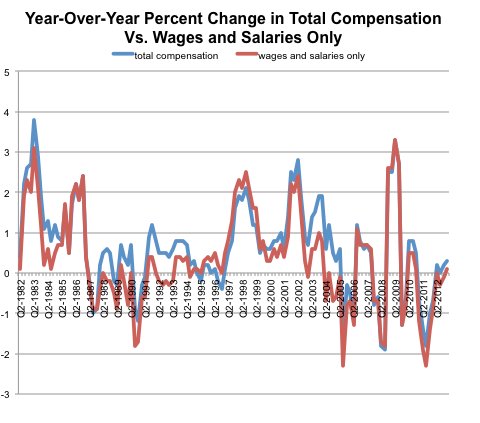

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Numbers are adjusted for inflation by Haver.

Inflation has been very low in recent years, but it has still been substantial enough to mostly wipe out the meager raises that American workers have been receiving in nominal terms. (Before adjusting for inflation, compensation rose 1.8 percent year-over-year in March, compared with a long-term average of 3.7 percent.) Workers’ raises are also slightly lower if you strip out the cost of benefits, particularly since the rise in health care costs has generally outpaced the rise in wages. That’s probably not a coincidence; growing health care costs are eating up other forms of compensation that employers might otherwise provide.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Numbers are adjusted for inflation by Haver.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Numbers are adjusted for inflation by Haver.

The lack of major wage gains across the board seems to contradict the idea that the economy is suffering from a major bout of skills mismatch. I have no doubt that employers in some industries are having trouble finding workers with relevant skills, but if skills mismatch were the primary driver of the country’s lackluster hiring in recent years, then we would expect to see many more businesses bidding up wages in pursuit of those rare skilled workers who are available.

The two categories that have shown the biggest year-over-year increases in total compensation are (1) occupations in transportation and material moving and (2) employees at junior colleges, colleges, universities and professional schools.

So what do truckers and professors have in common? Ms. Swonk observes that their jobs are both hard to either outsource or automate, unlike a lot of other occupations.

That is becoming less true for professors, though, in the age of massive open online courses, or MOOCs. MOOCs help schools cut down on labor costs by scaling up the number of students who can be taught by a single professor — in some cases, a professor they don’t even directly employ. And professors are worrying about being displaced. As The Chronicle of Higher Education reported Thursday, faculty members in the philosophy department at San Jose State University released an open letter saying they refuse to adopt a MOOC with lectures from a Harvard professor because they don’t want to enable efforts to “replace professors, dismantle departments, and provide a diminished education for students in public universities.”

On the other hand, MOOCs could still push up the overall level of wages for people employed at colleges by changing the composition of workers on those payrolls; the superstar professors whose lectures are featured in large-scale online courses will continue to be paid a lot, while the lower-wage professor jobs at community colleges and other strapped schools could be eliminated altogether, stripping out the bottom part of the pay distribution in higher education.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/02/where-the-raises-are-trucking-and-academia/?partner=rss&emc=rss