Until the mid-1980s, only a single state – and one of the smallest in population, Alaska – had set a minimum wage higher than the federal minimum. But with the federal minimum remaining unchanged at $3.35 an hour for most of the 1980s, more states began to set higher floors for wages.

<![CDATA[]]>

A closer look at big issues facing the country in the 2012 Election.

By the end of the 1980s, a dozen states had their own, higher minimum wage. By 2008, 32 states did. The number has fallen to 18 today, because the federal minimum has risen since 2008 – it’s now $7.25 an hour – and overtaken some state minimums, but the 18 include several large states. In Illinois, the minimum wage is $8.25. In California, it is $8. In Florida, it is $7.67.

As a result of these state minimum wages, the federal minimum is not as important as it once was. It applies to less than 60 percent of the population.

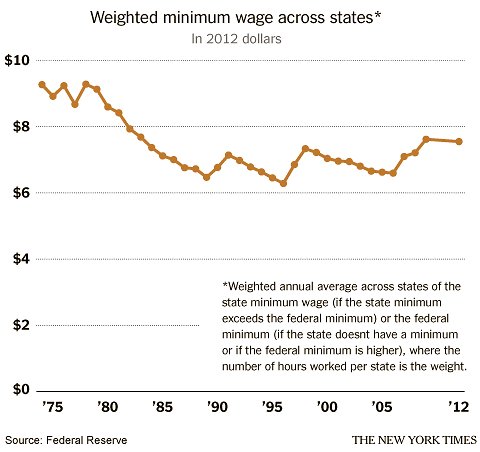

In this space, we have been examining the causes of the American income slowdown – over both the last decade and the last generation – and our recent list of 14 possible causes included the stagnation of the federal minimum wage. That stagnation certainly matters: in 1968, the minimum wage was 45 percent higher than it is today, adjusting for inflation.

But I think it’s fair to say that the minimum wage is not one of the most important causes of the income slowdown. The minimum wage instead belongs on a list of secondary causes. It probably did play a substantial role holding down the pay of low-income workers in the 1980s and in increasing inequality, as research by David S. Lee and others has found. But its role seems to have been much smaller in the last two decades.

I’ll confess that I did not expect to come to this conclusion. When we started this project, I assumed that the minimum wage would have played a larger role. If others think it has, we welcome hearing from them.

The crucial point is that the minimum wage has risen, even after adjusting for inflation, over the last 20 years. The reason it is so much lower now than in the late 1960s is that it declined so much from the late ’60s through the late ’80s.

The effective minimum wage today – a national average taking into account both the federal and state minimums – is about $7.55, which is more than 10 percent higher in inflation-adjusted terms than the effective minimum in 1990. Today’s effective minimum is also about 7 percent higher than in 2000.

Yet the overall pay of people at the bottom of the income ladder has been virtually unchanged since 1990, according to Census Bureau data. And pay at the bottom (as well as the middle) has fallen since 2000. The rising tide of the minimum wage, to use President John F. Kennedy’s formulation, has not kept most boats from falling.

Why doesn’t the federal minimum wage matter more than it does?

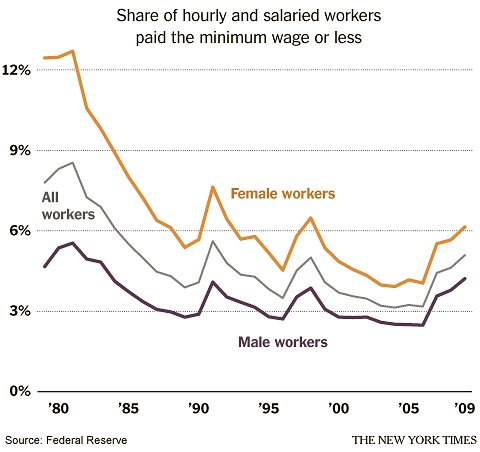

For all the economy’s problems, American society is still richer than it was a generation ago, with fewer low-wage workers. As a result, fewer are subject to the minimum wage than would have been the case in the past. The biggest changes have occurred among women.

In the 1970s, women made up the great majority of minimum-wage workers. But as women’s pay has risen, the share making the minimum wage has dropped sharply. Over all, about 5 percent of all hours worked in 2009 were paid the minimum wage or less (some businesses, like restaurants, are exempt). That was down from 8 percent of hours in 1979, according to research by David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Alan Manning of the London School of Economics and Christopher L. Smith of the Federal Reserve.

The decline is almost entirely the result of rising women’s wages. About 4 percent of men’s hours are paid at or below the minimum wage, down only slightly from 5 percent in 1979. For women, the decline was much bigger: to 6 percent, from 13 percent.

None of this is meant to suggest that the minimum wage is irrelevant. It affects not only minimum-wage workers but also those paid slightly more, who often receive raises when the minimum rises. If Congress increased the minimum wage to its inflation-adjusted 1968 level, a large number of poor people would receive a raise. Some would also lose their jobs, if their employers decided they could not profitably pay the higher wage. But research suggests that modest increases in the minimum wage do not have a large effect on employment.

All in all, a higher minimum wage would probably lead to a rise in pay for lower-income workers in general and a decline in inequality.

The 1980s help make that case in reverse. The federal minimum did not change from 1981 to 1990, causing its inflation-adjusted value to fall 30 percent during that time. Wages in the bottom of the income distribution fell sharply, even more sharply than they have in the last decade. The inflation-adjusted wage of a worker at the 20th percentile of the distribution dropped 9.5 percent from 1981 to 1990, according an analysis of government data in the forthcoming book “The State of Working America, 12th Edition,” by the Economic Policy Institute.

Mr. Lee, a Princeton economist, argues that the minimum wage accounted for “much of the rise” in inequality in the bottom part of the income distribution in the 1980s. David Card of the University of California, Berkeley, and John DiNardo of the University of Michigan have made a similar argument. Mr. Autor, Mr. Manning and Mr. Smith suggest the effect was smaller but agree it existed.

Since 1990, though, the minimum wage has risen. If you’re trying to understand why every income group except for the affluent has taken an income cut over the last decade, you probably shouldn’t put the minimum wage at the top of your list of causes.

In coming weeks, our look at other causes will continue.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/05/why-the-minimum-wage-doesnt-explain-stagnant-wages/?partner=rss&emc=rss