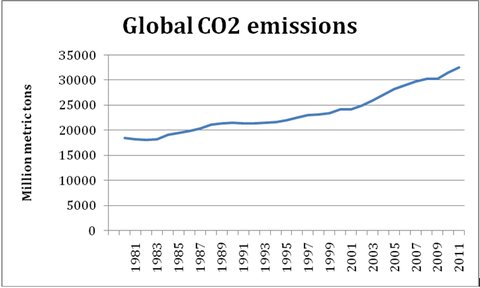

How close is the world to devastating climate upheaval? My column on Wednesday argued that the natural gas boom is helping the United States reduce its emissions of heat-trapping carbon into the air, encouraging power generators to switch to gas from the much dirtier coal. American CO2 emissions last year totaled about 5.25 billion tons — almost 13 percent less than in 2007.

But as some readers argued, the decline is so modest that it is almost irrelevant. To stop the world’s temperature from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above the pre-industrial era — considered by most climate scientists as the prudent limit — emissions must fall much faster.

In fact, keeping to the target probably requires that a good share of the world’s fossil fuel remains untapped.

Source: Energy Information Administration, Department of Energy

Source: Energy Information Administration, Department of Energy

Fatih Birol, chief economist of the International Energy Agency, told me the atmosphere could absorb at most another one trillion tons of CO2. It got almost 32 billion tons in 2011 alone, 3.2 percent more than the year before.

Even if emissions were to remain at the same level as last year — a highly unlikely prospect given the rapid growth of energy consumption in countries like China — the global economy, in about 30 years, would have to stop relying on fossil fuels entirely.

Most of the carbon in the ground is in the form of coal. But the world’s known reserves of oil and gas contain about one trillion tons of CO2. Applying Mr. Birol’s limit would require Saudi Arabia, Gazprom and Exxon to leave some of their reserves in the ground. They are unlikely to take kindly to this.

What’s more, Mr. Birol’s numbers may be too optimistic. Estimates by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany — reported by the Carbon Tracker Initiative in Britain — suggest that to keep the odds of exceeding the 2-degree ceiling below 20 percent, no more than 565 billion tons of CO2 can be put into the air over the next 40 years. That would require cutting the world’s total emissions by more than half, to about 14 tons a year.

Look at it this way: the world’s carbon intensity — the amount of carbon emitted into the atmosphere for each dollar of economic production — fell about 0.8 percent a year over the last decade or so. According to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, avoiding a 2-degree rise requires a decline in emissions of 5.1 percent a year — every year until 2050.

As the PricewaterhouseCoopers study suggests, it might be “too late for 2 degrees.”

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/21/the-hard-math-on-fossil-fuels/?partner=rss&emc=rss