5:23 p.m. | Updated

After its stock performance Friday, Facebook probably wishes it could unfriend its stock ticker symbol.

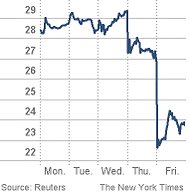

Although the stock fell to a low of $22.28, it closed at $23.71, down $3.14, or 11.7 percent. The fall resulted from a tepid earnings report by the company on Thursday.

Facebook’s stock began falling in after-hours trading Thursday, dipping below $24.

During its earnings call Thursday, David Ebersman, Facebook’s chief financial officer, said, “Obviously we’re disappointed about how the stock is traded.”

But executives seemed confident that the company would continue to raise profits and revenue with new advertising modules and a continued expansion in mobile.

The company said its revenue for the quarter climbed to $1.18 billion, from $895 million. It apparently did not instill enough confidence going forward.

Sheryl Sandberg, the company’s chief operating officer, said Facebook’s “sponsored stories” ad unit is currently generating around $1 million in revenue per day for the company, half of which comes from the mobile version of the service.

As Barron’s noted on its tech trading blog, analysts spent most Friday trying to evaluate what would happen to the stock moving forward, also updating future estimates and targets for the company.

Just like Facebook’s stock, analysts’ numbers were up and down. Victor Anthony of Topeka Capital Markets gave the stock a buy rating, with a positive $40 price target. Spencer Wang of Credit Suisse maintained a neutral rating and gave the stock a $34 price target. Anthony DiClemente of Barclays Capital cut his price target to $31 a share from $35.

Facebook was not the only company to suffer in the markets this week. Other technology companies, including Apple, Netflix and Zynga, fell after disappointing earnings. Shares in Zynga were down to $3.09, for a two-day loss of 38 percent.

Facebook went public two months ago at $38 a share, with a projected market valuation of $100 billion.

Article source: http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/07/27/facebook-stock-continues-to-fall-after-earnings-call/?partner=rss&emc=rss