Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform — Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

Economists are still searching for answers to the slow growth of the United States economy. Some are now focusing on the issue of “financialization,” the growth of the financial sector as a share of gross domestic product. Financialization is also an important factor in the growth of income inequality, which is also a culprit in slow growth. Recent research is improving our knowledge of financialization, which has yet to get the attention of policy makers.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

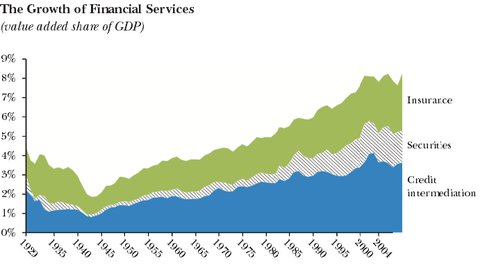

According to a new article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives by the Harvard Business School professors Robin Greenwood and David Scharfstein, financial services rose as a share of G.D.P. to 8.3 percent in 2006 from 2.8 percent in 1950 and 4.9 percent in 1980. The following table is taken from their article.

Robin Greenwood and David Scharfstein Data from the National Income and Product Accounts (1947-2009) and the National Economic Accounts (1929-47) are used to compute added value as a percentage of gross domestic product in the United States.

Robin Greenwood and David Scharfstein Data from the National Income and Product Accounts (1947-2009) and the National Economic Accounts (1929-47) are used to compute added value as a percentage of gross domestic product in the United States.

They cite research by Thomas Philippon of New York University and Ariell Reshef of the University of Virginia that compensation in the financial services industry was comparable to that in other industries until 1980. But since then, it has increased sharply and those working in financial services now make 70 percent more on average.

While all economists agree that the financial sector contributes significantly to economic growth, some now question whether that is still the case. According to Stephen G. Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi of the Bank for International Settlements, the impact of finance on economic growth is very positive in the early stages of development. But beyond a certain point it becomes negative, because the financial sector competes with other sectors for scarce resources.

Ozgur Orhangazi of Roosevelt University has found that investment in the real sector of the economy falls when financialization rises. Moreover, rising fees paid by nonfinancial corporations to financial markets have reduced internal funds available for investment, shortened their planning horizon and increased uncertainty.

Adair Turner, formerly Britain’s top financial regulator, has said, “There is no clear evidence that the growth in the scale and complexity of the financial system in the rich developed world over the last 20 to 30 years has driven increased growth or stability.”

He suggests, rather, that the financial sector’s gains have been more in the form of economic rents — basically something for nothing — than the return to greater economic value.

Another way that the financial sector leeches growth from other sectors is by attracting a rising share of the nation’s “best and brightest” workers, depriving other sectors like manufacturing of their skills.

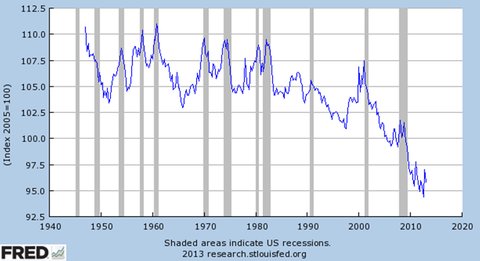

The rising share of income going to financial assets also contributes to labor’s falling share. As illustrated in the following chart from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, that share has fallen 12 percentage points since its recent peak in early 2001 and even more from its historical level from the 1950s through the 1970s.

Labor Share of Nonfarm Business Sector

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor

The falling labor share results from various factors, including globalization, technology and institutional factors like declining unionization. But according to a new report from the International Labor Organization, a United Nations agency, financialization is by far the largest contributor in developed economies (see Page 52).

The report estimates that 46 percent of labor’s falling share resulted from financialization, 19 percent from globalization, 10 percent from technological change and 25 percent from institutional factors.

This phenomenon is a major cause of rising income inequality, which itself is an important reason for inadequate growth. As the entrepreneur Nick Hanauer pointed out at a Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee hearing on June 6, the income of the middle class is critical to economic growth because of its buying power. Mr. Hanauer believes consumption is really what drives growth; business people like him invest and create jobs to take advantage of middle-class demands for goods and services, which must be supported by good-paying jobs and rising incomes.

According to research by the economists Jon Bakija, Adam Cole and Bradley T. Heim, financialization is a principal driver of the rising share of income going to the ultrawealthy – the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution.

Research by the University of Michigan sociologist Greta R. Krippner supports this position. She notes that financialization exacerbates the well-known problem of corporate ownership and control: while corporate assets are owned by shareholders, they are controlled by managers who often extract an excessive share of corporate profits for themselves.

One main source of income for financial executives is fees paid to financial asset managers, according to the Princeton economist Burton G. Malkiel. Among the best compensated of these are hedge-fund operators, who typically receive 2 percent of the assets under their control plus 20 percent of any increase, annually. (Additionally, they reap special tax benefits that are widely viewed as unjustified.)

Professor Malkiel has long been a fierce critic of actively managed funds, which seldom deliver better returns than an investor could get by simply buying low-cost index funds. Over the decade ending in 2011, index funds easily outperformed actively managed funds, in part because of the low fees on the former and high fees on the latter.

Among those pointing their fingers at financialization is David Stockman, former director of the Office of Management and Budget, who followed his government service with a long career in finance at Salomon Brothers and elsewhere. Writing in The New York Times, he recently said financialization was “corrosive” and had turned the economy into “a giant casino” where banks skim an oversize share of profits.

It’s not yet clear what public policies are appropriate to deal with the phenomenon of financialization. The important thing at this point is to be aware of it, which does not yet appear to be the case in Washington.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/11/financialization-as-a-cause-of-economic-malaise/?partner=rss&emc=rss