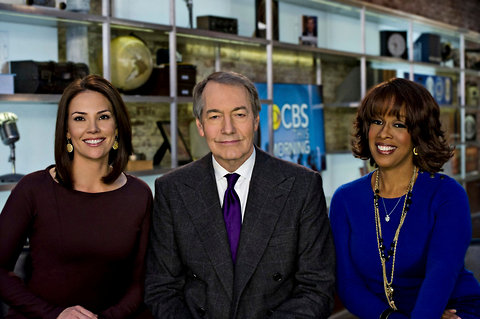

John Filo/CBS NewsErica Hill, left, Charlie Rose and Gayle King, the hosts.

John Filo/CBS NewsErica Hill, left, Charlie Rose and Gayle King, the hosts.

It is exceedingly rare for a new television newscast to be made almost entirely from scratch, as is the case with “CBS This Morning,” which will replace “The Early Show” on Monday morning.

Many of the producers and talent bookers for “CBS This Morning” are new to the network, as are two of the three anchors, Charlie Rose and Gayle King.

The anchors will sit in a brand new studio and host new segments, joined by a number of new contributors. The 7 a.m. introduction, the graphics, the musical interludes, the times of the commercial breaks — they are all new, as well.

“All due respect to the people who worked hard on ‘The Early Show,’ we really needed the new program to be a light-switch moment,” said David Rhodes, president of CBS News, who is somewhat new, too, having been on the job for 11 months.

In an attempt to overcome the network’s longtime last-place status in the mornings, “CBS This Morning” is branding itself as a more substantive alternative to NBC’s top-rated “Today” and ABC’s “Good Morning America.”

But while preparing for the change, the network was still producing the final editions of “The Early Show,” creating a TV traffic jam of sorts that Mr. Rhodes and other CBS executives had to manage.

“The Early Show” had to move out of its studio on Fifth Avenue by Jan. 1, so last week the show emanated from the electoral battlegrounds of Iowa and New Hampshire. It also borrowed the “CBS Evening News” studio and a backup control room at the CBS News headquarters in Midtown Manhattan.

Down the hall from there, Mr. Rose, Ms. King and Erica Hill, a co-anchor of “The Early Show,” rehearsed their new program as if it were live, using some of the same live shots and video clips from the campaign trail.

While watching the rehearsals, Mr. Rhodes said he “ducked out a couple of times to keep an eye on the show we actually had on television.”

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=493c667dd2f1692d166e5a3d2a971694