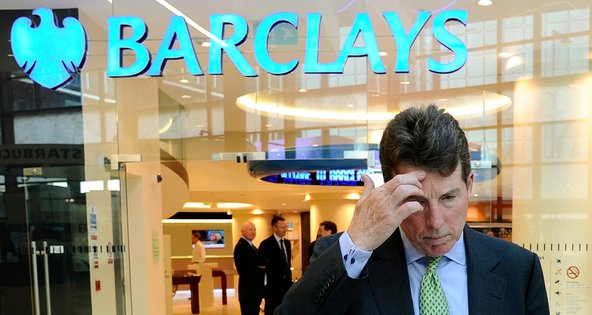

Dylan Martinez/ReutersRobert E. Diamond Jr., a former chief executive of Barclays, helped transform the British bank.

Dylan Martinez/ReutersRobert E. Diamond Jr., a former chief executive of Barclays, helped transform the British bank.

LONDON – The push to change Barclays from a predominantly British retail bank to a global financial giant over the last two decades created a culture that put profit before customers, according to a report released on Wednesday.

The independent review, which was ordered by the bank’s top management in the wake of a rate-rigging scandal last year, highlighted an “at all costs” attitude, particularly within the firm’s investment bank, that was reinforced by a bonus system that encouraged taking risks over serving clients.

“Barclays became complex to manage,” said the report, which was overseen by Anthony Salz, former head of the law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. “The culture that emerged tended to favor transactions over relationships, the short term over sustainability and financial over other business purposes.”

The conclusions represent a criticism of the strategy of a former chief executive of Barclays, Robert E. Diamond Jr., who helped transform the British firm into one of the world’s largest investment banks.

Mr. Diamond, who stepped down last year in the aftermath of the scandal involving manipulation of the London interbank offered rate, or Libor, ran the bank’s investment banking operations until taking over as chief executive in 2011.

The report released on Wednesday said the push to increase profits across the British bank’s operations led to potentially risky behavior that had a direct effect on the firm’s overall reputation.

Last year, the British bank was the first global financial institution to admit wrongdoing in the rate-rigging scandal.

Barclays agreed to a $450 million settlement with American and British authorities after some of its traders and senior managers were found to have manipulated Libor.

The British bank has also been implicated in the inappropriate sales of complex financial and insurance products to small businesses and retail customers that has led the entire British banking sector to pay out billions of dollars collectively in compensation.

The new chief executive, Antony P. Jenkins, announced a plan this year to improve the bank’s culture and profitability, including the closing of a controversial tax planning division and the elimination of 3,700 jobs, mostly in the firm’s unprofitable European retail and business banking unit.

Justin Thomas/VisualMedia, via Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesAntony P. Jenkins, chief of Barclays.

Justin Thomas/VisualMedia, via Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesAntony P. Jenkins, chief of Barclays.

Mr. Jenkins also outlined efforts to end aggressive risk-taking at Barclays. In an internal memorandum to employees, he told staff members who were unwilling to buy into the British bank’s push to rebuild its reputation to leave the bank.

Yet despite the move to improve how Barclays operates, it continues to experience cultural problems, particularly related to banker bonuses, according to the independent review released on Wednesday.

“Many senior bankers seemed still to be arguing that they deserved their precrisis levels of pay,” the report said. “A few investment bankers seemed to lose a sense of proportion and humility.”

While total employee compensation at Barclays has fallen as a result of the financial crisis, pay for the bank’s top management has remained above the industry average, the report added.

In 2011, for example, compensation for the bank’s top 70 managers was 17 percent higher than that of peers at rival banks. The disparity was a result, in part, of executives moving from the investment banking unit to less well-paid jobs in the bank’s other operations, without an adjustment in pay to reflect their new positions, according to the independent review.

“The report makes for uncomfortable reading in parts,” the bank’s chairman, David Walker, said in a statement. “We must learn from the findings.”

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/04/03/report-faults-at-all-costs-attitude-at-barclays/?partner=rss&emc=rss