The major change in the latest comprehensive revision of the national income and product accounts — known as NIPA to statistics aficionados — is to treat research and development spending as an investment, similar to the way the purchase of a new machine tool would be treated by a manufacturer, rather than as an expense. That investment is then written down over a number of years.

The result is to make the size of the economy, the gross domestic product, look bigger, and to appear to be growing faster, in years when new research spending is greater than the amount being written down from previous years. For the same reason, corporate profits also look better in those years.

A lot of money is spent on research and development. Nicole Mayerhauser, the chief of the national income and wealth division of the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which compiles the figures, said that in 2012 the total was $418 billion, about one-third of which was spent by governments. That amounted to about 2.6 percent of G.D.P.

The other major conceptual change deals with pensions. Until now, corporate and government contributions to pension plans were counted as personal income only when the contributions were made. Under the revision, the government estimates how much should have been contributed to meet the promises made to workers, and counts that amount, whether it is higher or lower than the amount actually put into the pension plan. That causes personal income to appear larger in years when pension contributions are lower than they should be.

The revised numbers also reflect some better information as new data becomes available. Ms. Mayerhauser said that it now appeared that in recent years the government might have overestimated the amount of income that went unreported by taxpayers, including the amounts of unreported tips received by restaurant employees. Revising those figures down meant that workers as a group appeared to be doing even worse than they had appeared to be doing.

And that was none too well. Before the figures were revised, it appeared that wages and salary income in 2012 amounted to 44 percent of G.D.P., the lowest at any time since 1929, which is as far back as the data goes.

But the revisions cut that to 42.6 percent, which matched the revised 2010 figure as the lowest ever.

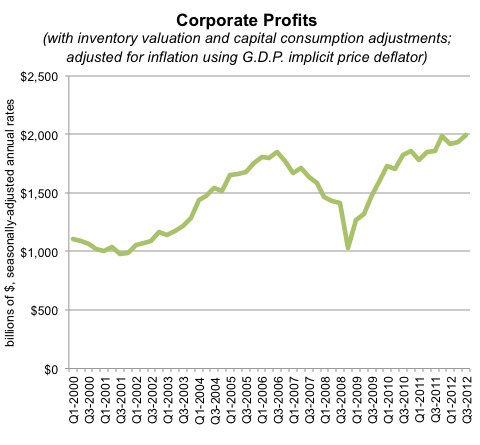

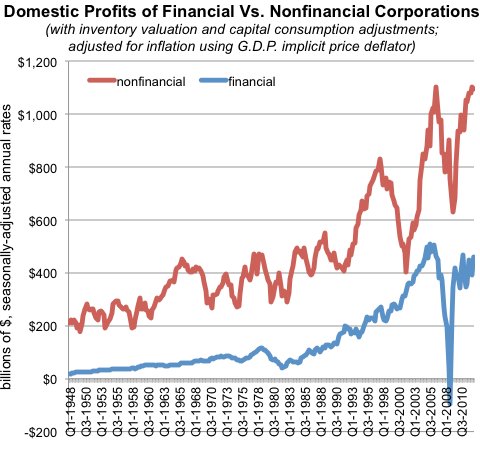

The flip side of that is that corporate profits after taxes amounted to a record 9.7 percent of G.D.P. Each of the last three years has been higher than the earlier record high, of 9.1 percent, which was set in 1929.

The charts help to demonstrate how the postrecession economy differs from the one before the downturn. In the three years from 2005 through 2007, the share of G.D.P. going to corporate profits was 1.5 percentage points lower than it was during the years 2010 through 2012. The share going to workers was 1.1 percentage points higher during the earlier years.

Corporate taxes, as a proportion of corporate profits, rose to a four-year high of 21.6 percent in 2012, but remained well below the long-term average level. Personal taxes also hit a four-year high, at 14.1 percent of personal income, but were still well below the historical average.

Floyd Norris comments on finance and the economy at nytimes.com/economix.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/10/business/economy/us-companies-thrive-as-workers-fall-behind.html?partner=rss&emc=rss