11:11 a.m. | Updated to include correct chart.

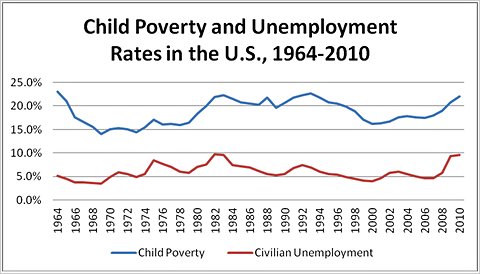

The unemployment rate ticked up to 7.6 percent while employers added about 175,000 new jobs in May, new Labor Department data showed this morning. But the economy feels very different depending on your level of educational attainment. For workers over the age of 25 who have a bachelor’s degree, the unemployment rate is 3.8 percent. For workers without a high school diploma, it is 11.1 percent.

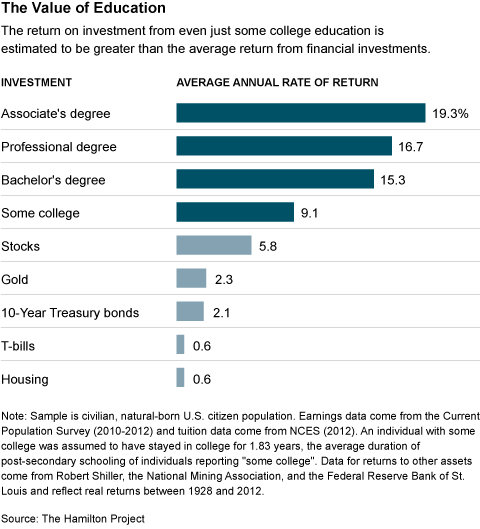

Still, in recent years, the burden of student-loan debt has raised questions about whether college is really worth it – particularly if a given person goes to college, takes on significant amounts of debt, but does not get diploma. New research from the Hamilton Project, a research group based at the Brookings Institution, says that on average, the answer is still yes.

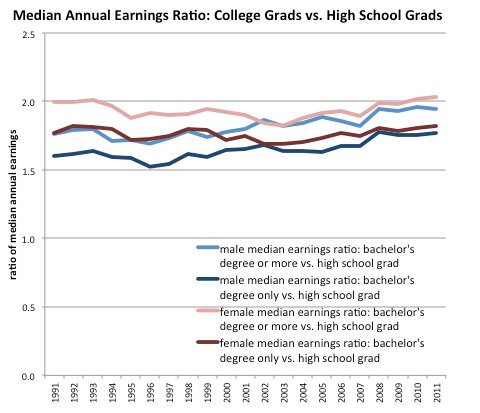

The so-called college wage premium – economists’ fancy way of saying how much more workers with a college degree are paid than other workers without one – has widened over the last three decades. Degree-holders earn more than 80 percent more than their peers with just a high school diploma, up from about 40 percent more as of the late 1970s.

But millions of students attend college without graduating, and the workplace does not reward them nearly as richly. Their unemployment rate is 6.5 percent. And while they tend to earn more than workers with just a high school diploma, they make less than workers with a full degree. (For a nuanced take on this issue, read my colleague Jason DeParle’s long-form article from December.)

“The premium for these workers has experienced little to no growth over the last 30 years, where at the median they have about 15 percent to 20 percent higher earnings,” said an analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland released last year. “Collectively, these results show that over the last three decades, the value of college has increased substantially,” with all of the gains going to those who actually complete the four-year degree.

Still, the Hamilton analysis argues that it’s better to pay something for a little post-secondary education than it is to pay nothing for none – even given the rise in college costs. Students who go to but do not graduate from college still earn about $100,000 more over the course of their lifetimes than their high school-educated peers, the authors calculate.

The rate of return on that investment in school “exceeds the historical return on practically any conventional investment, including stocks, bonds, and real estate,” find the scholars, Adam Looney and Michael Greenstone, who also is a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Granted, that student is still much, much better off with a college degree. Over a lifetime of work, on average, a college graduate would earn over $500,000 more than a worker with just a high school diploma.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/07/the-premium-from-a-college-degree/?partner=rss&emc=rss