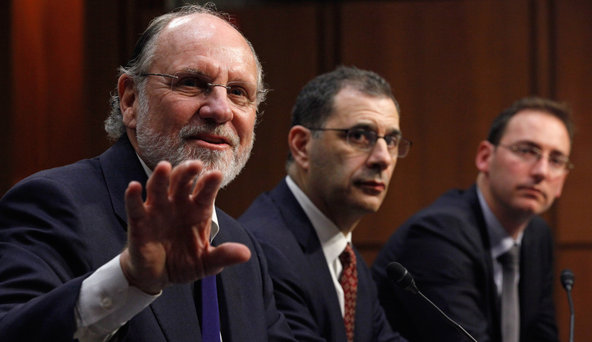

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesJon S. Corzine, the former chief of MF Global, at a House panel in 2011.

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesJon S. Corzine, the former chief of MF Global, at a House panel in 2011.

When MF Global toppled a year ago, chaos engulfed a Chicago trading floor. Customers were locked out of their accounts, later discovering that about $1 billion of their money had disappeared.

The debacle, which played out on the evening of Halloween, prompted federal authorities to immediately bear down on the brokerage firm and the broader futures trading industry.

But a year after a federal grand jury issued subpoenas and regulators vowed reforms, the largest bankruptcy since the financial crisis has begun to fade from Wall Street’s memory.

Related Links

Federal authorities have all but cleared MF Global’s top executives of criminal wrongdoing, people briefed on the matter say. The government has yet to usher in a wider overhaul of futures trading rules, save for certain piecemeal policy changes. And the profit-making exchanges that rely on brokerage firms for business still police the futures industry, presenting potential conflicts of interest.

The slowing momentum for change has provided relief for the brokerage firms that dominate the futures trading industry. The Chicago companies, which largely dodged the humbling losses that scarred Wall Street in 2008, continue to cast MF Global as a fleeting distraction rather than a permanent black eye for their business.

“We haven’t seen a dramatic change,” said Terrence A. Duffy, executive chairman of the CME Group, the giant exchange that oversaw MF Global.

But the aftermath, Mr. Duffy noted, has left some customers wary.

Farmers and ranchers traded futures contracts through MF Global to protect themselves from the price swings of their crops. While the clients have received 82 percent of their missing money, they are still owed millions of dollars.

With the prospect of a full recovery unlikely, some traders are sitting on the sidelines. Others who continue to trade are seeking added assurances that the brokerages will follow the law.

“Every conversation with clients is about safety and sanctity of customer funds,” said Mike O’Callaghan, a managing director of business development at Knight Capital’s futures business.

Futures customers — and the integrity of the industry — were dealt a further blow this summer when another firm collapsed after misusing customer money. The chief executive of the firm, the Peregrine Financial Group, attempted suicide before eventually pleading guilty to carrying out a nearly 20-year scheme to raid customers’ accounts.

The problems have taken their toll on customer confidence.

“The general tenor is fear,” said James L. Koutoulas, chief executive of Typhon Capital Management, a hedge fund client of MF Global and the head of the Commodities Customer Coalition, a group of customers fighting for the return of their missing money.

Mr. Koutoulas and other customers are eager for a reckoning. They have questioned why authorities have not taken a harder line with Jon S. Corzine, the former chief executive of MF Global. Criminal investigators have largely concluded that chaos and porous risk controls at the firm, rather than fraud, led to the disappearance of the money.

“You can’t raid customer accounts and get a slap on the wrists,” Mr. Duffy said. “There needs to be stiffer penalties.”

MF Global executives might still face legal repercussions. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the industry’s federal regulator, could level an enforcement action against Mr. Corzine, even though such an action would be weeks or months away.

“It must be frustrating to people not to have a final outcome for what may appear to be malfeasance,” said Bart Chilton, a commissioner at the agency. “But investigations take time and we need to ensure that we’ve done a thorough review.”

As authorities continue to build a regulatory case, a Congressional investigation into MF Global’s collapse is drawing to a close. The chairman of the House Financial Services Committee’s oversight panel announced Wednesday that he would release an investigative report about MF Global in the next “few weeks.” Randy Neugebauer, Republican of Texas, said the report would serve as an “autopsy of how MF Global came to its ultimate demise and what policy changes need to be made to prevent similar customer losses in the future.”

MF Global was also a topic of conversation Wednesday at an annual industry conference in Chicago. Futures firms there planned to discuss new ways to protect customer cash and restore confidence in their industry.

A regulatory effort, while incomplete, has generated new measures that aim to protect customer funds.

The CME Group, which has started a $100 million protection fund for farmer and ranchers, has stepped up its surprise audits of brokerage firms. The CME and the National Futures Association, another self-regulatory group, also championed the so-called Corzine rule, which forces top executives to approve any transfer of more than 25 percent of the funds sitting in a customer account. And last week, the trading commission voted unanimously to propose new customer protections aimed at closing loopholes.

For their part, many MF Global employees remain chastened by their firm’s collapse. Lawmakers hauled Mr. Corzine, a former senator from New Jersey, to Washington three times to testify before Congressional committees. Some MF Global employees remain unemployed while others took major pay cuts to work for the trustee unwinding the firm’s assets.

Several MF Global employees planned to gather on Thursday for drinks at a Midtown Manhattan bar, just blocks from their old firm, to commiserate on their trying year. They canceled the event after another disaster, Hurricane Sandy, left some people stranded without power.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/10/31/a-year-after-mf-globals-collapse-brokerage-firms-feel-less-pressure-for-change/?partner=rss&emc=rss