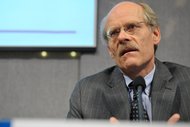

Bertil Ericson/Scanpix, via Associated PressStefan Ingves, the chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and governor of the Riksbank, the Swedish central bank.

Bertil Ericson/Scanpix, via Associated PressStefan Ingves, the chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and governor of the Riksbank, the Swedish central bank.

DAVOS, Switzerland — The head of a panel that writes the global financial rulebook answered criticism that the so-called Basel Committee has gone soft on banks, arguing that lenders need more time to adjust to new regulations because the financial crisis has lasted longer than anyone expected.

Stefan Ingves, the chairman of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, was responding to some economists and other critics who interpreted a recent decision by the committee as a signal that regulators were losing their resolve to contain risk-taking by banks.

Earlier this month, the committee decided to give banks got more time to comply with a requirement that they maintain a 30-day supply of cash other assets that are easy to sell. The rule is supposed to make banks better able to survive a financial crisis like the one that occurred after Lehman Brothers collapsed in 2008.

When regulators drafted the rule in 2010, they did not expect the crisis to last so long and for banks to still be in such a weakened state, said Mr. Ingves, who is also governor of the Riksbank, the Swedish central bank. The important thing is that there is a rule at all, he said.

World Economic Forum in Davos

View all posts

“The Basel Committee has been discussing liquidity in different forms for 30 years,” Mr. Ingves said in an interview on Friday here at the World Economic Forum. “To get to a point where a global liquidity standard has been established is an achievement in itself.”

Banks will have until 2019 to fully comply with the requirement, instead of 2015 as originally planned. The rule will still achieve its purpose of making banks safer, Mr. Ingves said.

“If there’s stress in the system, a bank shouldn’t run out of money,” Mr. Ingves said. “It should take longer than the last time before you need to go to the central bank. It’s buying insurance within the private sector itself.”

The loosening of the rule this month raised concerns that members of the Basel Committee, whose decisions serve as a benchmark for national regulators around the world, would also become more lenient on other issues as they conduct a comprehensive overhaul of banking rules.

The Basel Committee also expanded the definition of liquid assets to include even securities backed by home mortgages, one of the financial instruments that helped case the crisis. Mr. Ingves pointed out that the rules contain safeguards to ensure that banks only use high-quality mortgage-backed securities.

Following the initial outcry about changes in the rules, some other leading economists have welcomed the decision, saying it simply acknowledges the need to balance stricter oversight with the need to make sure credit keeps flowing.

There was a danger that banks in western Europe would curtail lending in eastern Europe even more severely than they already have, said Erik Berglof, chief economist of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The development bank, partly owned by the United States as well as European countries, supplies credit to the former Soviet Bloc countries as well as newly democratic countries in the Middle East.

The decision by the Basel Committee this month “was a good thing,” Mr. Berglof said in an interview. “It was particularly good for emerging markets.” In eastern Europe and many developing regions, most banks are foreign owned and dependent on their parent banks for financing.

The Basel Committee’s decisions are not binding and must be put into force by individual countries. The United States has agreed to the rules, but has come under criticism for being too slow to implement them and not sticking to the agreed blueprint. American officials point out that big banks in the country are healthier and already comply with the Basel rules that have yet to take effect.

Mr. Ingves was diplomatic when asked about the United States implementation, pointing out that the European Union is also taking longer to agree on how to apply the rules.

“They are a bit behind schedule but work is being done,” he said. “Both have said they will get this done. I have no doubt they will.”

At the World Economic Forum, the central issue is probably whether the euro zone crisis has reached a turning point. Mr. Ingves, a former official at the International Monetary Fund with decades of experiences in banking crises, was fairly optimistic.

“You never know, but it looks like it,” he said.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/01/25/amid-criticism-global-rule-maker-defends-regulatory-efforts/?partner=rss&emc=rss