Jared Bernstein is a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington and a former chief economist to Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

According to various second-quarter earnings reports, Citigroup’s profits were up 40 percent in the quarter, Bank of America’s were up 60 percent, and Goldman Sachs profits doubled.

In other news, Detroit just declared bankruptcy.

Talk about a tale of two cities.

Of course, there’s a lot going on in these different stories. Detroit, in particular, faces a complex skein of challenges, as The New York Times noted:

“…numerous factors over many years have brought Detroit to this point, including a shrunken tax base but still a huge, 139-square-mile city to maintain; overwhelming health care and pension costs; repeated efforts to manage mounting debts with still more borrowing; annual deficits in the city’s operating budget since 2008; and city services crippled by aged computer systems, poor record-keeping and widespread dysfunction.”

In Detroit, as various news reports have cited, it takes the police an hour to respond to an emergency call; the average for the nation is 11 minutes.

The city is estimated to owe as much as $18 billion to $20 billion to its creditors. For a sense of that magnitude, consider that the next largest municipal bankruptcy in United States history involved $4 billion in debt.

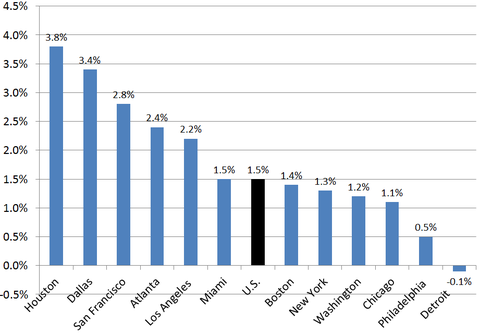

Unemployment is almost 19 percent in the city, poverty around 40 percent. The figure below shows the latest job creation numbers by city, with Detroit at the end of the graph.

Over-the-Year Change in Employment, March 2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

So in a statistical and fiscal sense, it’s a failed city, and there is a reasonable chance that a Chapter 9 bankruptcy, which in important ways is milder than the chapter of the code that applies to businesses (Chapter 11), will help it start over. But despite some sunny comments to that effect in Friday’s newspapers, there’s a lot of personal pain for retirees, pensioners, union members and city workers between here and there.

What happened, and where does the city go from here?

It’s obviously been a long way down for Detroit, and it will take dedicated urban historians to provide the full story. But a brief word about the economics.

Despite the fact that the distorted American debate claims that everybody wins, in fact, globalization creates winners and losers. That’s not at all an endorsement of protectionism. It’s saying that policy makers have to work hard, much harder than ours have, to create an environment where citizens benefit from expanded global trade not just as consumers seeking lower prices but as workers needing rising wages.

That means states and cities with industrial bases need to diversify, retrain their work forces, and look around corners to see what’s coming. I’m not saying it’s easy, and again, there will be be winners and losers. But you’ve got to try.

Second, national leaders have to recognize that there is simply no such thing as pristine “free trade.” Every country, including our own (though we tend to do so weakly), goes after export markets and tries to position itself to be internationally competitive. And some countries go further, managing their currency values to gain a price advantage and forcing excess national savings leading to large global trade imbalances. The United States has been hurt by those imbalances for decades, as our large trade deficits have exported labor demand, particularly in manufacturing, abroad. Moreover, we’ve done little to push back against these practices.

Detroit, along many other former manufacturing giants, has been hurt by the neglect of United States policy makers and the economists who advise them to rise to this challenge. Too often — and I’ve heard economists at the highest levels of power make this case — there’s an assumption that this is all the free hand of the global marketplace at work, and that we’ll rebalance our trade accounts by selling services to the rest of the world while we buy their goods.

Maybe someday that’s where things will settle, but a glance at the magnitudes — as in the figure below — should give one pause concerning that facile solution. Our trade deficits in goods are large multiples of our surpluses in services, and that’s not changing any time soon.

Source: Census Bureau

Source: Census Bureau

No, the vision that we can be a successful nation based on global finance returning profits like those above while the broad middle class falls behind, and a major city fails, is not one that most Americans would or should support.

As far as next steps for Detroit, that’s worth watching closely, as the terms of the bankruptcy are decided. The central questions will be how the pain is divided up between creditors who are fighting to resist haircuts on their loans to the city and the stakeholders noted above.

The other thing we’re about to see is a big push by conservatives to blame public unions and big government. As I’ve noted, bad governance is surely in play in Detroit, but there are lots of American cities with large public unions and active governments, and they’re not bankrupt. You simply cannot understand Detroit’s fall without considering the role of globalization and the city’s failure to diversify out of autos.

At any rate, as the tale of two cities reminds us, this is economically the best of times and the worst of times. The problem is that it’s the best of times for too small a share of us.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/19/what-went-wrong-in-detroit-and-the-road-ahead/?partner=rss&emc=rss