As I wrote on Friday, lots of young Americans are finally moving out of their parents’ basements and forming their own households now that the economy is picking up. But the bundled-household phenomenon remains large, and Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, has just shared some interesting data showing its extent.

Based on demographics and previous trends in household formation, it looks as if the country still has about 1.8 million fewer households today than it would have in a more “normal” economy, and most of that total household deficit is accounted for by the lower numbers of households formed by those in the 15-34 age group. Demographics suggest that there should be about 1.1 million more households headed by younger Americans today than there actually are.

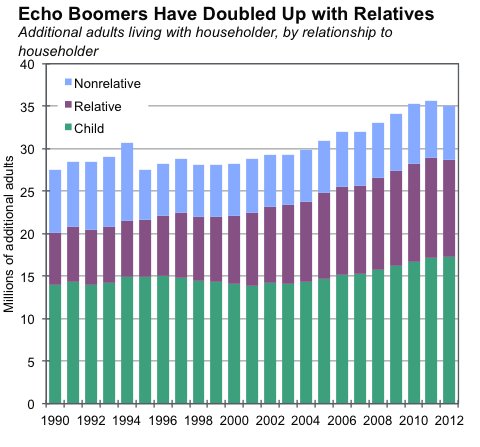

As a result, we’re still see an unusually high number of people living with parents, other relatives or friends.

This chart shows the total number of additional adults living with a home’s official householder, broken down by the relationship to the householder: nonrelative, child or other relative.

Sources: Census Bureau, IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, Moody’s Analytics.

Sources: Census Bureau, IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, Moody’s Analytics.

As you can see there are about 17.2 million adult children living in their parents’ homes this year, compared with around 15.3 million in 2007, the year the recession began.

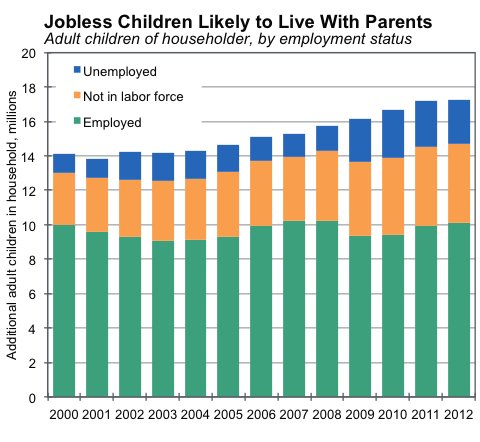

Mr. Zandi has also broken out the employment status of those adult children crashing with their folks. And the numbers show that the greatest increases are accounted for by unemployed adult children who have moved in with parents.

Sources: Census Bureau, IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, Moody’s Analytics.

Sources: Census Bureau, IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, Moody’s Analytics.

In 2007, 1.3 million unemployed adult children were living in their parents’ homes. This year, the total is about 2.5 million.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/11/12/bundled-households/?partner=rss&emc=rss