Dashboard

A weekly roundup of small-business developments.

What’s affecting me, my clients and other small-business owners this week.

Must-Reads

Christopher Mims says most data is not “big,” and businesses are wasting money pretending that it is. A. Craig Burnside, Martin Eichenbaum and Sergio Rebelo question whether the housing market upswing will last, and Rick Newman offers five reasons the housing recovery remains wobbly.

The Economy: Budget Pressures Fade

Payrolls are rising but labor productivity is decreasing. Corporate profits as a percentage of gross domestic product are at their highest levels ever (and Berkshire Hathaway’s cash hits a new high). As the red ink recedes, pressure fades for a budget deal in Washington. Cicadas invade the East Coast. A new TD Bank survey shows performance on track for small businesses, and Hispanic small-business owners have a positive outlook. A study from Wells Fargo and Gallup shows optimism among small-business owners. A new study concludes that as the economy picks up, more people with high net worths move from being employees to business owners. But 78,000 people still want to leave Earth and live on Mars.

Mother’s Day

Even presidents can be embarrassed by their mothers.

Management: Procrastinate Like a Boss

John F. Demartini says the business leaders who are best at maintaining balance in a company “will be the most loved, loving and sustainable.” Karol Krol offers suggestions for procrastinating like a boss. Joanna Warwick has the ultimate quick fix for solving any problem in your life. This is how to make the best use of small-business downtime, and here are four tips for keeping your business organized. Dennis McCafferty learned 12 management lessons from Disney U, and Matt Kemp teaches a lesson in kindness. Brad Farris is not a fan of swearing in the workplace: “For me, it turns into a kind of verbal litter, cluttering up the communication.” Bill Clinton tried to reunite Led Zeppelin.

Start-Up: The Start-Up Gap

Martin Jones explains how to start a business when you’re fully employed. Here are four things your start-up needs to attract venture capital, and here’s what Google Drive means for start-ups. This comic strip shares some simple rules for freelancers. Start-ups in Iowa lead the country in revenue, and crowdfunding is easing the cash squeeze for Arkansas start-ups. The Securities and Exchange Commission issues a call for crowdfunding suggestions to promote small-business capital formation, while a “Kickstarter for the black community” aims to close the African-American start-up gap. One venture capitalist advises against motivating start-up employees with a bonus. Neil Irwin explains why Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce would be a terrible stock.

Employees: Ridiculous and Annoying

Here are 17 ridiculous office rules companies actually enforce and 20 of the most annoying things about working in an office. And here are four reasons employees shouldn’t have set hours. A new book explains why you should have those crucial conversations with your people. Here are eight tips for retaining information technology talent. Crispin Jones discusses the benefits of a diverse workplace, and here are a few tips for building a strong team.

Entrepreneurs: The Least Favorite Question

This is how Australian entrepreneur James Fox has built a leading company, and Kathryn Minshew reveals every entrepreneur’s least favorite question. It appears that the shorter your first name, the bigger your paycheck. Neal Jenson says being able to sell anything is one of eight skills every entrepreneur should have. An Oxford University researcher says William Shakespeare was the first great “writer entrepreneur.” These teenagers are getting $100,000 each to drop out of school and start businesses.

Cash Flow: Early Warning Signs

Big manufacturers continue to put pressure on smaller suppliers. Here are a few cost-reduction strategies for small businesses. The Credit Managers’ Index drops, and Michael Monroe explains how to spot early warning signs of bad debt. This is how small businesses should leverage their debt in an unpredictable economy. Gerri Detweiler asks when you should consider bankruptcy.

Red Tape: Online Sales Tax

Adam Liptak says this has been the most business-friendly Supreme Court since World War II. The Senate approves an online sales tax bill, Senator Ted Cruz explains why he opposes it, and here’s who would be the winners and losers. John Berlau explains how the bill could tax your 401(k). This is a small-business wish list for tax reform, but Joy Taylor predicts that capital gains tax breaks are going away. A new rule means more government contracts for women.

Marketing: Pointless!

Here are a few tips for embracing green marketing. Jim Jacques says there has been a rebirth of phone answering services for businesses. Peter Hupalo explains how to make money from seminars and workshops. Gary Shouldis gives five reasons your advertising isn’t working. Dustin Heap says setting up call tracking is one of three ways to increase the return on your marketing spending. David Newman’s new book tells business owners how to improve their marketing: “Don’t be an idiot on social media.” Rob Fuggetta says this is the ultimate question you should be asking customers. Jeremy Porter explains how to take a newsroom approach to content marketing. Rhonda Campbell offers examples of blog content that drives sales, and Henry Davids believes that an average Web site is like a blunt pencil: pointless!

Local Marketing: Bleeding

Michael Borland explains how Yelp makes money. Dave Conklin offers five reasons your business needs to be doing more local search engine optimization, and a new report demonstrates how heavily mobile is used for local search. A study says daily deal sites are bleeding each other dry, and Chris Brogan wonders if local businesses deserve your money. Spike Jones says you can’t create a community because “you can’t build people.”

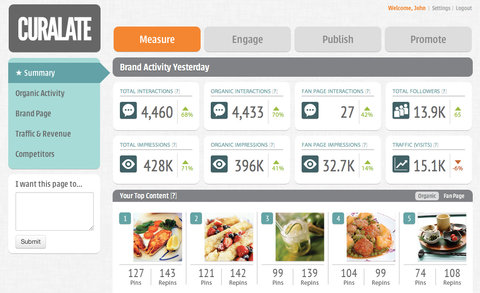

Social Media: Fans Beat Followers

A study shows small businesses find growing value in social media — and that two million Facebook fans are better than a Super Bowl ad, a celebrity endorsement or Twitter followers. Here are some tips to market your business through social networks, three tips for better social media engagement and a few hints for understanding Google Analytics. An infographic explains how social sharing improves e-mail results. Here are five quick steps for using LinkedIn to recruit and three easy ways to use YouTube to promote your business. Adam Vincenzini lists his favorite social media tools of 2013. Heidi Cohen has proof that social media drives sales, but John F. Dini says the army of social media fanatics that “go ballistic at any hint that social media isn’t the be-all, end-all and answer-from-above for every marketing need on the planet are just wrong.” This is what really happened when Facebook bought Instagram.

Around the Country: Reality TV

Small and big businesses are competing for subsidies. Small-business owners will be honored this week at a conference in Columbus, Ohio. This is how small businesses around the country have been helped by reality TV, and this is how you can turn a small business into a reality TV star. These are the best cities for college grads.

Around the World: Icebreaker

In Ireland, 80 percent of all employees spend 56 minutes of their working day on social media, and in China employees are sometimes made to crawl in public. Nearly half of all workers across Europe, the Middle East, Africa and India think that bribery and corruption are acceptable ways to survive an economic downturn, according to a new report. This is what it’s like to spend two months on an Antarctic icebreaker.

Health Care: Power Grab?

Some small business owners sue to stop the Internal Revenue Service’s health care “power grab.” Sarah Kliff wonders if the Affordable Care Act will lead to millions more part-time workers. Here are some wellness programs for small businesses. An ADP webcast this week will help small businesses understand the health care act.

Technology: Printing Guns

Microsoft has a Windows 8 do-over on the way. Here are eight Windows 8 apps for less than $25, 10 apps that will keep your business organized and 11 new iOS business apps. Coke introduces the “world’s thinnest” vending machine. Staples becomes the first major American retailer to sell 3-D printers, and a 3-D printable gun reaches 100,000 downloads. “Saturday Night Live” has some fun with Google Glass, and Marcus Wohlsen concludes that Google Glass fails to acknowledge that “walking around with a camera mounted on the side of your face at all times makes you look dorky.” Microsoft Skydrive passes 250 million users. Rob Enderle explains why Apple won’t be around as long as I.B.M. This short video will help you decide between the iPad and the Surface Pro. A new survey offers five reasons small business are turning to cloud file management. Robert Lemos suggests five ways for small businesses to increase security, but Roger Grimes warns that too many administrators will spoil your security. A study says 66 percent of small-business owners use mobile technology. Ken Mueller says there are five things small businesses need to know about customers and smartphones. And AVG Technologies shares five Mother’s Day tips for mobile moms.

Tweet of the Week

@JoeMande – What’s to stop someone from printing 3-D printers with their 3-D printer?

The Week’s Best Quote:

Anne Bezancon believes older entrepreneurs are better: “This is why, contrary to popular belief, most entrepreneurs do not create companies in their early twenties. Almost always, they have experienced real economic relationships and power dynamics, and gained an understanding of where the opportunities were, in order to figure out what problems need fixing or how something can be done better. Age is not just a data point – it signifies years spent watching, listening and learning, filing away facts and lessons, and developing the ability to recognize patterns and opportunities at the right time.”

This Week’s Question: Do you swear at the office?

Gene Marks owns the Marks Group, a Bala Cynwyd, Pa., consulting firm that helps clients with customer relationship management. You can follow him on Twitter.

Article source: http://boss.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/13/this-week-in-small-business-small-data/?partner=rss&emc=rss