Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul.

Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain, here in 2008, is venerated by many conservative Republicans in the United States.

Former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain, here in 2008, is venerated by many conservative Republicans in the United States.

Republicans have always admired former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Britain. Her 1979 election excited them enormously; Republicans viewed it as proof that their views were on the upswing and greatly increased their confidence that Ronald Reagan would be elected president in 1980 as part of a worldwide conservative trend.

Mrs. Thatcher’s stature among the American right has only increased since she was ousted by her own party in 1990. This is especially true now. Benjy Sarlin of Talking Points Memo says Mrs. Thatcher “has always been a popular figure in Republican circles across the pond, but she seems to have taken on a new relevance in recent years for the party’s leading lights.”

Mr. Sarlin cites a blog post on Mitt Romney’s Web site that draws a parallel between economic conditions in Britain in the late 1970s and those in America today. He reports that Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum also invoke Thatcher’s name frequently in their quest for the Republican presidential nomination. And last month, Sarah Palin publicly requested a meeting with Thatcher that fell through because of Mrs. Thatcher’s physical condition.

While Mrs. Thatcher is a towering figure in British political history, well deserving of admiration, the conservative legend about her time in power is at odds with the facts. In this legend, she was even more aggressive than Reagan in cutting taxes and the welfare state. But that is not true.

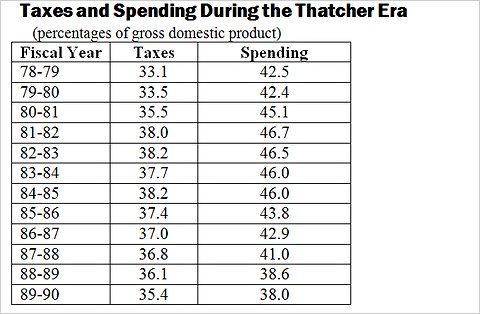

As this table shows, taxes as a share of the gross domestic product in Britain actually increased sharply during Mrs. Thatcher’s first seven years in office before falling in the later years. Even at the end, they were significantly higher than they were when she took office. Spending also rose during her first seven years before falling in Mrs. Thatcher’s later years.

Institute for Fiscal Studies

Institute for Fiscal Studies

To those familiar with Mrs. Thatcher’s tax policies, these data are not surprising. Although she cut the top personal income tax rate to 60 percent from 83 percent immediately upon taking office, the basic tax rate was only reduced to 30 percent from 33 percent. And in 1980, the 25 percent lower rate of taxation was eliminated so that 30 percent became the lowest tax rate.

More importantly, Mrs. Thatcher paid for her 1979 tax cut by nearly doubling the value-added tax to 15 percent, from 8 percent. Among those who thought Mrs. Thatcher was making a dreadful mistake was the American economist Arthur Laffer. Writing in The Wall Street Journal on Aug. 20, 1979, he excoriated her for taking with the one hand while giving with the other.

“The Thatcher budget lowers tax rates where they have little economic consequence and raises tax rates where they affect economic activity directly,” he complained.

In the 1982 forward to the British edition of his American best-seller, “Wealth and Poverty,” George Gilder was also highly critical of Mrs. Thatcher for failing to cut either taxes or spending: “The net effect of the Thatcher program has been a substantial increase in taxation on virtually all taxpayers.”

Although Mrs. Thatcher privatized many British industries and businesses that had been nationalized after World War II and sold off much of Britain’s public housing, in which the bulk of the working class lived, she did little to reduce the size of the nation’s welfare state.

In particular, Mrs. Thatcher, like all the members of her party, strongly supported the National Health Service, which provides national health insurance for every Briton.

A review of long-term spending trends in Britain by the Institute for Fiscal Studies shows that Mrs. Thatcher basically flattened a trajectory that had been rising since the war. That took a lot of political effort even though her party controlled Parliament and the prime minister of Britain has far fewer constitutional constraints than an American president. But at the end of the Thatcher era, the welfare state was still intact.

As Martin Wolf, a columnist for The Financial Times, told me, “Like all great politicians, Thatcher was a pragmatist, not an ideologue, who picked her fights carefully. She recognized that any head-on attack on the welfare state would have destroyed the party’s electability.”

Mr. Wolf said Mrs. Thatcher was far more concerned about fiscal stability and deficit reduction than lower taxes, and the idea that a debt default “would have been sensible would, to her, have been insane.”

Mrs. Thatcher, like Reagan, moved her country in a conservative direction. But Mrs. Thatcher’s fiscal accomplishments were much more modest than many of today’s Republicans think.

The lesson they should learn from her is that it is very hard to shrink the size of government even when a strong leader has complete control of the legislature, that it takes many years of arduous work to do so and that at the end of the day it won’t shrink very much.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/08/the-legend-of-margaret-thatcher-2/?partner=rss&emc=rss