CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

One of the more disappointing data points in last Friday’s jobs report was the decline in average weekly hours worked, which fell to 34.4 hours in April from 34.6 hours in March. It’s not clear what was behind the decline, which occurred in multiple industries across the private sector. (The monthly jobs report does not include the length of the workweek for government workers.)

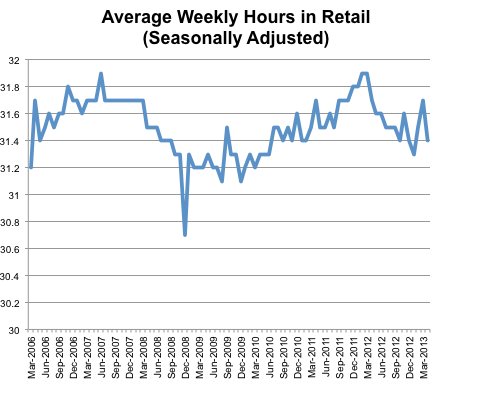

In a note to clients, Paul Ashworth, chief United States economist at Capital Economics, observed that hours in the retail sector had trended down for the last year, though the numbers had been noisy month-to-month.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

“The relatively poor performance of average hours worked in the retail sector looks odd when we consider that the gains in retail employment in the second half of last year were unusually strong,” he writes. “Normally, we would expect employment and hours worked to be going in the same direction.”

There are different ways to interpret this. One is that, as Mr. Ashworth notes, retailers might be increasingly relying on part-time help to avoid an Affordable Care Act provision that requires businesses with at least 50 full-timers to provide health insurance or pay a penalty (a requirement that kicks in next year, but is based on employment levels this year).

Blessed with more data on their customers, businesses may also be hewing more closely to the idiosyncrasies of consumer demand and staying open longer — and it’s easier to schedule a staff for longer hours of operation if individual employees are working in shorter shifts, according to Peter Cappelli, a management professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

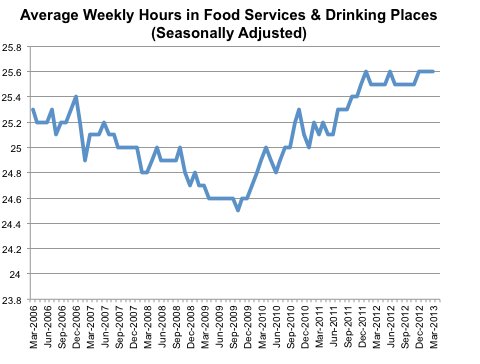

Strangely enough, food services and drinking establishments, which are among those making the most noise about the Affordable Care Act employer mandate, do not seem to have cut down their hours in recent months. That may be because workers in this sector already work relatively short hours (25.6 weekly hours on average for the latest month of data, versus 31.4 weekly hours in retail), Mr. Ashworth says.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

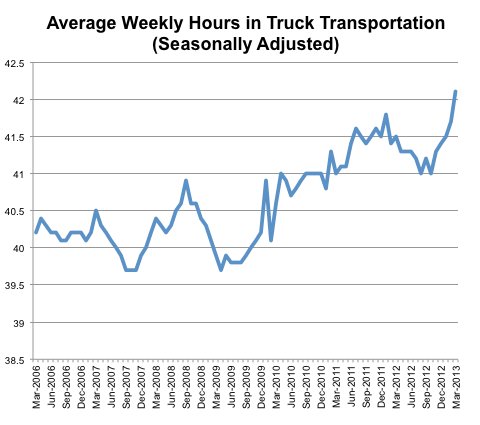

Not all sectors have been paring back hours.

Truck transportation, which has been raising compensation for its workers, has also been expanding their weekly hours:

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

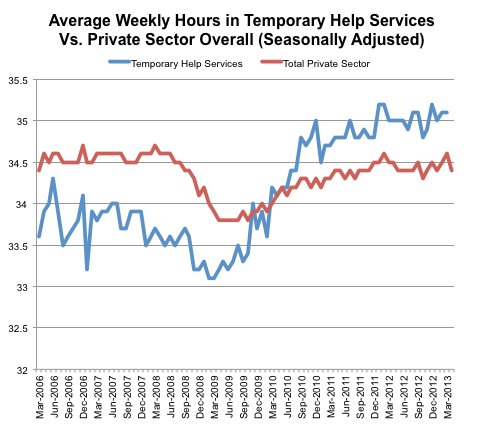

And perhaps most strikingly, hours for temp workers have also increased over a different time horizon — not over the last few months, but over the last few years. Temp workers now put in more hours than they did during the prerecession boom years, and their average workweek is now longer than that for the overall private sector. Historically, these provisional workers logged fewer hours than their permanent counterparts.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. Note that the vertical axis does not start at zero to better show the change.

These trends may speak to employers’ continued reluctance to make the commitment to permanent hires, even as demand picks up.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/07/shorter-hours-but-not-for-truckers-and-temps/?partner=rss&emc=rss