Is the Federal Reserve a driving force behind the post-recession growth in inequality? It’s a provocative idea, voiced by writers including Neil Irwin and Robert Frank.

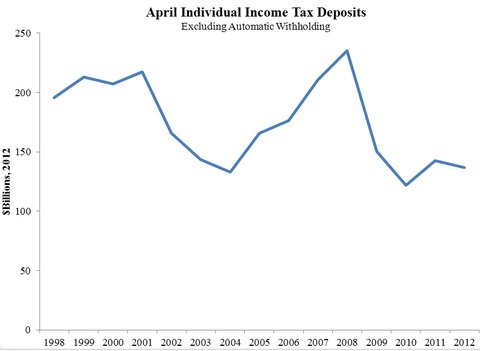

It is certainly true that inequality, in terms of both income and wealth, has widened since the recession. A study by the lauded economist Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley, found that the top 1 percent of earners have accounted for all of the income gains in the first two full years of the recovery. Their incomes have climbed about 11.2 percent. The incomes of the 99 percent have declined by about 0.4 percent.

Those patterns repeat when looking at measures of wealth, meaning the value of a family’s assets, like its house and savings account, minus the value of its debts, like mortgages and credit card balances. A recent report from the Pew Research Center found that the wealth of the richest 7 percent of households climbed about 28 percent from 2009 to 2011. For the remaining 93 percent, average wealth dropped about 4 percent.

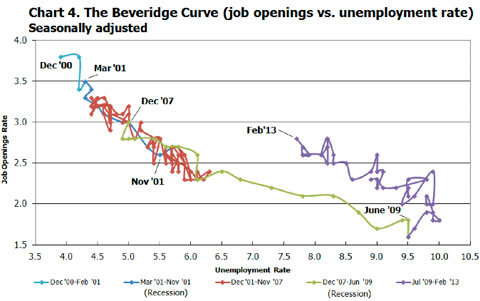

The Federal Reserve has been a major force propping up economic growth, even as Washington has started to slash the federal deficit and as droughts and debt crises abroad have taken their toll. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimated that the Fed’s aggressive policies have shaved 1.5 percentage points off the unemployment rate and have more broadly aided growth.

So if the Fed has been propping up the economy, has it also been propping up inequality? The argument would go something like this:

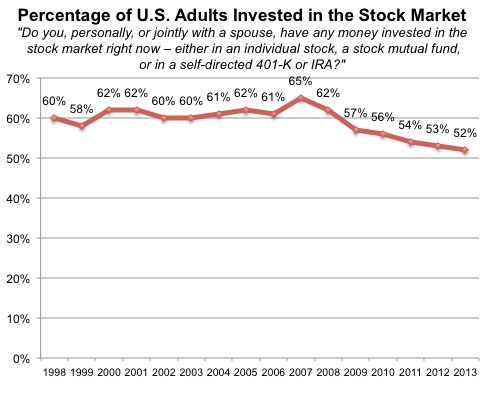

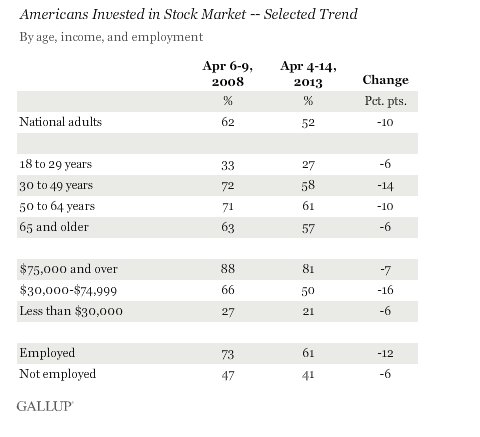

First, many financial experts consider the Fed’s policies a driving force behind the surge in the stock market. Since the depths of the crisis, the Dow Jones industrial average has more than doubled, increasing about 16 percent this year alone. Such gains have helped to lift the earnings and the net worth of the half of Americans who own stocks. But the wealthy have benefited disproportionately. According to recent research by the New York University economist Edward Wolff, the richest 10 percent of households own more than 81 percent of stocks, as measured by value.

A second factor is the rebound in the housing market, aided by the Federal Reserve’s purchase of about $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities every month. The effort has helped push down mortgage rates and make it cheaper for millions of families to buy a house or to free up some cash by refinancing. But because of tight credit standards, that windfall has mostly gone to the rich – families that meet the standards to refinance, and investors with enough cash to buy.

Looking at those two factors, there’s a strong argument that the Fed stands behind growth in inequality, particularly when it comes to wealth. But the picture is murkier when it comes to income. And experts sounded a note of caution about trying to work out the distributional effect that the central bank’s policies might be having more generally.

“I don’t think we know that much about it,” said Josh Bivens, an economist at the left-of-center Economic Policy Institute, a Washington-based research group. “It would be interesting to have a really determined academic look at the effect on all these asset groups and try to figure it out from there.”

Even if the Fed had stoked some wealth inequality through the stock and housing markets, he said, that would not be the full picture. How much did the Fed’s policies account for the housing turnaround, or the stock-price rebound? That would be hard to say. In the case of the stock markets, corporate earnings seemed the main factor, Mr. Bivens said.

Moreover, the fuller picture would need to take into account how the Federal Reserve might have eased earnings inequality by reducing unemployment. “High unemployment is much more destructive to wage growth for low-income workers than for high-income workers,” Mr. Bivens said. “The Fed might have done quite a bit to keep wages from falling even further at the low end.”

Other experts said they thought the Fed might have reduced inequality, if anything, and that one way or another it would be difficult to tell. “The effect is going to be at the margin if it is there at all,” said Joseph E. Gagnon, a former Fed official now at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. “It’s kind of a silly question to ask, though. It’s relevant to talk about international trade. It’s relevant to talk about technology. It’s relevant to talk about regulation. Monetary policy seems far down the list.”

One piece of analytical evidence that the Fed might be stoking inequality comes from the Bank of England. That central bank also undertook an aggressive round of asset purchases, and a report released last year found it helped the economy over all – but the rich much more than the poor.

Still, it described those distributional effects as unavoidable, and worth it in the long run. “Without the bank’s asset purchases, most people in the United Kingdom would have been worse off,” the report said. “Economic growth would have been lower. Unemployment would have been higher. More companies would have gone out of business. That would have had a detrimental impact on savers and pensioners along with every other group in our society.”

One way or another, it is a subject the Federal Reserve itself might have some interest in. Speaking at a conference in New York in April, Sarah Bloom Raskin, a Federal Reserve governor, posed the question of whether “inequality itself is undermining our country’s economic strength.” Her answer was an unequivocal yes. “I am persuaded that because of how hard these lower- and middle-income households were hit, the recession was worse and the recovery has been weaker,” she said.

“It is not part of the Federal Reserve’s mandate to address inequality directly,” she added, “but I want to explore these issues today because the answers may have implications for the Federal Reserve’s efforts to understand the recession and conduct policy in a way that contributes to a stronger pace of recovery.”

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/03/the-fed-and-inequality/?partner=rss&emc=rss