Site Insight

What’s wrong with this site?

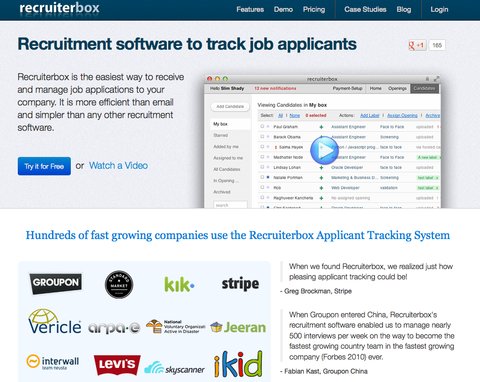

It sounds easy. Sell your product online. Design it to tempt every visitor into becoming a buyer. Add an easy-to-use self-service interface that lets customers get answers without interacting with a salesclerk. Everything seems to happen magically, and everything goes smoothly, without any issues. There may be businesses that manage to accomplish this, but rarely without a few struggles. In this post, we look at one company, Recruiterbox, and its attempt to attract customers and interact with them seemlessly.

Raj Sheth and his two partners created Recruiterbox to help companies organize their recruiting and hiring processes. An entrepreneur from India, Mr. Sheth understood that at many growing companies, the résumés, interviews and internal feedback live “all over the place,” buried in any number of in-boxes, spreadsheets and side conversations. In 2011, Recruiterbox which is based in Boston and Bangalore and has a team of 12 people, introduced a Web-based tool that automates the entire process. Hiring managers can try the service for free for a single job opening; the fee jumps to $60, $120 or $200 per month for three, six or 10 openings, respectively.

When Recruiterbox was introduced, the company stayed away from outbound marketing like e-mail or telemarketing, opting instead to rely on word-of-mouth, postings to human resources and recruitment blogs and a presence in app stores (like Google Apps). This netted their first 100 or so customers (as well as a few media mentions). Still, attracting visitors to the site was slow, and customer growth, while consistent, remained humble — in the low hundreds at the end of the first year. In 2012, the customer base grew to 500.

Mr. Sheth has found that he can generate traffic by answering media queries on HelpAReporterOut.com and by crafting frequent blog and video posts that address important H.R. issues. He also has found that including a transcript with the videos helps boost Recruiterbox’s organic search rankings on Google.

Still, revenue grew only slightly after a few months, so Mr. Sheth created a paid Google AdWords campaign. While the quality of customers that came through this channel was high, larger competitors drove up the bids for popular keywords. As a result, each click cost from $7 to $15 – making AdWords an expensive customer-acquisition channel. The Recruiterbox team kept a fixed budget on their campaign and tweaked the ads, but the cost per paying customer remained high, as much as $500.

After a year, the team began analyzing customer reactions to the sign-up process and pricing structure, which resulted in the company offering more service options. Recruiterbox now handles start-ups and smaller companies — those with fewer jobs to fill — through a self-service tool. The site has found that most of the companies that try the service end up completing the 14-day free trial and electing to continue with the monthly subscription.

But Recruiterbox wants to help larger companies, too — those looking to fill as many as 50 openings. And that’s the challenge: larger clients that want to fill 10 to 25 jobs are much more likely to require an initial service walk-through over the phone to understand how the software works. That of course is a time-consuming burden for a small company.

So the questions facing Mr. Sheth and Recruiterbox are:

Does it make sense for Recruiterbox to focus more attention on one particular customer segment?

• Would concentrating on self-service customers allow Recruiterbox to stick with its original goals and get more business?

• Is that market — companies with fewer positions to fill — large enough?

• Should Recruiterbox add more inside sales people to attract and retain larger companies or is that splintering the business focus?

Some questions for readers to think about while looking at Recruiterbox.com:

• Is it easy to understand?

• Can you tell what it’s offering within 15 seconds of landing on the site?

• Would you register without contacting customer support?

• What are your thoughts on tiered service fees?

• Do those fees represent the right value for the cost?

Next week, we’ll follow up with highlights from your comments and I’ll offer my own impressions along with Mr. Sheth’s response.

Would you like to have your business’s Web site or mobile app reviewed? This is an opportunity for companies looking for an honest (and free) appraisal of their online presence and marketing efforts.

To be considered, please tell us about your experiences — why you started your site, what works, what doesn’t and why you would like to have the site reviewed — in an e-mail to youretheboss@abesmarket.com.

Richard Demb is co-founder of Abe’s Market, an online marketplace for natural products that is based in Chicago.

Article source: http://boss.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/26/a-web-site-tries-to-keep-it-simple/?partner=rss&emc=rss