SARAH KUPFERBERG’S youthful rebellion was slightly unconventional — she wanted to invest in green companies, not the big industrials her parents had preferred. But like most novice investors, she stumbled along the way, once putting money into a company that was trying to use buoys to turn ocean waves into electricity.

“When I started investing in companies on my own, I made a lot of bad choices,” Ms. Kupferberg, an ecologist who works on issues related to energy and power. “These were companies at the leading edge of technology. They weren’t great investments.”

Today, Ms. Kupferberg, 50, said she has taken a more pragmatic approach to investing. She is no longer looking for companies at the vanguard of the green movement. Instead, she’s interested in those that are making a profit while also acting in a way that takes into account sound environmental, social and governance practices.

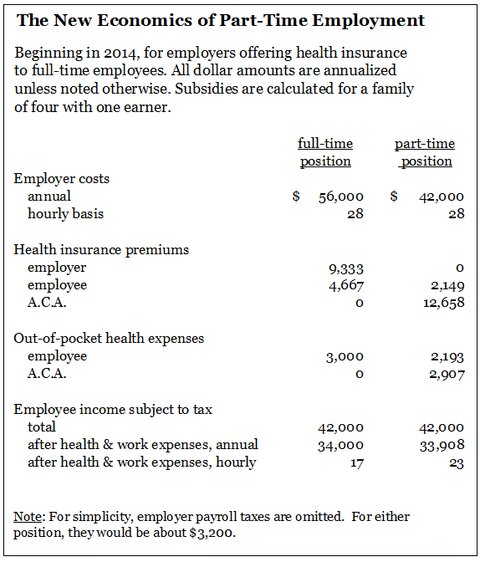

A focus on these factors — known by the shorthand E.S.G. — is a distance from the pure green investments that had less to do with returns. She has invested in Starbucks (even though she prefers to drink Peet’s Coffee) because of its policies toward its employees, like health benefits for part-time workers.

Applying an E.S.G. screen in this instance is a way to look at how companies in similar sectors compare, said Matthew W. Patsky, chief executive of Trillium Asset Management. He drew a contrast between Starbucks and McDonald’s, which does not offer health care benefits for part-time workers. Ms. Kupferberg’s view of looking for the best-behaved companies in a sector is consistent with others who are using their investment dollars to try to push companies toward more socially responsible policies. Rebekah Helzel, a retired proprietary trader for an investment bank, for example, said her focus was on eliminating “carbon-based business models” from her investment portfolio. Yet she has invested in United Parcel Service, which, of course, moves packages around the world in planes and trucks.

“They have a lot of carbon in their business model but they have done remarkable things to reduce it,” Ms. Helzel said. She mentioned their use of new technologies to reduce their carbon footprint but also the company’s oft-cited mapping technology to allow drivers to make as many right-hand turns as possible on their routes.

And many of those who embrace green have distanced themselves from the view that to be environmentally conscious is to lack investment rigor.

“This doing good while doing well thing is getting to be a bit out of date,” said Garvin Jabusch, co-founder and chief investment officer at Shelton Green Alpha Fund. “We’re looking past mere tree-huggery.”

He said E.S.G. investors needed to focus on ways to generate electricity and recycle existing products that could save resources, make a profit and be widely used.

While most E.S.G. investors are not ready to give up on tree-hugging altogether, they are taking an approach that has come a long way from simply screening out certain companies — like oil and gas, military and tobacco. They are moving toward companies that are just as focused on being profitable businesses as operating in a way that is generally better all around.

But this approach lends itself to questions — at least it did for me.

First, let’s talk returns. Are they as good as a portfolio without an E.S.G. screen? The short answer is yes. But that does not mean the returns are always spectacular.

Joseph F. Keefe, president and chief executive of Pax World Management, a mutual fund company focused on E.S.G. investments, said there was no evidence that managers focused on companies committed to improving environmental, social and governance factors were at a disadvantage.

He said that the company’s Global Environmental Markets Fund has outperformed the MSCI World Index since the fund was started in March 2008. A newer fund that invests in exchange-traded funds with the same screen has also outperformed a broader index.

“Do we have funds that are underperforming?” Mr. Keefe asked. “We sure do. We’re in the stock-picking business.”

Advisers who have been taking E.S.G. factors into consideration for years bristle at the suggestion that their process is somehow less rigorous or still based on excluding certain sectors.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/07/your-money/seeking-investments-that-are-profitable-and-a-little-bit-green.html?partner=rss&emc=rss