Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

Washington had been buzzing about the idea of minting a $1 trillion platinum coin in the event that Republicans block an increase in the debt limit (as they did in 2011), until the Treasury and the Federal Reserve rejected the idea.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

But whether or not creating a $1 trillion coin to avoid defaulting on the debt was reasonable, in accounting terms it would have been no big deal — simply a larger scale of what the Treasury and the Fed do every day.

The United States Mint, a division of the Treasury, would have had to create a $1 trillion coin of platinum — though it would not have had to contain $1 trillion of platinum — to meet the letter of the law, and the Fed would have taken ownership.

The Fed would then have credited the Treasury’s account with $1 trillion of cash that could be used to make payments authorized by the Treasury. The Fed is, in effect, the Treasury’s bank, accepting deposits and clearing payments on a daily basis.

While some people worried aloud that the creation of $1 trillion of cash would be dangerously inflationary, this is nonsense. The coin would not affect monetary policy. The Treasury and Fed constantly coordinate their actions so that tax receipts don’t reduce the money supply and Treasury payments don’t lead to an increase.

If Treasury payments threatened to raise the money supply more than the Fed would like, it would simply sell bonds from its portfolio to absorb the excess liquidity. Possessing close to $3 trillion of Treasury securities, the Fed could easily offset all the cash created by the platinum coin.

In effect, rather than the Treasury selling securities to the public to pay for spending in excess of revenues, the Fed would do so. Bonds in the Fed’s portfolio already count against the debt limit, so that is not a constraint.

Nor would the creation of a $1 trillion coin have led to higher spending. The Treasury could still spend only what has been authorized by Congress.

As a matter of accounting, the Treasury would book the $1 trillion paid by the Fed as “seigniorage.” Technically, that is the difference between the cost of creating coins and their face value. When the Fed obtains coins from the mint to distribute through the banking system, it pays the face value of the coins. According to Table 6-2 in the Analytical Perspectives volume of the 2013 budget, the mint breaks even on coinage, providing no net seigniorage to the government.

In reality, the Treasury gets a lot of revenue from seigniorage, but it shows up in a different part of the budget. Although the Fed pays the face value for coins, that is not the case with bills. The Fed pays the Treasury 5.2 cents a bill for dollar bills to 12.7 cents for $100 bills because they require more security. In 2012, the Fed paid the Treasury $747 million for currency production by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, which approximately offset its costs of operation.

The difference between the cost of bills and their face value is also seigniorage, but the profit accrues to the Fed. It also gets revenue from the Treasury on its vast holdings of Treasury securities. These securities are a byproduct of monetary policy; when the Fed buys them on the open market – it is prohibited by law from buying them directly from the Treasury – it expands the money supply, and when it sells securities the money supply shrinks.

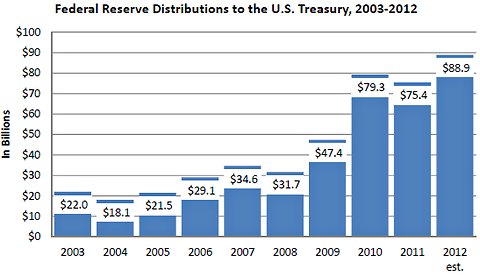

The Fed makes an enormous profit from interest paid to it by the Treasury, from seigniorage on currency and other services for which it charges banks. By law, the Fed subtracts its costs of operation and, annually, gives the rest back to the Treasury. On Jan. 10, the Fed made its annual payment to the Treasury, of $88.9 billion.

As the chart indicates, this is two or three times the revenue historically received by the Treasury from the Fed. But the Fed’s unprecedented actions, in coping with the financial crisis that began in 2008, led to a vast expansion of its portfolio, which generates much additional interest income.

Data for 2003-11 from annual report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Data for 2003-11 from annual report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

This accounting raises some interesting issues of which even economists are generally unaware. For example, although it is part of the federal government, the Fed is treated as a private bank for the purposes of calculating the gross domestic product. The data can be found in Table 6.16D of the national income and product accounts. They show that in 2011, the Fed generated a profit of $75.9 billion – 18.6 percent of all the profits generated by the financial sector of the United States economy and 5.6 percent of the total profits of all domestic industries.

Since the Fed’s profits come primarily from interest on Treasury securities, its payment to the Treasury in effect offsets much of the net interest portion of the budget. In 2013, net interest is expected to be $229 billion. But actually it is $89 billion less than that because of the Fed payment. It would make more sense, as a matter of accounting, to treat the Fed payment as an “offsetting receipt” that would lower the net interest outlay, rather than as a “miscellaneous receipt” in the budget. This has implications for calculating the burden of the national debt.

With the idea now off the table, we may never be able to assess how the coin would have played out. But most likely it would have been business as usual between the Treasury and the Fed.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/15/accounting-for-a-1-trillion-platinum-coin/?partner=rss&emc=rss