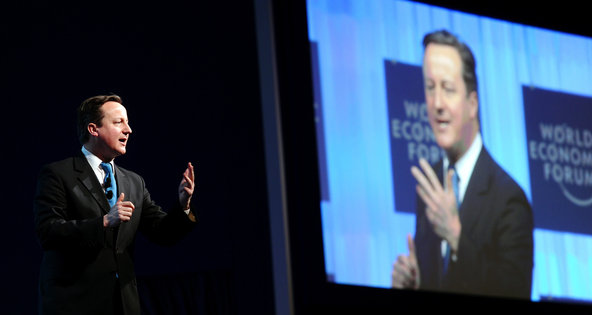

Vincenzo Pinto/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesTaking center stage at Davos, Prime Minister David Cameron of Britain appeared to take a thinly veiled swipe at the Continent.

Vincenzo Pinto/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesTaking center stage at Davos, Prime Minister David Cameron of Britain appeared to take a thinly veiled swipe at the Continent.

DAVOS, Switzerland — With concern lingering about the future of the euro zone, Prime Minister David Cameron of Britain donned his salesman’s cap on Thursday and delivered a full-throated pitch to the throngs of executives and bankers gathered here: invest in Britain instead.

Taking center stage under a hail of spotlights, Mr. Cameron tried to draw a stark distinction between the euro zone and its ongoing economic and financial troubles, and conditions in Britain’s more open economy, where the government is pushing through what he called an “unashamedly pro-business” agenda.

World Economic Forum in Davos

View all posts

“Europe’s lack of competitiveness is its Achilles heel,” he told the hundreds of entrepreneurs and policy makers gathered in the audience, and then ticked off a series of studies showing that European Union nations were losing ground on productivity. By contrast, he argued, Britain “is taking bold steps necessary to get back on track.”

His remarks appeared to be a thinly veiled swipe at the Continent less than two months after European Union leaders criticized him for refusing to sign a Europewide pact intended to help stabilize the euro zone, leading to an outburst of tension between Britain and France that has since cooled.

But for all the contrast Mr. Cameron sought to draw, Britain’s economy remains mired in a slump that is just as bad, if not slightly worse, than that of major competitors like Germany, France and the Netherlands.

Much of the talk here in recent days has been over whether the fever of Europe’s sovereign debt crisis has broken. A consensus seems to be emerging that the worst may be over, primarily because of the unexpectedly strong actions on the part of the European Central Bank to pump more money into Europe’s banking system.

Mr. Cameron, while acknowledging that the euro zone had already made “vital progress” toward resolving the crisis, painted a darker picture. “We need to be honest about the overall situation,” he said. “The crisis is still weighing down business confidence and investment.”

The troubles had already pushed the euro zone toward what could well be its second recession in three years. He argued that the region was at a “perilous moment” that menaced Britain’s own fragile economy, while neglecting to mention that his country had probably slipped into a recession of its own in the fourth quarter.

Declaring his desire to see Europe become “a success,” Mr. Cameron then rattled off a long list of reasons why the Continent might never be as competitive a marketplace for business as Britain.

Among other things, he cited data from the World Economic Forum showing that more than half of European Union member states were less competitive than a year ago. Meanwhile, he assailed a financial transaction tax favored by President Nicolas Sarkozy of France, saying the measure, which is intended to thwart financial speculation, was “madness” at a time when Europe was trying to get national economies moving again.

“In spite of its economy and unemployment challenge, we are still doing things in the E.U. to make life harder,” he said. The bloc, he added, was “imposing burdens on businesses that destroy jobs.”

Moreover, he said, the uncertainty over whether Greece might default on its debts was not helping matters. In the near term, he added, Europe must bring that crisis to an end, recapitalize the Continent’s banks and create a financial firewall big enough to keep the problems in Greece from spreading to large countries like Italy and Spain.

The Continent also needs to move toward greater economic integration, fiscal transfers and debt issuance, he argued. “Currently, it’s not that the euro zone doesn’t have all of these; it’s that it doesn’t really have any of these,” he said, to a ripple of laughter.

By contrast, he contended, Britain was overhauling its public sector pensions, reducing its debt, scrapping red tape, whittling its corporate tax regime and working to get credit flowing from banks into the economy. “My message is: Invest in Britain,” he declared.

To those who think Britain is turning its back on Europe, “nothing could be further from the truth,” he said. “It’s in our national interest to be part of the single market and we have no intention of walking away.”

Mr. Cameron then trotted out a surprise: Boris Johnson, the mayor of London, climbed to the stage to join Mr. Cameron’s call for investment, taking on the unabashed air of a circus barker. “People of Davos and investors around the world, come to London to see what we’re doing!” he called, pointing toward a video screen depicting shots of the city as it prepared to host the Olympic Games this summer.

Mr. Johnson, with his unruly straw-colored hair flying in every direction, extolled a list of products made in London, including bicycles, TV antennas and chocolate cake exported mostly to France, adding, “Let them eat cake, I always say.”

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=faec59d1a2a5c379e70ad12ffc080745