Carl Richards

Carl Richards

Carl Richards is a financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at the BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published last year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

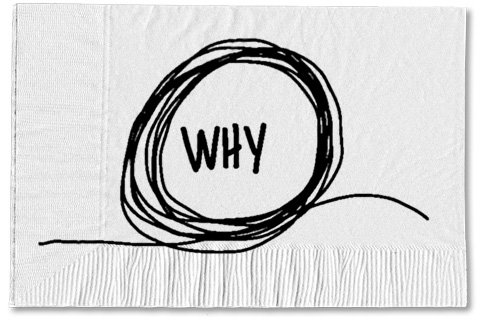

When making any financial decision, one of the most important questions we need to ask ourselves is why we are motivated to behave in a certain way. But it’s a question we tend to avoid.

Asking ourselves why we make certain money decisions can be scary because we often don’t know the answer. And admitting that we don’t know the answer can make us feel unmoored. We start to realize that we might be operating without a rudder, tossed about by whatever financial storm crosses our path.

And when we stop to question our behavior, we may not like the answer — or look for someone or something to blame. But if we’re going to improve our financial decision-making, we need to give ourselves permission to think about our motivations without judgment. To start, consider these questions:

- Why do I invest a certain way?

- Why do I spend what I spend?

- Why do I save as much (or as little) as I do?

As part of that process, I suggest:

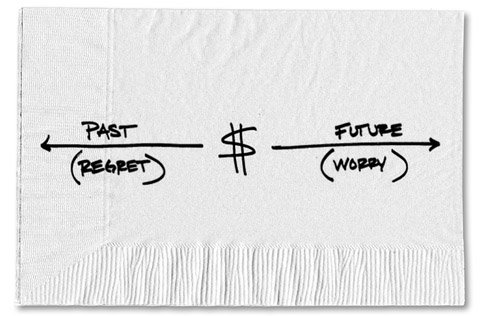

1. Letting go of the past.

Past mistakes are only useful if they help us avoid repeating the same mistake in the future. Don’t waste a valuable lesson because you’re too embarrassed to talk about it.

2. No shame, no blame.

The moment we start questioning our true motivations, we’re likely to discover that some of what we do doesn’t line up with what we say we believe. If I say that time with my children is the most important thing in my life, but I work long hours to manage a big car payment, then I’ll be forced to deal with that conflict. These conversations often involve someone else, like a spouse or children, so it’s important to give one another the space to talk about money without fear of judgment.

For instance, when my wife and I first discussed moving to Park City, Utah, we looked at a building lot. It cost more than we felt comfortable spending, so we didn’t buy it. When we finally moved a few years later, we learned that the lot was for sale again. But this time around, it was five times more expensive!

It would have been easy for each of us to blame the other for missing that opportunity. Instead, we decided to treat the experience as a lesson. The lot was still more expensive than we could have afforded at the time, a fact we could have easily forgotten if we got caught up in the blame game.

This approach would have helped another couple I know. Over the years, they made a lot of money in real estate. But the couple later lost a large amount of money in the stock market because of poor timing, not poor judgment. One partner just won’t let it go. Every time the subject of money comes up, the one partner can’t help but remind the other that they would have far more money if it weren’t for that mistake. This attitude must weigh on their relationship.

3. Focus on your plan, not society’s plan.

Questioning your motivations will also lead you to discover things about your decisions simply because you’ve never thought about them before. It’s common for adults to warn children about the dangers of peer pressure, yet adults often forget they are subject to the same pressures. So give yourself a minute or two to focus on what’s really driving your money decisions and not what society expects of you.

This type of introspection isn’t easy. I suspect it’s one of the key reasons we do dumb things with money; we’re afraid to know why we do what we do, so we don’t take the time to question our behavior. Knowing might mean needing to change something we’ve grown comfortable with.

We also live in a world that puts a premium on the notion of immediate gratification. But here’s the thing: Asking ourselves why we make a certain money decision is integral to our financial success, even if it takes a bit of time and effort to reach an answer. We just need to be brave enough to ask ourselves these hard questions.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/20/questioning-the-motives-behind-your-financial-decisions/?partner=rss&emc=rss