CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

The monthly jobs report usually gets a lot of attention, but the September numbers due on Friday are likely to absorb an outsize amount of oxygen because of the election just over a month away.

Here are some crucial details economists and analysts are likely to be looking for in the report.

One note of caution: The jobs report numbers are volatile and subject to major revisions months or even years afterward, so it’s a good idea not to read too much into any one report, Friday’s included. Last week, in fact, the Labor Department released preliminary revisions to the jobs numbers for the 12 months ended in March 2012 suggesting that the economy added 386,000 more jobs than originally believed.

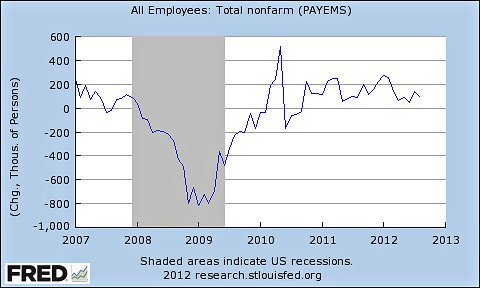

1. The number of jobs that employers added to their payrolls.

Economists are predicting job growth of 113,000, far below the economy’s long-term trend and too slow to absorb just those coming of age into the labor force.

The pace of job growth the last few months has been somewhat lackluster, with the economy adding an average of 87,000 jobs a month since April, after averaging 226,000 jobs in the first three months of this year.

It’s not clear what accounts for the slowdown; some analysts have attributed it partly to the unusually warm weather last winter, which may have caused employers to hire earlier than usual and so kept them from needing to add workers in the spring.

In any case, if we continue to have the same pace of job growth that we’ve seen so far this year (an average of 139,000 jobs monthly over the course of 2012), it will take nearly three years before the economy regains the number of jobs it had before the recession began in December 2007. We have 3.4 percent fewer jobs today than we did then, even though the number of working-age people has increased.

If we want to close the jobs gap fully — that is, add enough jobs to absorb new entrants to the labor force as well as the already unemployed — it will take more than a decade at this pace.

2. The unemployment rate.

This number refers to the unemployed as a share of Americans who want jobs and are actively looking for work. It excludes people who are out of the work force altogether and who are not applying for jobs.

It always gets a lot of attention, although economists play it down because it is based on a somewhat volatile survey. Economists are forecasting that the unemployment rate will again be 8.1 percent, reflecting the slow job growth.

3. The number of people joining or leaving the labor force.

This is based on the same noisy survey that the unemployment number comes from, and you can expect talk about it on Friday, particularly if the size of the labor force falls.

Usually in a recovery, many who were sitting on the sidelines decide to re-enter the labor force and start looking for work. In August, however, the share of Americans in the labor force fell, which is why the unemployment rate ticked down. (And that’s a bad reason for the unemployment rate to fall; we want it to fall because people who wanted jobs found them, not because people who wanted jobs stopped looking for work.)

We don’t know why the number of people in the labor force declined. It’s possible that more people than usual decided to enroll in school in August. A surprisingly large share of people who dropped out of the labor force in August did so after being employed, as opposed to unemployed.

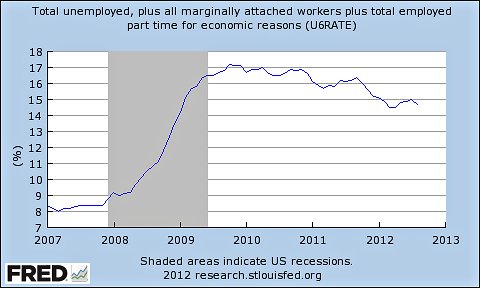

4. The broader unemployment rate.

This number includes the people who are out of work and looking for a job (the traditional unemployed), as well as two other groups of “shadow unemployed”: people who want to be working full time but can only find part-time work, and people who want to work but are no longer looking because they’ve been discouraged by their prospects. This group is sometimes referred to collectively as the “underemployed.”

This number has bounced around a bit this year, ranging from 14.5 percent to 15.1 percent. It was 14.7 percent in August. If the number goes up, you can expect to hear a lot of commentary about how the economy is worse than everybody thinks.

5. Government payrolls.

While the private sector has been adding jobs for 30 consecutive months, the public sector has been hemorrhaging workers almost every month for roughly the same period. There are fewer government workers today than there were when President Obama took office, because of job losses at the state and local levels. In August, governments at all levels shed 7,000 jobs.

Government job losses are weighing on the economy, since laid off government workers have less money to spend at private sector businesses, causing those businesses to retrench as well.

If the so-called “fiscal cliff,” which includes cutting $109 billion across the board from the federal budget, materializes at the end of this year, we can expect more government layoffs to follow. The Congressional Research Service recently synthesized a group of studies that estimated that the “sequestration” of federal funds would lead to the elimination of direct, indirect and “induced” jobs of 907,000 because of military spending cuts; 34,000 from cuts to the National Institutes of Health budget; 80,500 from cuts to education spending; and 500,000 from cuts to Medicare.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/04/what-to-look-for-in-fridays-jobs-report-2/?partner=rss&emc=rss