Ms. Olen writes that the “financial therapy movement,” for all of its flaws, “has hit on one universal truth: When it comes to money, the vast majority of us are nuts. Bonkers.” She counts some of the ways: “We don’t open our 401(k) statements. We ‘forget’ to pay our bills or file our taxes until the last minute.” Financial literacy is alarmingly low. Many of us don’t budget at all.

With a flood of financial advice available on the Internet and on television, and through books and newspapers, what’s the disconnect? Aren’t we listening?

The problem, Ms. Olen writes, is that “most of the financial advice published and dished out by the truckload is useless” — that it is simply “oblivious to the messiness of the human condition.”

What most advice fails to factor in — and what we often choose to overlook ourselves — are the costly realities of things like job loss, protracted unemployment, medical bankruptcy and high-interest debt. Even when we do save, plummeting interest rates, falling home prices and other economic events imperil our best efforts.

A former personal finance columnist for The Los Angeles Times, Ms. Olen uses as examples people who are desperate for help with managing their money. These include a real estate investor whose combination of bad luck, unemployment and poor decision-making left her in foreclosure. There is also a commercial pilot whose pension was cut and who invested in real estate that ended up plummeting in value.

Desperation, fear and insecurity can be a salesperson’s best friend. Ms. Olen learns how lucrative it is to sell financial services to the elderly, many of them terrified of outliving their savings. A 2009 AARP survey found that nearly one in 10 people over 55, or about 5.9 million Americans, had attended a free financial seminar in the last three years.

At the World MoneyShow, an annual event in Orlando, 80 percent of attendees were over 55. The author writes that “a panicked baby boomer is their best customer.”

And while Ms. Olen roundly attacks the myth that women are too emotional or ignorant to handle money well, she notes that they often lack confidence in their money management skills. Women also live longer than men and earn less. Saving more money, as women are exhorted to do, isn’t the issue, Ms. Olen says: “How they should do this with a lesser income that’s expected to do more goes unsaid.”

Unusual, and refreshing, is her inclusion of so many women’s voices throughout the book, such as the writer Jane Bryant Quinn; the financial adviser Manisha Thakor, the labor economist Teresa Ghilarducci, and Elizabeth Warren, recently elected to the Senate from Massachusetts.

One woman who comes in for some scathing treatment is the best-selling financial adviser Suze Orman, whom Ms. Olen criticizes as offering “financial platitudes” and making huge amounts of money by telling others to be frugal. Ms. Olen writes that “Orman’s supposed wisdom often contradicts itself,” and that her affiliations with companies like FICO and Lending Tree raise questions about the impartiality of her advice.

She criticizes many other financial gurus, saying they have provided unhelpful or confusing advice. These include Robert Kiyosaki, who in “Rich Dad, Poor Dad” referred to investments that “may have returns of 100 percent to infinity,” and the television personality Jim Cramer, whom the author describes as “a sweating and howling man” and who once declared that “Bear Stearns is not in trouble!” shortly before it collapsed.

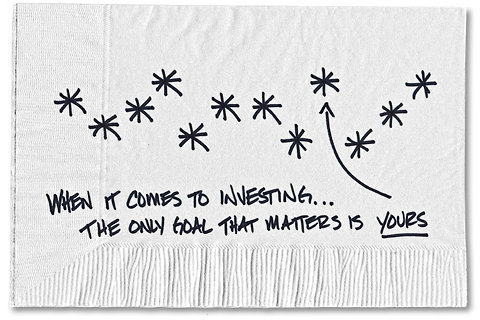

Even good investing advice is often unhelpful, Ms. Olen says, because millions of Americans have saved so little money. For people who do have enough money to invest, the ability of financial services firms to charge high fees, unchallenged, is abetted by low rates of financial literacy. Many investors are unwilling to question glowing promises of double-digit returns or to read carefully the small print on a mutual fund statement. Our overly optimistic expectations of investment performance too often meet the reality of little professional oversight for all but the wealthiest.

While we know intellectually that we need to save and invest for our future, our ability to do so varies enormously, Ms. Olen points out.

“Between 1979 and 2007, the average after-tax income for the top 1 percent of earners in the economy soared by 281 percent,” she writes. “The top 20 percent would see their incomes increase by 95 percent. The middle fifth? A mere 25 percent.”

THE solutions offered by the personal finance world have been unrealistic, she says, contending that “the increasing problem Americans were having keeping up financially was not viewed as a social justice problem, but as a knowledge and smarts problem that could be solved on an individual basis, one investor at a time.”

She’s clear-eyed about the challenge of saving and investing when you simply have nothing to work with, and when decisions about spending are a daily quandary as prices rise and wages remain stagnant or fall.

Ms. Olen describes playing Spent, an online role-playing game in which players are asked to make decisions while earning minimum wages, like those often found in retailing, the nation’s largest source of new jobs. The goal is to get to the next pay cycle without debt.

“I’ve played Spent dozens of times,” she writes, “and I’ve never, ever made it to the end of the month.”

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/30/business/pound-foolish-eyes-problems-of-personal-finance-advice.html?partner=rss&emc=rss