Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

The Federal Reserve Board last week released the latest data on national wealth. Economists were gratified to see that the net worth of Americans is very nearly back — less of a tenth of 1 percent — to where it was before the 2007 crash. At the end of that year and at the end of 2012, net national wealth was just over $66.1 trillion. The rising stock and housing markets are the primary reasons, but so is the decline in debt, which is down $822 billion since 2007.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

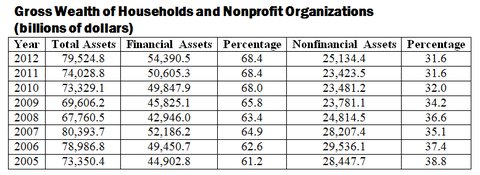

This generally good news, however, masks the fact that the benefits of rising wealth have not been equally shared. As one can see in the table, which is based on gross assets, there has been a significant change in the composition of assets. Much more is now held in the form of such financial assets as stocks and bonds and much less in nonfinancial assets, principally home equity.

Federal Reserve Board

Federal Reserve Board

Obviously, this has important distributional implications because the average middle-class family has the bulk of its wealth tied up in its home. According to the Fed, the gross value of household real estate is $5 trillion below its precrash peak: $17.7 trillion in 2012 compared with $22.7 trillion in 2006.

Depressingly, the gross value of household real estate is up only about $1.4 trillion over the last year despite a 7.3 percent increase in home prices, according to the widely followed Case-Shiller Index. The nation will need to do that well annually for another three years before beleaguered homeowners are back to where they were in 2006 in terms of housing wealth.

Obviously, those lucky or smart enough to be in the stock market have reaped the bulk of wealth gains. These have gone overwhelmingly to the wealthy. According to the New York University economist Edward N. Wolff, corporate stock constitutes just 3.1 percent of the net wealth of the middle class (defined as the middle three wealth quintiles), excluding pension accounts, with two-thirds of their wealth in home equity. (Raw data are from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances.)

But for the ultrawealthy (defined as the top 1 percent), home equity accounts for only 9.4 percent of their wealth, with stocks accounting for 25.4 percent. The not-quite-rich (defined as the next 19 percent of households below the top 1 percent) are also heavily invested in stocks, which constitute 14.9 percent of their wealth, with 30.1 percent in home equity.

These data have important macroeconomic consequences, because household wealth and its composition affect people’s work, saving and consumption.

According to a generally accepted rule of thumb, consumers spend 3 to 5 cents from every $1 increase in wealth. Thus the $10 trillion decline in household net wealth from 2007 to 2009 took $300 billion to $500 billion in annual spending out of the economy, enough to reduce the gross domestic product by 2.1 percent to 3.5 percent in 2008 and 2009 – more than sufficient to account for the length and depth of the recession.

But recent research suggests that the negative impact of declining wealth may even be greater because people react differently to changes in housing wealth than they do to changes in financial wealth. They also react differently to declines in wealth than they do to increases in wealth.

The latest research – by the economists Karl E. Case, John M. Quigley and Robert J. Shiller – shows a $1 decline in housing wealth reduces consumption by 10 cents per year, whereas a $1 increase in housing wealth raises spending just 3.2 cents. This suggests that homeowners will spend $500 billion less this year than they would if home prices were at their 2006 level.

By contrast, changes in stock-market wealth have a much smaller effect on spending. Consumption rises or falls about 2.5 cents for each $1 change in stock market wealth. Therefore, the $4 trillion increase in financial wealth from 2011 to 2012 will add only about $100 billion to spending this year.

The decline in wealth among those nearing retirement has been especially stressful, with many forced to work years longer than they planned. At the same time, there are fewer job opportunities for those in their 50s and early 60s. This has forced many to burn through savings put aside for retirement faster than they planned, while others will need to save more to compensate for declines in asset values, which will reduce their ability spend even if the housing and stock markets continue to rise.

The decline in wealth may have long-lasting consequences as well, by reducing bequests to the next generation. Given that younger workers are already having a harder time saving and investing than their parents’ generation, in part because of crushing student debts, the depletion of their parents’ wealth could leave many with no inheritances that might have helped fill the gap.

While a rising stock market is good news, its impact is limited because few Americans own much stock. Those who have been lucky enough to benefit are increasing their spending and thus raising economic growth, but there aren’t enough of them. Most Americans need the housing market to rise considerably more before their finances are restored. That will be several more years, even if current positive trends continue.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/12/wealth-spending-and-the-economy/?partner=rss&emc=rss