Nick Bilton/The New York Times

Nick Bilton/The New York Times

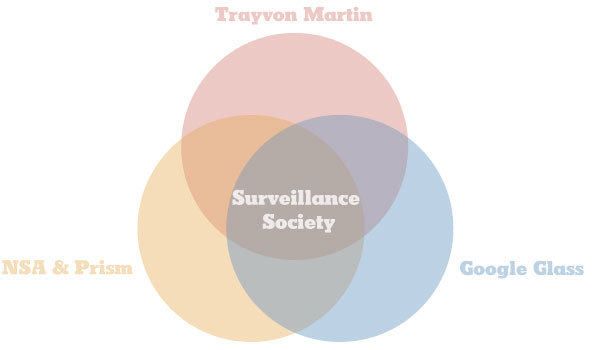

Here are three topics much in the news these days: Prism, the surveillance program of the national security agency; the death of Trayvon Martin; and Google Glass and the rise of wearable computers that record everything.

Although these might not seem connected, they are part of a growing move for, or against, a surveillance society.

On one side of this issue we have people declaring that too much surveillance, especially in the form of wearable cameras and computers, is detrimental and leaves people without any privacy in public. On the other side there are people who argue that a society with cameras everywhere will make the world safer and hold criminals more accountable for their actions.

But it leaves us with this one very important question: Do we want to live in a surveillance society that might ensure justice for all, yet privacy for none?

In the case of Mr. Martin, an unarmed black teenager who was fatally shot by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch volunteer, the most crucial evidence about how an altercation between the two began — one that ultimately led to Mr. Martin’s death — came down to Mr. Zimmerman’s word.

As the trial showed, eyewitness accounts all differed. One neighbor who was closest to the altercation saw a “lighter-skinned” man on the bottom during a fight that ensued. Two other neighbors believed that Mr. Zimmerman was on top during the fight. One said she saw the man on top walk away after the fight.

Clearly the memory of one or all of those neighbors had been spoiled by time, confusion and adrenaline. But if one of those witnesses — including Mr. Martin or Mr. Zimmerman — had been wearing Google Glass or another type of personal recording device, the facts of that night might have been much clearer.

“Whenever something mysterious happens we ask: ‘Why can’t we hit rewind? Why can’t we go to the database?’” said Jay Stanley, a senior policy analyst with the American Civil Liberties Union in Washington. “We want to follow the data trail and know everything that we need to know. The big question is: Who is going to be in control of that recording and data?”

Prism, the highly secretive government program that was brought to light last month by a government whistleblower, is an example of a much larger scale of recording and data. President Obama has defended the government’s spying programs, saying they help in the fight against terrorists and ensure that Americans stay safe.

But critics say it goes too far. Representative James Sensenbrenner, the longtime Republican lawmaker from Wisconsin, compared today’s government surveillance to “Big Brother” from the Geroge Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

Michael Shelden, author of “Orwell: The Authorized Biography,” told NPR earlier this month that today’s surveillance society is just like the book.

Orwell, Mr. Shelden said, “could see that war and defeating an enemy could be used as a reason for increasing political surveillance.” He added, “You were fighting a never-ending war that gave you a never-ending excuse for looking into people’s lives.”

Data collection and video surveillance are only going to continue to grow as technology seeps into more areas of our culture, either strapped to our bodies as wearable computers or hovering over cities as inexpensive drones that monitor people from the sky.

So what can people do? Those who want to protect people’s civil liberties say more cameras is the only real check and balance left.

“In the hands of an individual, the video camera can be a very empowering thing,” Mr. Stanley said. “When it’s employed by the government to watch over the citizens, it has the opposite effect.”

Article source: http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/16/the-pros-and-cons-of-a-surveillance-society/?partner=rss&emc=rss