Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

It’s the season of holiday cocktail parties, demanding intelligent chit-chat over Chardonnay. In such data-free environments it is always safe to say, “Medicare spending is out of control!” Wise heads will nod, because it is a credo with wide currency.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

After all, as I explained in my previous post, traditional Medicare, which still attracts about 75 percent of all Medicare beneficiaries, affords its enrollees free choice of providers and therapy. In the jargon of health-policy wonks, it is “unmanaged.” Thus, it would not be surprising if unmanaged Medicare spending were, indeed, out of control.

But some caution is in order. A really wise guy in the crowd, one familiar with relevant data, might challenge you with: “Oh, really? In what sense is Medicare spending out of control?”

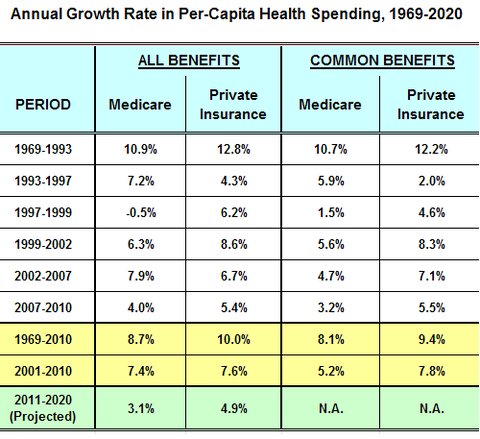

That query might have been prompted by the following data.

Kaiser Family Foundation

Kaiser Family Foundation

These data, most of which have been published by the Office of the Actuary, Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services, of the Department of Health and Human Services (see Table 16), show that in most periods Medicare spending per Medicare beneficiary has risen more slowly than per-capita spending under private health insurance.

The exceptions are the period 1993-97, when private managed-care plans appeared to be able to hold down their outlays on health care better than did Medicare, and 2002-7, because there was a jump in spending as Medicare began, in 2006, to cover prescription drugs under the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003.

So anyone claiming that “Medicare spending is out of control” can fairly be asked to explain on what data that assertion is based. The responses might be interesting.

Two objections might be raised to my interpretation of the data.

First, the benefit package of Medicare differs from those of private health insurers at any point in time. Worse still, benefit packages have varied over time in both sectors. This makes such comparisons difficult.

During the 1990s, for example, when Medicare’s benefit package remained relatively stable, those in employment-based private insurance expanded significantly, especially in their coverage of prescription drugs, which soon became the fastest-growing component of health spending among private insurers. In those years, Medicare did not cover prescription drugs.

Similarly, during the last decade or so, many private health-insurance policies have incorporated more and more cost-sharing by patients at point of service.

To control as best they can for differences in benefit packages, the centers’ actuaries also calculate comparative growth rates over longer periods of time for only those benefits that have been covered by both Medicare and private insurance plans. The two right-most columns in the exhibit present those calculations.

These columns, too, hardly support the assertion that Medicare spending is out of control. Relative to private insurance, the opposite appears to be the case, with the exceptions noted above.

A second objection to my interpretation of the data might be that Medicare is what economists call a “monopsonist,” a single buyer in a market with many sellers. In such a market, the monopsonistic buyer has considerable power over the level and the growth rate of prices over time.

With very few exceptions, Medicare pays prices to providers of health care below those paid by private insurers, which individually negotiate prices with each provider. I have already described Medicare’s pricing practices in several earlier posts and pricing practices in the private insurance market as well.

Critics of Medicare — notably private health insurers — contend that the higher prices for health care paid by private insurers can be explained by a “cost shift” from government, notably Medicare, to private payers. This view reflects the idea that the providers of health care are to be “reimbursed” for whatever costs they incur in treating patients, rather than budgeting backward from whatever revenue they are “paid,” like other sellers (e.g., hotels or airlines), which can charge different prices to different customers for the same thing.

The cost-shift hypothesis appears to have widespread, intuitive appeal, especially among employers and their agents, private insurers. Economists, this one included, do not find it persuasive, as can be seen in this review of the economics literature on the cost-shift hypothesis and this summary. Economists believe that what is denounced as “cost shifting” in health care is mainly just good old-fashioned, profit-maximizing price discrimination based on differential market power, which is not to be confused with cost shifting.

The economists’ skepticism aside, I would caution the proponents of the cost-shift hypothesis to think twice before injecting it into the health policy debate.

If private insurers cannot resist price increases for health care in response to lower Medicare fees, then presumably they cannot resist price increases in response to other factors — e.g., the medical arms race, for which hospitals are known, or the “edifice complex” to which many hospitals (and, it should be noted, universities) have succumbed.

In a nutshell, reliance on the cost-shift hypothesis to explain the data in the exhibit above strikes me as an open admission by private insurers that they cannot offer effective countervailing market power vis-à-vis the providers of health care.

It would imply that health-spending growth in the private sector can be constrained only through substantial reductions in the use of health care — either through higher cost-sharing by patients or other managed-care techniques — reductions that would be all the deeper because they would be partly offset by price increases.

So I would remind the cost-shift aficionados of this Roman adage: bis cogitare semper memento (remember to always think twice).

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/21/medicare-spending-isnt-out-of-control/?partner=rss&emc=rss