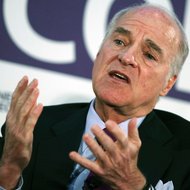

Keith Bedford/ReutersHamilton E. James, president of Blackstone Group.

Keith Bedford/ReutersHamilton E. James, president of Blackstone Group.

The private equity giants Blackstone Group and Kohlberg Kravis Roberts are longtime rivals that compete for multibillion-dollar deals. But during last decade’s buyout boom, according to newly released e-mails in a civil lawsuit accusing them of collusion, the two firms appeared to be on much cozier terms.

In September 2006, for instance, Blackstone and K.K.R. were both circling the technology giant Freescale Semiconductor. After a Blackstone group outbid a K.K.R. consortium to buy Freescale for nearly $18 billion, Hamilton E. James, the president of Blackstone, e-mailed his colleagues about Henry Kravis, the billionaire co-founder of Blackstone’s rival.

“Henry Kravis just called to say congratulations and that they were standing down because he had told me before they would not jump a signed deal of ours,” Mr. James wrote.

Related Links

Two days later, Mr. James sent an e-mail to Mr. Kravis’s cousin and co-founder, George R. Roberts. “We would much rather work with you guys than against you,” Mr. James wrote. “Together we can be unstoppable but in opposition we can cost each other a lot of money.”

“Agreed,” responded Mr. Roberts.

Shannon Stapleton/ReutersHenry Kravis of the equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts.

Shannon Stapleton/ReutersHenry Kravis of the equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts.

The e-mails are part of a court filing Wednesday in an antitrust civil lawsuit brought against 11 of the world’s largest private equity firms that accuses them of colluding to drive down the prices of more than two dozen takeovers of publicly traded companies. Plaintiffs in the case, which was filed in Federal District Court in Boston in 2007, are former shareholders of the acquired businesses.

Much of the 207-page lawsuit had been heavily redacted, but The New York Times brought a motion in August to make the all of the complaint public. A judge ordered the private equity defendants to file an unsealed version of the court papers, leading to the new filing on Wednesday.

“These e-mails are strong signals of anticompetitive behavior,” said Darren Bush, an antitrust law professor at the University of Houston. “It is always highly problematic when you have such freewheeling discussions between competitors.”

The private equity firms scoff at the idea that their conduct was improper. A Blackstone spokesman, Peter Rose, said that the Freescale deal was competitive and the firm paid a generous price for the company. “Blackstone and K.K.R. have since competed intensely many times and have completed only a single deal together in the past six years,” said Mr. Rose.

A spokeswoman for K.K.R., Kristi Huller, said the plaintiffs “make the preposterous claim that the entire private equity industry came together under a master plan to decide which firms would be permitted to acquire any particular public company.”

The evidence in the case comes as the private equity firms and their business practices remain a focus of the presidential race. The Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney founded Bain Capital, which is a defendant in the lawsuit. Mr. Romney has made his Bain tenure a cornerstone of his campaign to demonstrate his leadership and private sector experience. At the same time, President Obama has used Bain to attack Mr. Romney, accusing the firm of firing employees at its acquired companies and sending jobs overseas.

While top executives at Bain Capital are mentioned in some of the more revealing e-mail exchanges, Mr. Romney does not appear in the newly unsealed documents.

“This industrywide case involves matters that occurred well after Mitt Romney left Bain Capital in 1999,” said Michele Davis, a spokeswoman for the campaign. “He had no role in investment decisions or operations after that date.”

But the shareholders’ lawyers in the case said that the allegations of collusion reflected on Mr. Romney because he reaped millions of dollars from profits that may have been illegally inflated by underpriced acquisitions.

Mr. Romney’s financial disclosures “list all the funds that profited from these deals, so he clearly profited,” said a lawyer representing the plaintiffs who supports Mr. Obama.

The lawsuit’s allegations date to the years leading up to the financial crisis. Private equity firms, armed with billions of dollars from state pensions and sovereign wealth funds seeking returns on investments, were buying ever-larger companies. And flush banks like JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup backed the firms with billions of dollars of loans to finance their acquisitions.

Led by the likes of Bain, Carlyle Group and Apollo Management Group, the private equity firms made headlines with record takeovers of a number of the nation’s iconic companies. The country’s largest casino operator (Caesars Entertainment), hospital chain (HCA), and lodging company (Hilton Hotels) all fell into the hands of private equity firms.

An unusual feature of these megadeals is at the heart of the lawsuit: The private equity firms are said to have teamed up to do them.

As purchase prices reached into the tens of billions of dollars, the firms pooled their money together to make the acquisitions. The private equity industry has said that the consortiums, or club deals, allowed the firms to spread the risk of owning such a large company. In addition, the firms said that by working together they could bring complementary skills in operating the companies once they acquired them.

The media analysis firm Nielsen, for example, was taken over for $11.4 billion by a group of six different buyout firms. All of the collaboration meant that there were fewer potential buyers for these companies.

The flood of private equity takeovers continued right up until the credit crisis struck, forcing banks to close their lending spigot and ending the buyout boom. The $32 billion acquisition of the Texas power utility TXU, the largest leveraged buyout in history, was consummated on Oct. 10, 2007, the day after the Dow Jones industrial average hit a record high.

While the private equity firms characterized the period from 2003 to 2007 as a time of big deal-making and collaboration, the Massachusetts lawsuit contends that something far more sinister was at work.

Calling the period “the conspiratorial era,” the lawsuit depicts a secret pact between the firms that divided up the big deals among themselves and artificially — and illegally — kept their prices low. There was a “you don’t bid on my deal, I won’t bid on yours” understanding between the firms, according to the lawsuit.

“These L.B.O.’s and transactions were not separate, isolated events; rather, they were interconnected deals that defendants carefully planned, coordinated and tracked as part of their ongoing conspiracy,” said the complaint.

These efforts drove down buyout prices and deprived the company’s shareholders of billions of dollars, the lawsuit said. Shareholders filed the complaint in 2007 after the Justice Department’s antitrust division began investigation possible collusion and bid-rigging. The government has not brought any charges.

The private equity firms insist that there was healthy competition for deals during last decade’s mergers and acquisitions boom.

Several deals cited in the complaint did feature bidding wars that drove up the purchase prices. In court papers, the private equity firms have said that the lawsuit is nothing more than “a far-fetched theory” that describes routine merger activity and calls it anticompetitive.

Yet there was nothing routine about the flurry of merger activity during the buyout boom. In early 2006, Bain, K.K.R., and Merrill Lynch teamed up with HCA management to pay $32.1 billion for the hospital chain. At the time, it was the largest leveraged buyout and turned out to be a hugely profitable deal.

K.K.R. expressly asked its competitors to “step down on HCA” and not bid on the company, according to an e-mail that was unsealed and written by Daniel Akerson, then a partner at Carlyle and now the chief executive of General Motors. The complaint includes several other e-mails explaining the lack of competition in the bidding for HCA.

Two colleagues at the private equity firm TPG e-mailed each other about the firm’s reasons for deciding to not compete for HCA, according to the lawsuit.

“All we can do is do [u]nto others as we want them to do unto us,” Jonathan Coslet, a TPG executive, wrote. “It will pay off in the long run even though it feels bad in the short run.”

A TPG spokesman denied the allegations in the lawsuit and said that it never colluded to suppress deal prices.

Mr. Bush, the University of Houston antitrust law professor, said that such an exchange between the TPG executives should raise eyebrows among government antitrust regulators as classic anticompetitive conduct.

“This sounds like mutual back-scratching,” said Mr. Bush. “I’ll scratch your back by not bidding on this deal, and you’ll scratch mine by not bidding on the next.”

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/10/10/e-mails-back-lawsuits-claim-that-equity-firms-colluded-on-big-deals/?partner=rss&emc=rss