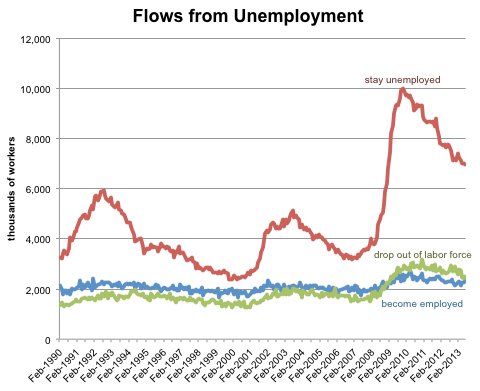

Friday’s jobs report was good, but it’s worth remembering that people already unemployed are still having a terrible time finding work. This is particularly evident from the Labor Department’s flows data, which track the labor force status of individuals from one month to the next. Here’s a chart showing the flows for unemployed workers — that is, if a worker was unemployed last month, what is his or her labor status this month?

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. The lines show worker flows from unemployment last month into each of the following statuses in the current month: unemployment, not in labor force, employment.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics. The lines show worker flows from unemployment last month into each of the following statuses in the current month: unemployment, not in labor force, employment.

As you can see, the most likely outcome for someone unemployed in May was to continue being unemployed in June. The second-most-likely outcome was to drop out of the labor force entirely — that is, stop looking for work. (That’s part of the reason that today’s labor force participation rate is so low, although the biggest flow into the “not in labor force” category still comes from people who are leaving jobs rather than giving up a fruitless job hunt.)

Finally, the third-most-likely outcome was to find a job. Over all, fewer than one in five people who were unemployed in May were employed in June.

Unemployed workers have been more likely to flow out of the labor force than into employment for almost the entire period beginning around December 2008 to the present. This was historically not the case; for the nearly 19 years spanning from February 1990 (when the data series began) to the end of 2008, jobless workers were almost always more likely to find a job than to give up or retire. There were only two months when this was not the case (March 2003 and December 2005).

In June, the number of people flowing from unemployment into employment (2,330,000) was almost as high as the the number flowing from unemployment out of the labor force (2,481,000), but not quite. Fingers crossed, maybe next month we’ll finally see those lines cross each other again.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/05/how-one-months-jobless-fare-a-month-later/?partner=rss&emc=rss