CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

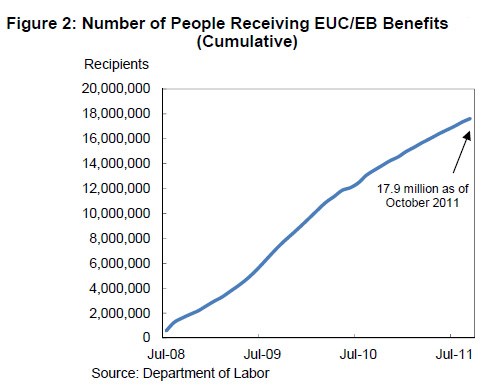

Sunday was the five-year anniversary of the Emergency Unemployment Compensation program, a federal program signed into law by President George W. Bush that initially added 13 weeks of unemployment benefits to the standard 26 weeks states already offered eligible jobless workers. The 13 additional weeks of benefits were intended to be temporary, but as the recession worsened, Congress decided to keep the program going and even lengthened the amount of time that workers could receive benefits. For a while workers could receive as many as 99 weeks in some states, the longest duration of jobless benefits on record.

Those benefits have been pared back over the last year and a half, though, and are being cut more severely now as a result of the across-the-board spending cuts known as the sequester.

A new report from the National Employment Law Project calculates exactly how much: Of the more than $80 billion in automatic budget cuts that must occur between March 1 and Sept. 30, about $2.4 billion is being slashed from the federal emergency unemployment benefits program, says NELP, a labor-oriented research and advocacy group.

The organization estimates that upward of 3.8 million unemployed workers will ultimately be affected by the cuts. The average weekly benefit check of $289 is being cut by $43, or about 15 percent.

“It is the workers who have benefited least from the economic recovery who are bearing the largest share of the burden of the sequester,” the organization said in a statement.

Almost every state has carried out the federally mandated cuts to its unemployment benefits at this point, but many waited until recently to do so. The longer the states took to put the cuts into effect, the sharper the reduction in each remaining weekly benefit check.

For example, the 20 states that cut their benefits starting on March 31 or April 6 trimmed 10.7 percent from each weekly benefit check, whereas Maryland and New Jersey started decreasing benefits on June 30, which required slashing all future weekly checks by 22.2 percent to achieve the total required savings.

The advocacy group has put together a table showing what’s happening in each state, a portion of which is below.

Note that there is one outlier in North Carolina, which on Monday ended its participation in the federal Emergency Unemployment Compensation program altogether. That’s for reasons unrelated to the sequester; basically North Carolina reduced its state-level jobless benefits (which workers go on before qualifying for the later tier of Emergency Unemployment Compensation benefits) by so much that it is no longer legally eligible for the federal extended benefits.

The National Employment Law Project estimated that North Carolina, which has the fifth-highest unemployment rate in the country, is cutting off federal benefits for an estimated 70,000 workers.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/02/sequester-hits-the-long-term-unemployed/?partner=rss&emc=rss