While in Sweden this month as a visiting scholar, I’ve asked several Swedish health economists to share their thoughts about that question. They have spent their lives under a system in which most health care providers work directly for the government. Like economists in most other countries, they tend to be skeptical of large bureaucracies. So if extensive government involvement in health care is indeed a recipe for doom, they should have clear evidence of that by now.

Yet none of them voiced the kinds of complaints about recalcitrant bureaucrats and runaway health costs that invariably surface in similar conversations with American colleagues. Little wonder. The Swedish system performs superbly, and my Swedish colleagues cited evidence of that fact with obvious pride.

The United States spends more than $8,000 a person per year on health care, well more than twice what Sweden spends. Yet health outcomes are far better in Sweden along virtually every dimension. Its infant mortality rate, for example, was recently less than half that of the United States. And males aged 15 to 60 are almost twice as likely to die in any given year in the United States than in Sweden.

In fairness, those differences result partly from lifestyle. In Sweden, workers are more likely to commute by bicycle than by car, for example, and obesity is far less common. Absolute poverty and income inequality — both associated with adverse health outcomes — are also lower.

But when illness strikes, the Swedish health care system responds efficiently. Managers have exploited economies of scale by consolidating services into fewer but larger hospitals. The American system has also gone through consolidation, but, by contrast, boutique hospitals are also more common here — partly in response to demands from patients with very high-cost health plans. In large hospitals, CT scanners and other expensive diagnostic and treatment machines are in nearly constant use, versus only a few hours of weekly use in some small ones.

Larger hospitals with heavier patient flows also enable their staff to hone their skills through specialization and experience. If you are getting a knee replacement or coronary bypass surgery, you want teams that do scores of such procedures each month.

Doctors in the two countries also face different financial incentives. In the United States, under the fee-for-service model, they can bolster their incomes, often substantially, by prescribing additional tests and procedures. Most Swedish doctors, as salaried employees, have no comparable incentive.

Another important difference is that, unlike many American health insurance providers, the government groups that manage Swedish health care are nonprofit entities. Because their charge is to provide quality care for all citizens, they don’t face the same incentive to withhold care that for-profit organizations do. That more hip-replacement operations are performed per capita in Sweden than in most other countries is almost certainly a reflection of the generous care options rather than of any inherent deficiency in Swedes’ hip joints.

The Swedes also provide drugs and other treatments only when evidence establishes their effectiveness. People can spend privately on unproven treatments, but the government refuses to impose their cost on taxpayers.

IS there a catch? When I asked my Swedish hosts to describe any downsides to their system, several mentioned the waiting times for certain nonemergency services. One told me that whereas in the United States a wealthy or well-insured patient might schedule a hip replacement with only a week’s notice, in Sweden the wait could be as long as three months. He described such waits as a design feature, noting that they allowed facilities to be used at consistently high capacity, and thus more efficiently.

Obamacare also contains many evidence-based provisions for medication and other treatments. But at least in its initial stages, it will not be able to match the cost savings achieved in Sweden.

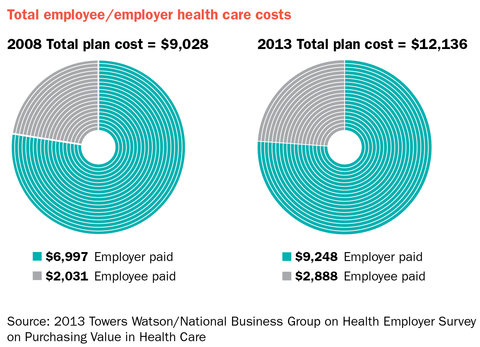

That’s because the legislation’s design was heavily constrained from the outset. Surveys showed that most Americans were satisfied with the existing health plans provided by their employers, so any new system that required people to abandon them would have been a political non-starter. As I discussed in an earlier column, however, such plans are an extremely inefficient way to pay for health care. They arose as an unfortunate historical accident during World War II, when employers used them to sidestep the wage controls that had resulted in extreme labor shortages.

Employer health plans have been disappearing steadily, and may one day be gone entirely. The encouraging news is that the Affordable Care Act was intended to foster the evolution of a new system that can capture many of the gains currently enjoyed by countries like Sweden.

For that to happen, however, Congressional critics must abandon their futile efforts to repeal Obamacare and focus instead on improving it. Their core premise — that greater government involvement in health care provision spells disaster — lacks support in the wealth of evidence from around the world that bears on it.

The truth appears closer to the reverse: Because of pervasive market failures in private health care markets, this may be the sector that benefits most from collective action.

Robert H. Frank is an economics professor at the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University.

Article source: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/16/business/what-sweden-can-tell-us-about-obamacare.html?partner=rss&emc=rss