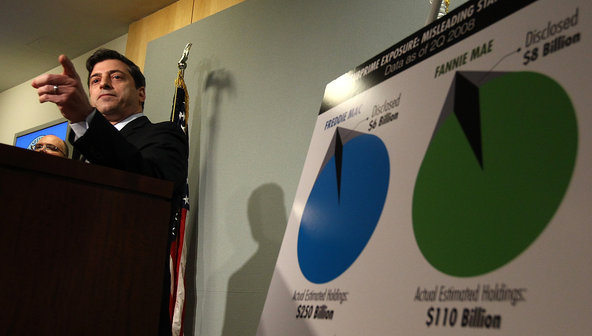

Win McNamee/Getty ImagesRobert Khuzami of the S.E.C. announcing the lawsuits against six former top executives of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Win McNamee/Getty ImagesRobert Khuzami of the S.E.C. announcing the lawsuits against six former top executives of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

9:30 p.m. | Updated

Regulators have accused the former chief executives of the mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac of misleading investors about their firms’ exposure to risky mortgages, one of the most significant federal actions taken against those at the center of the housing bust.

The lawsuits filed Friday against the two chief executives and four other top executives are an aggressive move by the Securities and Exchange Commission, and come after a three-year investigation.

The agency has come under fire for not pursuing top Wall Street and mortgage industry executives who contributed to the financial crisis. In cases contending the deceptive marketing of securities tied to mortgages, the S.E.C. has been criticized for citing only midlevel bankers while settling with the Wall Street firms themselves. Recently, the agency drew criticism from a federal judge after allowing Citigroup to settle a fraud case without conceding wrongdoing.

On Friday, S.E.C. officials trumpeted their actions in the Fannie and Freddie case as part of a renewed effort to crack down on wrongdoing at the highest levels of Wall Street and corporate America.

“All individuals, regardless of their rank or position, will be held accountable for perpetuating half-truths or misrepresentations about matters materially important to the interest of our country’s investors,” said Robert S. Khuzami, the agency’s enforcement chief. “Investors were robbed of the opportunity to make informed investment decisions.”

He noted that the agency had now filed 38 separate actions stemming from the 2008 financial crisis.

The former Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac executives have vowed to challenge the government, saying that the companies repeatedly disclosed the breakdowns of their loan portfolios.

As companies that fed both the housing bubble and Wall Street’s appetite for risk, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac came under investigation quickly by federal agencies amid the financial crisis in 2008. But Freddie Mac disclosed this summer that the Justice Department’s inquiry into the company had ended without any charges. And the S.E.C stopped short of bringing actions against the two companies.

Instead, agreements with Fannie and Freddie will allow the now government-controlled companies to evade prosecution and fines so long as they cooperate with authorities. The deal does not require approval from a federal court, unlike the proposed settlement with Citigroup.

The case against the former executives, including Daniel H. Mudd, the former chief executive of Fannie Mae, and Richard F. Syron, the former chief of Freddie Mac, centers on a series of disclosures the firms made to investors at the height of the mortgage boom. The government contends that the firms played down the extent of their exposure to subprime mortgages, loans doled out to the riskiest of borrowers.

One S.E.C. complaint contends that Freddie Mac executives falsely proclaimed that the company had virtually no exposure to ultra-risky loans, despite internal warnings admonishing against such claims.

A separate complaint contends that Fannie Mae executives described subprime loans as those made to individuals “with weaker credit histories” while only reporting one-tenth of the loans that met that criteria in 2007. Both complaints were filed in the United States District Court in Manhattan.

Mr. Mudd, who was chief executive of Fannie Mae from 2005 until the government took control of the company in 2008, said that there had been no deception.

“The government reviewed and approved the company’s disclosures during my tenure, and through the present,” he said in a statement. “Now it appears that the government has negotiated a deal to hold the government, and government-appointed executives who have signed the same disclosures since my departure, blameless — so that it can sue individuals it fired years ago.”

The S.E.C.’s commitment to the long-running investigation — more than 100 depositions were produced over its course — highlights the major roles that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac played in the financial crisis and subsequent government bailout. The Bush administration took over the teetering mortgage giants in September 2008, and taxpayers have since pumped more than $150 billion into the two companies. The Obama administration has vowed to wind them down, although the timeline remains unclear.

The case against the former mortgage executives resembles an earlier action against one of the nation’s biggest lenders to risky, or subprime, borrowers. Angelo Mozilo, the former chief executive and founder of Countrywide Financial, agreed to pay $22.5 million to settle federal charges along the same lines. The settlement was the largest ever levied against a senior executive of a public company, though Mr. Mozilo, who also agreed to forfeit $45 million in gains, neither admitted to nor denied wrongdoing.

Success for the S.E.C. in the Fannie and Freddie case will largely hinge on the meaning of the word subprime, which the government itself has never fully defined. While the term often refers to borrowers with low credit scores, Fannie and Freddie decided to classify loans as prime or subprime based on the lender type, not the borrower’s credit score. A Wall Street bank, for instance, was usually considered a prime lender, despite extending subprime loans.

But the government’s complaint contends that this kind of disclosure masked risk. Loans not considered subprime often defaulted at higher rates than those classified as subprime.

The government contends that the executives were less than forthcoming about that extra layer of risk. Mr. Syron told an investor conference in May 2007 that the company had “basically no subprime business.”

But a lower-level executive at the firm, who reviewed Mr. Syron’s speech in advance, warned that such a statement could be misleading.

“We need to be careful how we word this. Certainly our portfolio includes loans that under some definitions would be considered subprime,” the employee said, according to the complaint. “We should reconsider making as sweeping a statement.”

Mr. Mudd, meanwhile, testifying before Congress in April 2007, broadly defined subprime as “the description of a borrower who doesn’t have perfect credit.” But at the same hearing, he told lawmakers that “less than 2.5 percent of our book of business can be defined as subprime,” which the complaint says greatly understated the firm’s exposure based on his definition that day. Mr. Mudd’s estimate omitted some $50 billion in subprimelike loans, according to the complaint.

Lawyers for the executives, however, plan to argue that the firms did in fact disclose minute details of their loan portfolios, suggesting a potential weakness in the case. During the period under scrutiny, the companies produced “monster charts” breaking down their loan portfolios by borrowers’ credit scores and how much equity they had in their homes, among other information.

Lawyers for Mr. Syron called the S.E.C.’s case “fatally flawed” and “without merit.”

“Simply stated, there was no shortage of meaningful disclosures, all of which permitted the reader to assess the degree of risk in Freddie Mac’s guaranteed portfolio,” Thomas C. Green and Mark D. Hopson, partners at Sidley Austin, said in the statement.

The lawyers note that even the federal government never settled on a definitive meaning for subprime. Indeed, in a 2007 document, multiple federal agencies declined to define it.

Lawyers for two of the other executives named in the suit have also promised to fight the allegations.

The complaints also name Fannie’s former risk officer, Enrico Dallavecchia; an executive vice president for Fannie, Thomas A. Lund; Patricia L. Cook, Freddie’s former chief business officer; and its executive vice president, Donald J. Bisenius.

Still, Mr. Mudd and Mr. Syron are the two most prominent subjects of the complaint.

Since August 2009, Mr. Mudd has been chief executive of the Fortress Investment Group, the large publicly traded private equity and hedge fund company.

Mr. Syron is a former president of the American Stock Exchange and currently an adjunct professor and trustee at Boston College.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=bf9883ed2fef5a99a98d85d406156d75