Carl Richards

Carl Richards

Investors typically set up a diversified investment portfolio to reduce their risk. Just hold a good mix of different kinds of stocks, along with some bonds and cash, and your problems are over.

Right?

Not exactly. Diversification comes with its own risk. But before we get to the risk, let’s talk about how we define this term in the first place.

When people say diversification, they’re often talking about two separate things. First, there’s equity diversification where you split up the portion of your money invested in stocks among big ones, small ones, undervalued ones, international ones and so on.

The idea behind this strategy is that you can reduce your risk, since different types of stocks often behave differently depending on market conditions.

Sometimes, it works. Dimensional Fund Advisors reported that in 1998, the large company stocks that make up the S.P. 500 gained 28.6 percent while small-cap value stocks lost 10 percent. Then in 2001, the S.P. 500 was down 11.9 percent, while those same small-cap value stocks gained 40.6 percent.

Since it does help sometimes, equity diversification is a useful strategy. Do it. But you have to understand that equity diversification sometimes fails to deliver exactly what you expect it to and often fails when you need it most.

We saw this in 2008-2009, when almost every type of investment fell. Granted, diversification would have saved you from making a mistake like putting everything in Lehman Brothers stock, but you still saw equity holdings plummet.

If you think back to that time, you will most likely remember hearing people say that diversification was broken, that it no longer worked. I remember thinking that myself.

But remember, when that happens and people start running around again saying diversification doesn’t work, they’re talking about equity diversification. There’s another, more important type of diversification: the way you split your money between stocks, bonds, cash and other investments.

This portfolio-level diversification is the primary lever to help you manage the risk and return in your portfolio. Each type of investment plays a different role:

- Stocks provide the growth.

- Short and intermediate bonds provide more safety and a little income.

- Cash is there for liquidity and to protect your money.

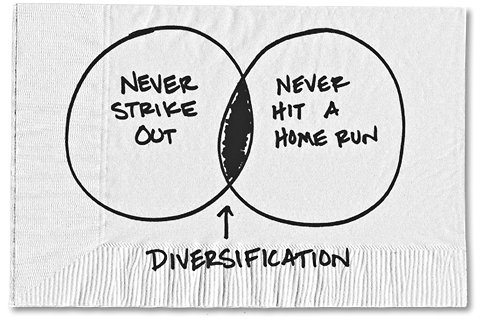

The idea is to balance these investments in a way that gives up some higher returns in exchange for lower overall risk. Essentially, you’ve given up the opportunity to hit home runs for the benefit of never striking out.

With that out of the way, let’s talk about the risk of diversification.

Whenever you diversify, if you’ve done it correctly, there will always be something in your portfolio that you’re in love with and something that you want to dump (or will at least be the source of concern, as bonds are now in some circles). Some investment or asset class will be doing fantastic compared to the rest of your portfolio, and something will be doing much worse than everything else.

The trouble is, you never know when all of this will change. The thing you want to buy more of now will someday become the thing you want to sell.

Think back to the example from 1998. Having lived through it, I can tell you it was awfully tempting to move all your money out of small-cap value stocks and into large-cap stocks. But that would have been a terrible decision given how well small-cap value stocks did just two years later.

The same is true when you diversify among stocks, bonds and cash. When the stock market is tumbling like it did in 2008, you want to move everything to cash, and it’s really hard to keep money in bonds or cash when the stock market is having one of those great years.

But here is the point. The risk of diversification is that you will bail on it as a strategy at exactly the wrong time.

That feeling you get — the one that says, I wish I could dump this lame investment so I could buy a whole bunch more of this incredibly hot one — can get you into trouble fast. The temptation is greatest when it would be the most catastrophic for you to succumb.

But that feeling is actually telling you that you’ve done the right thing: You’re diversified. So remember that when the current fad ends and today’s rejects come back into style, you’ll be okay. And you’ll be awfully glad you didn’t give in to the temptation to give up on being diversified.

The next time diversification appears to not be working, remind yourself that it is a long-term strategy that can’t be judged on your short-term experience. In other words, just because something isn’t working right this minute — or even right this year — doesn’t mean it’s broken. So instead of thinking, “I am a rocket scientist and I can come up with something better,” just let diversification do its job.

Then go for a hike in the mountains instead of sitting hunched over the sell button on your broker’s Web site.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/31/let-diversification-do-its-job/?partner=rss&emc=rss