WASHINGTON — The number of people seeking unemployment benefits for the first time rose last week, the Labor Department said Thursday, but the broader trend over the past month suggested job growth could pick up in the new year.

Meanwhile, an index of signed contracts for home purchases in November rose 7.3 percent to 100.1 points, the highest level in a year and a half, according to a report Thursday from the National Association of Realtors.

A reading of 100 points is considered healthy, but a growing number of buyers are canceling their contracts at the last minute, making the gauge less reliable.

Weekly applications for jobless benefits increased by 15,000 to a seasonally adjusted 381,000 after three weeks of declines, the Labor Department said.

Still, the four-week average, a less volatile measure, dropped for the fourth consecutive week to 375,000. That’s the lowest level since June 2008.

Applications generally need to fall consistently below 375,000 to signal that hiring is strong enough to reduce the unemployment rate.

While layoffs have fallen sharply since the recession officially ended two and a half years ago, many companies have been slow to add jobs.

Still, employers have added an average of 143,000 net jobs a month from September through November, almost double the average for the previous three months.

Next year is expected to be even better. A survey of 36 economists by The Associated Press this month found that they predicted the economy would generate an average of about 175,000 jobs a month in 2012.

More small businesses plan to hire than at any time in three years, a trade group said earlier this month. And a separate private-sector survey found more companies are planning to add workers in the first quarter of next year than at any time since 2008.

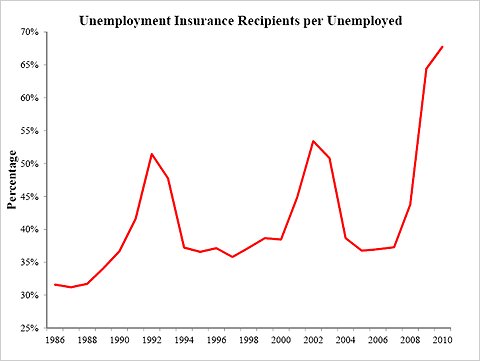

In November, the unemployment rate fell to 8.6 percent from 9 percent. Still, about half that decline occurred because many of the unemployed gave up looking for work. When people stop looking for a job, they’re no longer counted as unemployed.

And Congress last week agreed to keep emergency unemployment benefits for two additional months. Economists worried that ending the extended unemployment benefits program would have left Americans with less money to spend.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=95ee6c54b021b52bd871d53658cfafcc