My column on Wednesday startled some readers. Was I proposing to do away with corporate taxes simply because globalization is making it easier for multinational companies to avoid them? Should we really just roll over and accept defeat?

Well, other advanced nations seem on their way to doing exactly that.

They have found a way of reducing corporate tax rates that improves economic efficiency, lowers the cost of capital for their companies and may even increase the progressivity of their tax system: offsetting those lower corporate rates with higher tax rates on the income that companies provide to their shareholders.

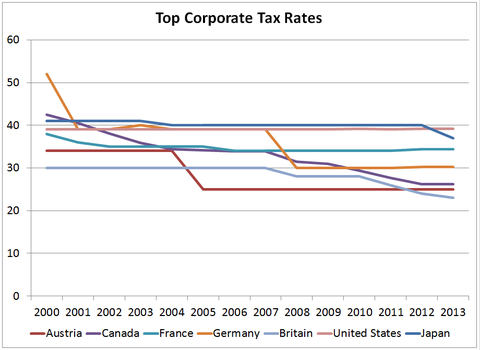

Since 2000, the top corporate tax rate in Britain has fallen to 23 percent, from 30 percent; in France it has receded to 34.4 percent, from 37.8 percent, and in Denmark it has declined to 25 percent, from 32 percent, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Source: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

Many of these countries have compensated for lowering the corporate rates by taxing dividends more. Over the same period, the dividend tax rate rose to 30.6 percent in Britain, from 25 percent; in France, it went to 44 percent from 40.8 percent, and in Denmark it rose to 42 percent from 40 percent. Most industrial countries have also eliminated exemptions to prevent double taxation of dividends.

The United States has rowed in the opposite direction. Companies complain, rightly, that the corporate tax rate in the United States is too high compared to those of its peers: 39.1 percent, combining federal and state taxes – virtually the same as it was 13 years ago. But they rarely mention that the tax on profits flowing to shareholders has fallen drastically.

Even after the New Year’s budget deal raised taxes on the highest earners, the 20 percent top rate for dividends and long-term capital gains remains much lower than in the 1990s — when the top capital gains tax was 28 percent, and dividends were taxed as ordinary income.

A paper published a couple of years ago by Rosanne Altshuler of Rutgers, Benjamin H. Harris of the Brookings Institution and Eric Toder of the Tax Policy Center suggested that the American mix is particularly inefficient.

Because American corporate tax mostly falls on domestic profits (foreign profits retained abroad pay no tax), it raises the cost of domestic investment and encourages companies to invest abroad. It also encourages them to seek out low-tax havens around the world to park their profits. And it encourages companies to shed their corporate status to avoid the tax altogether.

The Altshuler-Harris-Toder paper suggests that reducing the corporate tax rate and increasing taxes on dividends and capital gains would be a much more efficient way to raise money.

Their calculation — which is only rough because it assumes no change in the behavior of companies or their shareholders — suggests that raising the top tax on long-term capital gains to 28 percent and taxing dividends as ordinary income (which faced a top rate of 35 percent at the time of the study) would raise enough money to pay for a cut in the federal corporate tax rate from 35 to 26 percent.

But the most interesting bit of the study is their finding that these changes would make the tax structure more progressive – increasing the tax burden on Americans with the highest incomes. That’s because the rich would bear the brunt of the increase in the dividend and capital gains tax.

Even assuming that shareholders bear the entire burden of corporate taxation — an assumption that is being questioned in the economic literature — the change suggested by the economists would lower the average federal tax rate of everybody except the top 1 percent of Americans, who would suffer a tax increase of 1 percent.

Under a different assumption — that corporate taxes are mostly paid by workers because of the impact of the tax on investment, jobs and wages — the progressivity would be steeper. In particular, those in the top percentile of income would see their taxes rise by 1.8 percent.

So getting rid of corporate taxes — or at least reducing them substantially — may not be such a bad idea. The tax burden would just have to be shifted from the companies to their owners.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/31/kissing-away-the-corporate-tax/?partner=rss&emc=rss