After resisting for a decade, the parent company of American Airlines announced Tuesday that it would now follow a strategy that the rest of the industry chose long ago: filing for bankruptcy protection so it can shed debt, cut labor costs and find a way back to profitability.

American’s parent, the AMR Corporation, was the last major domestic airline that had never sought Chapter 11 protection. Its main rivals, including Delta Air Lines and United Airlines, used the bankruptcy courts to reorganize their businesses in recent years and emerged as stronger, more profitable rivals.

Related Links

Graphic: Another Airline Seeks Help With Court Protection

Graphic: Another Airline Seeks Help With Court Protection- For AMR’s Now-Former Chief, a Long Career Felled by Chapter 11

- AMR Filing Is 2nd-Largest by a U.S. Airline

American, meanwhile, has lost more than $11 billion since 2001, while falling off its perch as the nation’s largest airline as mergers between first Delta and Northwest, and then United and Continental, created bigger competitors. The airline’s troubles were compounded by high labor costs, including pensions that are the richest in the industry, and surging fuel prices.

The decision to file for bankruptcy, which was endorsed by a unanimous vote of the company’s board on Monday evening, was a defeat for Gerard J. Arpey, who has run the airline since 2003 and had staunchly resisted such a move.

Ángel Franco/The New York TimesAmerican’s counter at La Guardia Airport on Tuesday. The airline says it will run a full schedule while it is in bankruptcy.

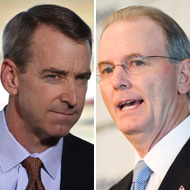

Ángel Franco/The New York TimesAmerican’s counter at La Guardia Airport on Tuesday. The airline says it will run a full schedule while it is in bankruptcy. Richard W. Rodriguez/Associated Press and Brandon Thibodeaux/Getty ImagesThomas Horton, left, succeeds Gerard Arpey as chief executive.

Richard W. Rodriguez/Associated Press and Brandon Thibodeaux/Getty ImagesThomas Horton, left, succeeds Gerard Arpey as chief executive.

“It’s no secret that we have tried exceptionally hard over the last decade to avoid this outcome,” he wrote in an emotional message to employees.

Rather than guide the airline through bankruptcy, Mr. Arpey, 53, decided to retire as chairman and chief executive and take a job in private equity investing. He was succeeded by AMR’s president, Thomas W. Horton, 50, another longtime hand at the airline, who was ATT’s chief financial officer for four years before returning to AMR in 2006.

Despite Mr. Arpey’s long tenure as AMR’s chief executive, he does not appear to be bailing out with a golden parachute. Under the terms of his contract, he will not receive any severance, according to the research firm Equilar. And with AMR closing at 26 cents a share on Tuesday, his stock holdings are essentially worthless.

As other airlines have done in similar cases, American said it would continue to operate its regular schedule throughout the bankruptcy process. It said flights, ticket sales, overseas alliances and frequent flier programs would not be affected. Employees will continue to be paid and receive health benefits.

Wall Street analysts said AMR, which has about $4.1 billion in cash and short-term investments, was seeking court protection before its financial position completely deteriorated.

“This is not a defensive move, but an offensive bankruptcy where they go after their labor groups to reduce costs,” said Bob McAdoo, an airline analyst at Avondale Partners. “They have a great franchise and a lot of cash. They are not being forced into bankruptcy here. They have a problem with their cost structure that they want to tackle.”

The decision might eventually lead to a smaller airline, with fewer employees, fewer planes and fewer destinations. Seth Kaplan, an aviation specialist with Airline Weekly, said hubs like Dallas and Miami, where American has a strong competitive position, would probably be spared, while Los Angeles and Chicago, where it is not a market leader, might be more vulnerable to cuts.

American has long argued that its labor costs were $800 million a year higher than its rivals’ because its pilots fly fewer hours and have less flexible work rules. Its cost per available seat mile, a common industry metric that includes labor and operating costs, is about 10 percent higher than Delta’s.

But labor is only part of the picture. American owns and operates a regional carrier, American Eagle, that flies 50-seat jets that are among the least efficient to operate. It is also the only major airline to perform most of its major maintenance internally. And more than a third of its 600 planes are McDonnell Douglas MD-80s, an aging design that burns more fuel than newer models.

“If oil was still at $50 a barrel, we wouldn’t be having this conversation,” said Mike Boyd, an airline consultant. “Their bet was to hold on to their older MD-80s until Boeing came up with a new airplane. As we know, that didn’t happen.”

The decision to file for bankruptcy was not entirely unexpected. Speculation about a bankruptcy sent the company’s shares down 79 percent this year even before the filing. However, its timing did take many analysts by surprise because they thought the company had enough cash to finance its operations for at least the next 12 months.

Mr. Horton said in an interview that AMR’s board did not want to wait. “This was the time to move from a position of relative strength,” he said. As of Sept. 30, AMR had $24.7 billion in assets and $29.6 billion in debt, according to a filing with the Federal Bankruptcy Court in Manhattan. Creditors include the holders of AMR bonds as well as companies like General Electric that leased aircraft to the airline.

The airline managed to avoid filing for bankruptcy in 2003 after it obtained major concessions from its labor groups, including lower pay for its pilots. But talks for a new contract had been dragging on since 2008 with no resolution. The latest round stalled in recent weeks when the pilots’ union refused to send a proposal to its members for a vote.

“It appears the board of directors ran out of patience after the last discouraging signals from the pilot unions,” said Philip Baggaley, a managing director at Standard Poor’s Ratings Services.

Airlines have used federal bankruptcy rules in the past to force new contracts on their employees, and American may now take a tougher position with its own unions.

“We had been hopeful that bankruptcy could be averted, but we were aware of the possibility,” said Gregg Overman, a spokesman for the Allied Pilots Association, which represents American pilots.

James C. Little, the president of the Transport Workers Union of America, which represents 25,000 employees, including ground workers, struck a more defiant tone. The union reached a series of tentative agreements in recent weeks with the airline and American Eagle.

“This is likely to be a long and ugly process, and our union will fight like hell to make sure that front-line workers don’t pay an unfair price for management’s failings,” he said.

The mergers of Delta and Northwest, and United and Continental, helped those airlines cut capacity, increase fares and return to profitability last year. American, meanwhile, has had just two profitable years in the last decade, while losses from 2001 to 2010 were $11.4 billion. It recorded a $982 million loss through the first nine months of this year and is expected to post another loss in 2012.

In the long run, the airline is counting on a significant overhaul of its fleet to cut long-term costs. In July, it announced a $38 billion order for 460 new single-aisle planes from Airbus and Boeing. American’s fleet has an average vintage of 15 years, making it one of the oldest and least fuel-efficient among the six major United States carriers.

The company said it still intended to buy these planes, for which it has already secured $13 billion in financing from the plane makers themselves.

The impact of the bankruptcy is likely to be more immediate for some jet leasing companies. In a letter addressed to lessors, American’s treasurer, Beverly K. Goulet, said the airline could not afford to maintain all of its leased aircraft at their current rates and said it had no choice other than to begin canceling contracts on an unspecified number of planes. American leases roughly 29 percent of its fleet, according to data compiled by Ascend, an aviation consultancy based in London.

Although other airlines have improved their finances by taking a trip through bankruptcy court, some analysts were still skeptical about American’s long-term prospects.

“The industry is chronically oversupplied and AMR has no dominance or significant competitive edge in any particular market — we are not convinced that a reinvented, scaled-down iteration will change that,” said Vicki Bryan, an analyst at Gimme Credit.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=36a3aff91655e51e5d0c196efa1d47b0