Carl Richards

Carl Richards

Carl Richards is a financial planner in Park City, Utah, and is the director of investor education at the BAM Alliance. His book, “The Behavior Gap,” was published this year. His sketches are archived on the Bucks blog.

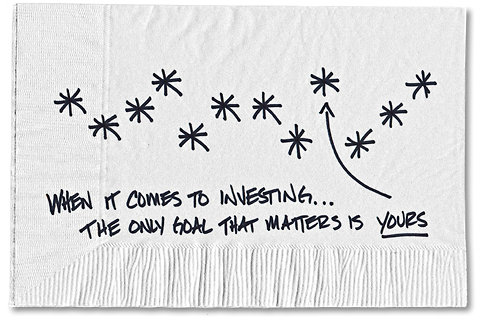

Most of what we hear about investing isn’t right or wrong. It’s a matter of applying what we hear to our own situation.

When we make investment decisions, they should be tied to our goals. We get into big trouble when we either:

a) Fail to get clear about our goals

b) Invest based on someone else’s goals

I’ve written before about the first situation. But as my friend Tim Maurer says, personal finance is much more personal than it is finance. We need to take the time to be really clear about our goals.

The second situation is a more nuanced situation. It can happen subtly, because a lot of what we hear and do when it comes to investing is basically based on folklore. We end up doing things because other people are doing them, and it leads to big problems.

Here are a few examples:

- You hear that Harvard’s endowment is buying dairy farms in New Zealand.

- You hear your wealthy uncle talking about how important it is to own municipal bonds. He has to be really smart because he’s so wealthy, right? And what he’s saying sounds so sophisticated that you think there has to be something there.

- You hear the cool kids who just got hired out of Stanford’s M.B.A. program talking about investing 100 percent of their 401(k) in stocks. (They must be smart too. They went to Stanford!)

In all three examples, you might be tempted to change your investments based on something you’ve heard from someone else. But while dairy farms, municipal bonds and stocks might be good investments, you aren’t just looking for good investments. You’re looking for good investments that will help you reach your goals.

Your goals are not Harvard’s. Harvard’s goal is based on a different time frame, to build an endowment that will be around forever. You, however, many have goals to meet in 10, 20 or 30 years.

And your goals are not your wealthy uncle’s goals. He’s probably interested in buying municipal bonds because of his ridiculously high tax bracket and the tax-free status of the bonds.

Finally, your goals are probably different from the goals of people who just finished business school. Clearly, these young hotshots feel like they can afford to be extremely aggressive when setting up their retirement portfolios. Most of us are in a different situation.

Your goals are just that: Yours.

It’s not that Harvard, your uncle and the business school graduates are wrong and you’re right. The point is that when it comes to investing your money, the only goals that matter are yours.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/24/dont-mistake-investing-folklore-for-personalized-advice/?partner=rss&emc=rss