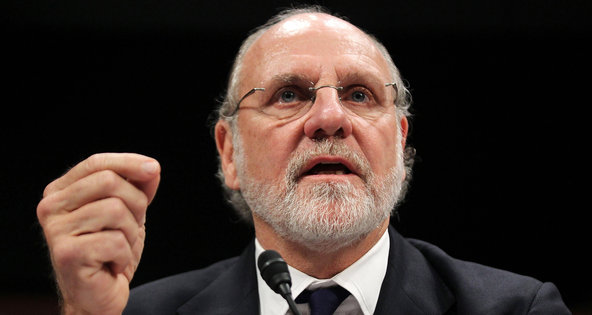

Jonathan Ernst/ReutersJon S. Corzine, former MF Global chief. Some lawyers are skeptical of the outcome of talks with the bankruptcy trustee.

Jonathan Ernst/ReutersJon S. Corzine, former MF Global chief. Some lawyers are skeptical of the outcome of talks with the bankruptcy trustee.

A day after MF Global’s bankruptcy trustee hinted he might sue top executives for “negligent conduct,” his separate plan to liquidate the firm secured court approval, ushering in a final phase of a case that rattled Wall Street and prompted a federal investigation.

At a hearing in bankruptcy court in Manhattan on Friday, nearly 18 months after the brokerage firm imploded, Judge Martin Glenn cleared the way for Louis J. Freeh, the trustee, to sell the firm’s remaining assets and return money to creditors. For Mr. Freeh, a former director of the F.B.I. who is liquidating MF Global’s estate, the ruling was a major step toward ending the largest Wall Street bankruptcy since the financial crisis.

When the firm collapsed — and improperly tapped customer money to plug a gap in its own finances — the blowup consumed Wall Street and Washington. MF Global, then run by Jon S. Corzine, the former governor of New Jersey, became a byword for excessive risk-taking and the target of a federal investigation into $1.6 billion in missing customer money.

Criminal and civil investigations continue. And in a report released on Thursday, Mr. Freeh suggested that he might sue Mr. Corzine and other top executives, accusing them of engineering a “risky business strategy” and ignoring “glaring deficiencies” in internal controls.

Related Links

Mr. Freeh pointed to Mr. Corzine’s outsize bet on European debt. While the bonds were not by themselves to blame for the fall of MF Global, the bet alarmed investors and rating agencies, sending the firm into a tailspin.

Mr. Freeh agreed to postpone the lawsuit while he pursued mediation with Mr. Corzine. A spokesman for Mr. Corzine argued that “there simply is no basis for the suggestion that Mr. Corzine breached his fiduciary duties or was negligent.” The spokesman, Steven Goldberg, added that “the trustee’s report, with its allegations of negligent conduct, is a clear case of Monday-morning quarterbacking.”

Judge Glenn’s decision to approve the liquidation plan will empower Mr. Freeh to wind down his role in the case. When the plan becomes effective, he will hand the reins in part to a committee of MF Global creditors.

Mr. Freeh attended the hearing on Friday to speak in favor of the liquidation deal.

Under the plan, MF Global will pay up to 34 percent of claims filed by hedge funds and other unsecured creditors that owned MF Global bonds. The hedge funds, including Silver Point Capital, supported the plan.

JPMorgan Chase, one of MF Global’s largest lenders, will fare better. The bank is expected to collect up to 76 percent of its claims under the plan approved on Friday.

The firm’s customers, whose money vanished after the bankruptcy, are also poised for a big payout. James W. Giddens, a trustee whose job was to return money to customers, has recovered most of the funds from MF Global’s banks and clearinghouses. Mr. Giddens, who already returned about 89 percent of the missing money, recently sought court approval to dole out up to about 97 percent.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/04/05/judge-approves-mf-global-liquidation-plan/?partner=rss&emc=rss