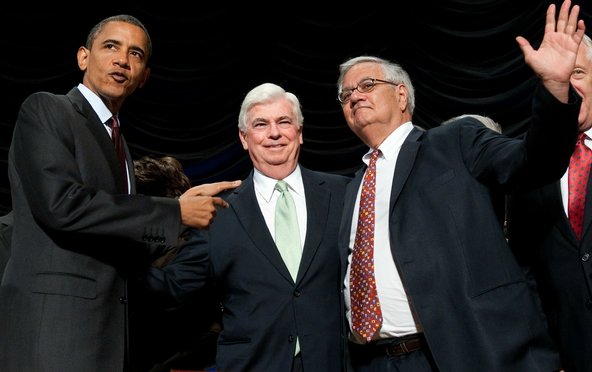

Saul Loeb/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesPresident Obama, with Senator Christopher Dodd, center, and Representative Barney Frank, signed an overhaul of financial regulation in 2010.

Saul Loeb/Agence France-Presse — Getty ImagesPresident Obama, with Senator Christopher Dodd, center, and Representative Barney Frank, signed an overhaul of financial regulation in 2010.

Regulators in Washington have agreed in principle on a plan to rein in risky trading by banks overseas, according to people briefed on the matter, a truce that follows a messy split in the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

The potential deal, subject to final approval by the agency, would be reached with only hours to spare before a deadline on Friday. The commission had established the deadline when it set out to decide how to regulate trading by American banks in London and beyond — a major factor in the 2008 financial crisis.

Until now, the trading commission seemed destined to miss the date. Some officials at the agency, which oversees trillions of dollars in Wall Street activity, had warned that a compromise was proving elusive as tension mounted.

The dispute traced largely to the agency’s Democratic chairman, Gary Gensler, and Mark Wetjen, a Democratic commissioner with an independent streak. While Mr. Gensler was adamant that the agency complete its plan on time, Mr. Wetjen recently called the deadline “arbitrary.” And with the agency’s Republican commissioner pushing for a delay, Mr. Wetjen holds the swing vote.

But in recent days, they showed signs of progress. Mr. Gensler and Mr. Wetjen have been meeting in person throughout the week, the people briefed on the matter said, and had struck a preliminary deal by Wednesday.

While both are likely to claim victory, the deal does not come without sacrifice for each side.

The contours of the plan, the people briefed on the matter said, suggest that firms like Goldman Sachs International and Citigroup’s London branch will face a wave of new scrutiny, a sticking point for Mr. Gensler.

In a move likely to appease Mr. Wetjen, Mr. Gensler is expected to phase in the cross-border oversight. And in a concession to Wall Street and foreign finance ministers, the plan would defer to European regulators if they ultimately agree to scrutinize banks in a way that is similar to the monitoring by the trading commission.

Wall Street, while objecting to the new oversight, would exhale at the prospect of a deal being reached by Friday. If the agency fails to produce the guidelines but declines to extend the deadline, some banks feared widespread confusion would ensue.

The people briefed on the matter, who insisted on anonymity to discuss private negotiations, cautioned that the deal was not final. The agency’s lawyers must now draft the plan to reflect compromises hashed out in recent days. If either side makes last-minute changes, the people said, the deal could collapse.

If the deal is approved, it is unclear when the agency might announce the decision. It tentatively scheduled a public meeting for Friday to vote on the plan, though the agency could also vote in private over the next few days.

The agency’s spokesman, Steven Adamske, declined to say whether the commissioners had struck a deal. Instead, he said that “progress is being made,” adding that “we remain hopeful for a vote on Friday.”

The agency and European regulators are also poised to announce a framework for collaborating in the coming years the people briefed on the matter said. The deal, which is expected to be announced this week, could subdue cross-border tensions among the various regulators.

The delicacy reflects the importance of a plan that took shape after the financial crisis highlighted the risk of overseas trading.

Trades by a London unit of the insurance giant American International Group, for example, nearly toppled the company. And JPMorgan Chase’s $6 billion trading loss in London last year reignited concerns that risk-taking could come crashing back to American shores.

The blowups by A.I.G. and others spurred the Dodd-Frank Act, a law that mandated a sweeping overhaul of the $700 trillion marketplace for derivatives, financial contracts that derive their value from an underlying asset like a bond or an interest rate. Under that 2010 law, the trading commission is supposed to extend new derivatives changes — including tougher capital standards — if overseas trading has “a direct and significant connection with activities” of the United States.

That broad template left it up to the agency to draft a plan for how Dodd-Frank applies to everyday trading overseas. Ever since, Wall Street lobbyists have complained to the agency that certain requirements could drive trading business away from United States banks.

In a statement on Wednesday, the co-authors of the law, Christopher J. Dodd and Barney Frank, called on the trading commission to resist Wall Street’s talking points. The former lawmakers, Mr. Frank, a Congressman from Massachusetts who retired in January year, and Mr. Dodd, a Democratic senator from Connecticut who left office in 2011, cited the chaos of 2008 as the impetus for the crackdown.

“Only people who have never heard of A.I.G. can deny that overseas failures by large domestic entities have direct impacts here,” Mr. Dodd and Mr. Frank said in the statement. “The failure to regulate derivatives as their role in our financial system expanded greatly was one of the most serious weaknesses in the regulatory system which we sought to correct.”

The former lawmakers also said they weighed in with the hope of speeding the agency along.

“I respect that getting it right is not easy, but the fact that it’s taken three years sort of stuns me,” Mr. Dodd, who is now chairman and chief executive of the Motion Picture Association of America, said in an interview on Wednesday. “What do you need to know?”

Mr. Gensler echoed Mr. Dodd’s concerns in a meeting last month with Wall Street lobbyists , who urged the agency to extend its deadline past Friday. Mr. Gensler, summoning into his office a pregnant speechwriter at the agency whose due date was Friday, asked her what she thought of the deadline. In reply, she exclaimed, “No delay.”

The speechwriter, Stephanie Allen, gave birth a week later. Some people said that was a positive omen Mr. Gensler and Mr. Wetjen would make their deadline.

Article source: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/07/10/deal-reached-to-rein-in-overseas-trading/?partner=rss&emc=rss