CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

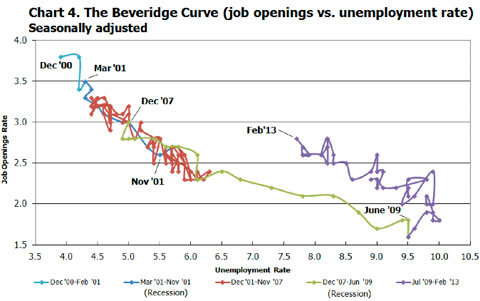

The Labor Department has released its latest report on job openings and labor turnover today, which showed that job vacancies were at their post-recession high in February. But we still have a strangely high unemployment rate relative to the job openings rate, at least when compared with the relationship these two variables had before the recession began.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey and Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, April 9, 2013.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey and Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, April 9, 2013.

The chart above is the Beveridge Curve, named for the British economist William Henry Beveridge. It shows the relationship between the unemployment rate and the job openings rate. As I also explained in an earlier post, during an expansion the jobless rate is low and the job vacancy rate is high; a small share of workers are looking for jobs, and so when employers post a vacancy, the opening can be hard to fill (or alternately, if there are a lot of jobs available, people will not have much trouble finding work, leading to low unemployment).

In a recession, the reverse is true: there is a high unemployment rate and a low vacancy rate. Where you end up on the curve generally depends on where you are in the business cycle, but you will probably be somewhere on or near that line.

Since late 2009, though, the Beveridge Curve has shifted outward. That means that even though today’s job market is not great, there are still more vacancies out there than the unemployment rate alone would have predicted a few years ago.

It’s not clear why that’s the case, but the answer probably involves some combination of skill mismatch; whether all the people who are calling themselves unemployed today might have done so in previous years; and hiring paralysis at firms that have vacancies but are afraid of making a hiring mistake in a still-uncertain economy.

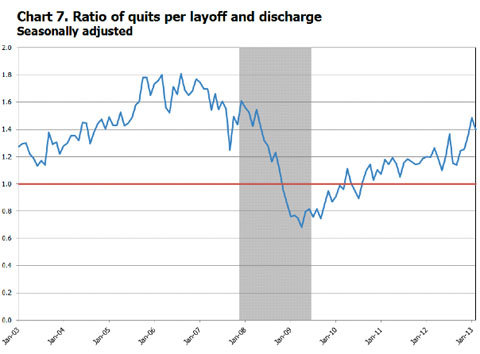

One of the bright spots in today’s Labor Department’s report was that the quits rate (the number of people quitting divided by total employment) held steady at the peak for the recovery period so far. Janet Yellen, vice chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, recently said that she was looking for a pickup in the quits rate as a “signal that workers perceive that their chances to be rehired are good — in other words, that labor demand has strengthened.”

Layoffs and discharges remain quite low; the problem in the job market remains too little hiring, not too much firing.

Here’s a look at the ratio of quits to layoffs/discharges, which as you can see has been generally rising in the last four years:

Bureau of Labor Statistics Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, April 9, 2013. Note: Shaded area represents recession as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bureau of Labor Statistics Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, April 9, 2013. Note: Shaded area represents recession as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The ratio peaked in August 2006, when there were 1.8 people quitting their jobs for each person laid off or discharged. It fell to 0.7 in April 2009, near the end of the recession, and is now about 1.4.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/09/job-openings-rise-but-unemployment-stays-high/?partner=rss&emc=rss