In this excerpt from his new book, “Man vs. Markets,” Paddy Hirsch, senior producer for personal finance at American Public Media’s business radio program production house, Marketplace, explains the basics of lending from the bank’s side of things.

Mr. Hirsch, perhaps best known for his series of whiteboard drawings and videos, leads the Marketplace team that produces two special newspaper sections and two hourlong radio shows each year in partnership with The New York Times.

Today most banks work this way: borrowing money from depositors at one rate of interest, and lending the money out again at another, higher rate of interest. And pocketing the difference.

You might think that makes bankers pretty selfish. They pay measly rates of interest to their depositors and charge higher rates to people who want to borrow from them. In the end they’re firmly focused on making a profit for themselves and their shareholders. The loans they make are a way to make that money.

Fortunately, the banks’ lust for profits works to everyone’s advantage.

The loans the banks make to companies and people usually do a great deal of good. The money helps us to buy everything from groceries to cars and houses, and it helps companies expand and hire. If people are able to borrow (and don’t overstretch), the money they borrow can help grow businesses and create jobs, and that’s good for everyone.

There’s another benefit to banks’ desire to lend money out in order to make profits: Lending creates money. Out of thin air!

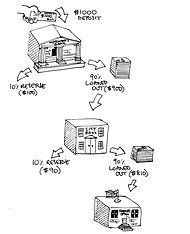

This is how the magic works. One day, Mr. Smith comes to his bank and deposits $1 million. The bank keeps 10 percent, or $100,000, in reserve, in case Mr. Smith wants some of his money quickly.

The next day, Mrs. Jones comes to the same bank and asks for a $900,000 loan, to buy a private jet. The bank lends her the money. Suddenly the amount of money in the system has almost doubled. There’s the million dollars that Mr. Smith has in his bank account. And there’s the $900,000 loan the bank made to Mrs. Jones. Both are assets — Mr. Smith can point to his million-dollar balance on his statement, and Mrs. Jones has a briefcase full of cash — so both are real. The bank has turned a million dollars into $1.9 million, just like that.

Dan Archer

Dan Archer

Mrs. Jones drives out of the airport and gives the briefcase full of cash to Mr. Sharif, of Sharif Aviation. Mr. Sharif gives Mrs. Jones the keys to a gently used Bell 407 helicopter and puts the cash in his bank. The bank puts 10 percent ($90,000) aside as a reserve and lends $810,000 to a clothing manufacturer who needs to buy some new equipment. The clothing maker gives the equipment salesman the $810,000. He takes it to his bank, which holds 10 percent in reserve, and . . .

You get the picture. That $1 million has now more than tripled, in terms of its purchasing power. And yet there’s no new money in the system — it’s still just a million dollars. It’s the banks’ ability to lend that money out, over and over, that creates a ripple effect through the economy and improves everyone’s ability to spend and to grow. Lending and borrowing can be a good thing, in other words. So long as you don’t overdo it.

Which means that banks aren’t all bad. Yes, some banks — or the bankers who run them — do make mistakes. Some bankers cheat, some bankers lie, and some bankers take foolish risks that threaten the entire global economy. But most banks and bankers work to our mutual benefit, and the network of the country’s banks has become an essential part of our economy, driving money through the system like a heart pumping blood around the body.

Excerpted from “Man vs. Markets: Economics Explained (Plain and Simple),” published by Harper Business. Copyright © Paddy Hirsch, 2012. Reprinted with permission.

Article source: http://bucks.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/04/how-lenders-make-money-and-create-it-too/?partner=rss&emc=rss