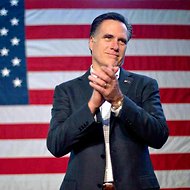

David Goldman/Associated PressMitt Romney’s campaign stopped in Conway, S.C., earlier this month.

David Goldman/Associated PressMitt Romney’s campaign stopped in Conway, S.C., earlier this month.

After a long, controversial wait, Mitt Romney released details of his federal tax returns on Tuesday, inciting a flurry of wide-eyed analysis from those curious to see exactly how Mr. Romney’s personal finances stack up.

DealBook perked up when it saw that many of the assets described in Mr. Romney’s returns were held in blind trusts managed by Goldman Sachs.

As beneficiaries of a blind trust, Mr. Romney and his wife, Ann, would not have picked the individual stocks contained in their trusts’ portfolios. But by examining the trusts’ 2010 returns, a picture emerges of how the Romneys have benefited from – and been hurt by – Goldman’s investment decisions.

In that year, two Romney trusts – the Ann and Mitt Romney 1995 Family Trust and the W. Mitt Romney Blind Trust – made nearly $2.8 million in combined capital gains from their Goldman investments, according to the trusts’ filings. Almost all of those gains, nearly $2.7 million, were long-term gains made by selling securities that the trusts had owned for more than a year.

The trusts sold a combined 7,000 shares of Goldman’s own stock, which was purchased in May 1999 when the firm went public. The shares, offered at the time of the I.P.O. to Goldman’s most important clients, including Mr. Romney, were issued at $53 a share. But they had zoomed up to $161.45 apiece by the time the trusts sold them in December 2010.

Aside from the Goldman I.P.O. shares, the Romneys’ trusts sold several financial stocks in 2010. A January 2010 sale of Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase stock produced a small loss and a small gain, respectively. More common were sales of retail companies like Target, Unilever and Apple.

Mr. Romney’s trusts made money on Research in Motion. His brokers bought shares in the BlackBerry maker in 2006 and 2008, long before the company’s stock began its precipitous slide. Before the worst hit last year, the trusts sold 1,027 shares in RIM, notching gains of more than $30,000.

Other investments didn’t work out so well. The trusts sold shares of Comcast class A stock in January 2010, near the stock’s multi-year low, for thousands of dollars in losses.

But the majority of the trusts’ sales in 2010 posted a profit. (This is not surprising – wealth managers often hold on to underperforming stocks in the hopes that they will recover in value.)

The Romneys’ trusts even owned shares of LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, which controls beverage brands like Dom Pérignon and Veuve Clicquot as well as fashion brands like Marc Jacobs and Fendi.

As a Mormon, Mr. Romney is prohibited from consuming the alcohol in Dom Pérignon. Luckily, his trusts were allowed to own its stock. A January 2010 sale of LVMH shares from the family trust produced a profit of around $20,000.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=df023b12d039e679373f90ff7faec4e6