CATHERINE RAMPELL

Dollars to doughnuts.

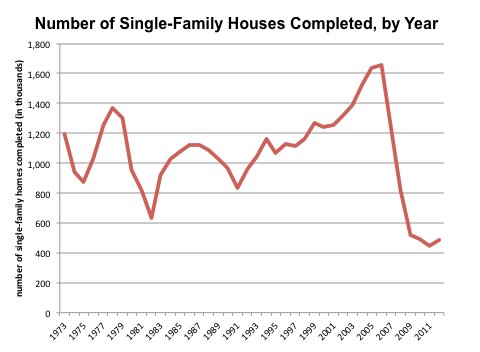

Construction of new homes dropped off a cliff during the housing bust. But where there has been building of single-family homes in recent years, the homes have been getting bigger.

On Monday the Census Bureau released new data on the characteristics of homes built in 2012. Here’s a look at building over the last 40 years, to give you a sense of how sharp the decline in residential construction really was:

Source: Census Bureau.

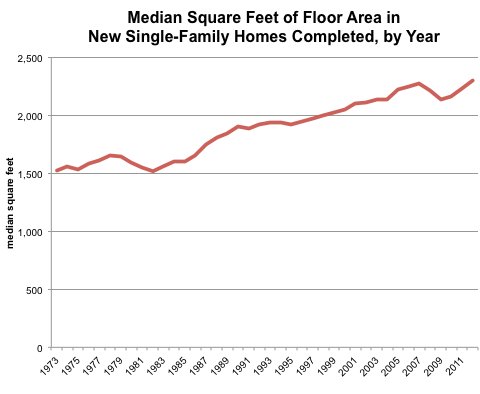

Source: Census Bureau.

For a few years now, though, the size of the typical home built has been growing. For single-family homes, median size rose to 2,306 square feet in 2012, the highest median square-footage for single-family homes since the government began keeping track in 1973.

Source: Census Bureau.

Source: Census Bureau.

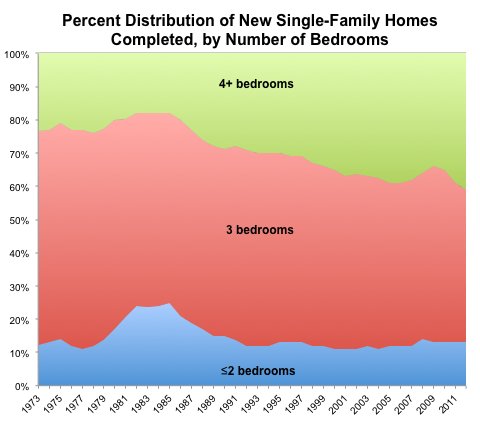

And the number of bedrooms has gone up, too. In 2012, 41 percent of the new homes built had at least four bedrooms, the highest share on record. The median newly built house still had three bedrooms, though.

Source: Census Bureau.

Source: Census Bureau.

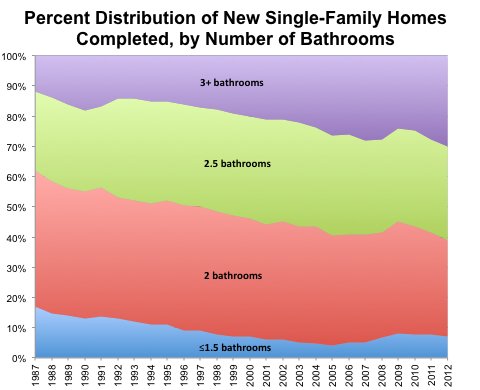

The share of new single-family homes with at least three bathrooms also reached a new high of 30 percent.

Source: Census Bureau.

Source: Census Bureau.

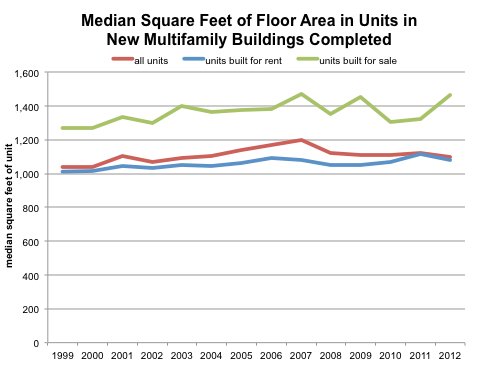

I should note that the same trends don’t hold true for newly completed multifamily housing units. Units built for sale are getting bigger, but the median size of units being built for rent — which represent the vast majority of all multifamily construction — ticked downward from 2011 to 2012.

Source: Census Bureau.

Source: Census Bureau.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/04/the-return-of-mcmansions/?partner=rss&emc=rss