Bruce Bartlett held senior policy roles in the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations and served on the staffs of Representatives Jack Kemp and Ron Paul. He is the author of the forthcoming book “The Benefit and the Burden: Tax Reform – Why We Need It and What It Will Take.”

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

When the most recent recession began in December 2007, there was no reason at first to believe that it was any different from those that have taken place about every six years in the postwar era. But it soon became apparent that this economic downturn was having an unusually negative effect on the financial sector that threatened to implode in a wave of bankruptcies. The Federal Reserve reacted by doing exactly what it was created to do — be a lender of last resort and prevent systemic bank failures of the sort that caused the Great Depression and made it so long and severe.

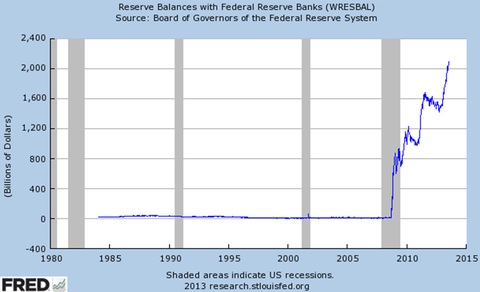

As the Fed lent freely to banks and other financial institutions, its balance sheet grew very rapidly. The reserves of the banking system grew concomitantly; reserves are funds that banks have available for immediate lending that theoretically should lead to credit expansion and new investment by businesses, durable goods purchases by households and so on.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

During the inflation of the 1970s, most economists became convinced that if the Fed adds too much money and credit to the financial system it will inevitably cause prices to rise. Since the increase in the money supply in 2008 and 2009 was unprecedented, many economists reacted fearfully to the Fed’s actions.

Given the order of magnitude of the increase in bank reserves, from virtually nothing to more than $1 trillion almost overnight and now to more than $2 trillion, it was not unreasonable to be concerned about the potential for Zimbabwe-style hyperinflation.

But inflation fell rather than rising. In the five and a half years since the start of the recession, the consumer price index has risen a total of 10.2 percent. In the five and a half years previously, it rose 17.7 percent. That is, the rate of inflation fell by almost half.

Now, I don’t expect all the people who filled The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page in 2008 and 2009 predicting an imminent rise in inflation to offer a mea culpa, but at some point I think the inflationphobes should at least stop saying that hyperinflation is right around the corner.

By 2010, the annual inflation rate was down to 1.5 percent, and the yield on the Treasury’s 10-year bond had fallen to 3.2 percent from 4.3 percent in 2007 – historically, long-term interest rates rise when inflationary expectations rise. In short, there was no evidence that Fed policy was causing inflation to rise.

Yet in November 2010, both Sarah Palin and Paul Ryan warned that inflation was imminent. As they are Republicans, one can assume they were just playing politics, pandering to their constituency. But a week later, a group of professional economists signed an open letter to the Fed chairman, Ben Bernanke, warning that continuation of an easy money policy risked “currency debasement and inflation.”

In 2011, there were still no signs of actual inflation, but the economist Allan Meltzer nevertheless asserted, “Inflation is coming.” He wisely chose not to say when. Writing in The New York Times, the former Fed chairman Paul Volcker made the time-honored slippery-slope argument: a little inflation always leads to higher inflation.

The inflationphobe Niall Ferguson at least acknowledged that official data showed no evidence of inflation but asserted that the data were wrong, that the consumer price index is “a bogus index.” He cited the authority of a Web site called ShadowStats, which, like the Unskewed Polls site that said all polls showing Mitt Romney losing were simply wrong, just arbitrarily adjusts the data to make it conform to its belief that inflation is high, not low.

In 2012, the consumer price index rose just 1.7 percent, but the inflationphobe Amity Shlaes feared that inflation could suddenly appear out of nowhere, apparently because there was hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s. Representative Ron Paul, Republican of Texas, was so alarmed by the danger of inflation that he suspended his presidential campaign to lead a Congressional hearing on the subject in June.

In October 2012, Rick Santelli of CNBC said “printing money” caused the German hyperinflation and the same thing was happening in the United States. He, like other inflationphobes, saw the rising price of gold as an ominous sign of a takeoff of consumer prices.

Since Mr. Santelli made his prediction, the seasonally adjusted monthly inflation rate has been negative 0.2 percent in November 2012, zero in December and January 2013, 0.7 percent in February, negative 0.2 percent in March, negative 0.4 percent in April, 0.1 percent in May and 0.5 percent in June. Without seasonal adjustments, the annual inflation rate was 1.4 percent over that time.

Many conservatives, including the publisher Steve Forbes and Larry Kudlow of CNBC, always say that gold is the perfect forward indicator of inflationary expectations. I’ve often heard Mr. Forbes say that the price of gold is like a thermometer that continually gives us inflation’s temperature in real time.

Most economists think that’s ridiculous, but insofar as the gold price reflects inflationary expectations, its falling price is impossible to reconcile with Fed policy. The Fed has not decreased the money supply and continues its policy of “quantitative easing,” which means further increases in the money supply.

To inflationphobes, all increases in the money supply are inflationary; indeed, many define the word “inflation” to mean a money supply increase rather than a rise in the price level.

Hard-core inflationphobes like Peter Schiff simply ignore the reality of today’s economy and assert without evidence that it is exactly like the inflationary 1970s. Inflation is due any day now and gold is “on the verge of its biggest rally ever,” he said. On June 18, Mr. Paul said gold could go to “infinity.”

To be sure, some inflationphobes never believed their own rhetoric; they were just trying to score political cheap shots or con unsophisticated investors into buying gold – from which the inflationphobe reaped a commission. But many others were sincere in their belief that higher inflation was inevitable.

Intellectually honest inflationphobes need to explain why they were wrong and stop crying wolf or else it will be reasonable to assume they are simply cranks and crackpots.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/07/23/inflationphobia-part-iii/?partner=rss&emc=rss