Two decades ago, the border with Mexico was not as big a priority as it is today. The Border Patrol‘s entire budget was only $362.6 million in 1993 — some $584 million in today’s money. It had 4,028 agents. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, border patrolling wasn’t amazingly effective.

Studies in the mid-1990s found that of all the immigrants trying to enter the United States illegally from Mexico, Border Patrol agents apprehended fewer than half — somewhere between 35 and 45 percent.

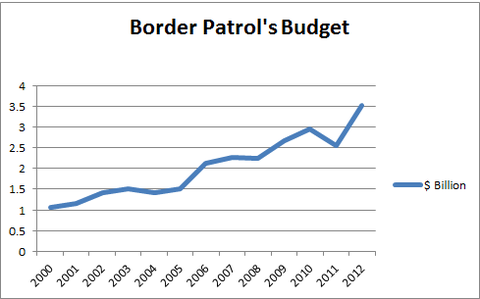

Fast forward to the present and things have changed a lot. The Border Patrol has more than 21,000 agents — 18,500 along the border with Mexico. Its budget last year exceeded $3.5 billion. We have drones and sensors and hundreds of miles of fence.

Source: United States Border Patrol

Source: United States Border Patrol

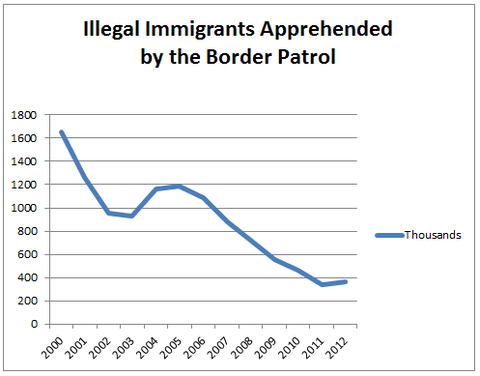

And according to a report by the National Academy of Sciences published last year, Border Patrol agents apprehend about a quarter of those trying to enter the country illegally.

To be sure, these estimates must be taken with a grain of salt. We don’t know how many people are trying to enter the United States illegally in any given year, so it is impossible to tell precisely what share gets caught. Estimates of apprehension rates are derived from statistical analyses that rely on fairly strong assumptions about immigrants’ behavior: How many times do they try to get in after being caught? Are the odds of being caught the same each time?

It is also true that net flows of illegal immigrants from Mexico have fallen to zero over the last few years, because of a combination of slow growth in the United States, expanded legal guest-worker programs and an aging population in Mexico that is slowing the growth of its labor supply. By that measure, the border is as secure as it will ever be.

Source: United States Border Patrol

Source: United States Border Patrol

But the apprehension statistics underscore the vulnerability of the current effort in Congress to pass immigration reform. In my column this week I pointed out how a similar effort six years ago was weakened by disagreements over a guest worker program, which broke apart the coalition of labor, immigrants’ rights advocates and businesses supporting the legislation. Assailed by conservatives — who viewed illegal immigrants as lawbreakers and demanded that the border be secured above all else — the effort failed.

This time around, border security remains a hitch. Some conservative Republicans are still demanding that the border be secured before the first undocumented immigrant gets a green card. But the statistics suggest that an impermeable border is a fantasy, no matter how much money and technology is thrown at it. “Border security is part of a strategy by the anti-immigration constituency to stop reform after the fact,” said Gordon H. Hanson, an expert on the economics of immigration at the University of California, San Diego. “You make the trigger impossible to meet.”

The immigration legislation presented in the Senate sidesteps the issue nicely. Under its proposed legislation, the Border Patrol must put together a plan to keep out 9 of 10 immigrants trying to enter illegally over the most common entry points — a seemingly impossible target. But it is less tough than it seems. The Border Patrol gets to count as success its own estimate of how many run back into Mexico — a fairly unscientific number that can rely on agents’ reading of a footstep in the sand or a broken blade of grass. And those immigrants will surely try again another day.

What’s more, if it doesn’t hit the target within five years, all Congress can do is form a commission to come up with a better plan.

It may be optimistic, however, to assume that this leniency will survive when the legislation falls under the full glare of public scrutiny.

Article source: http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/19/the-challenge-of-securing-the-border/?partner=rss&emc=rss