Uwe E. Reinhardt is an economics professor at Princeton. He has some financial interests in the health care field.

After wrestling for decades and in futility with the triple problems facing health care in the United States – unsustainable spending growth, lack of timely access to health care for millions of uninsured Americans and highly varied quality of care – any new proposal to address these problems is likely to be a recycled old idea.

Today’s Economist

Perspectives from expert contributors.

The widely discussed new proposal from Senator Ron Wyden, Democrat of Oregon, and Representative Paul D. Ryan, Republican of Wisconsin, to restructure the federal Medicare program for the elderly is no exception.

The idea – generally known as “managed competition” — goes as far back as 1971, when Dr. Paul Ellwood and his colleagues at the Health Services Research Center of the American Rehabilitation Foundation injected it into President Nixon’s attempt at health reform.

Since then, the idea has appeared and reappeared in health reform in many variants and with different names, too numerous to permit a full listing here. Its most sophisticated renderings can be found in the extensive writings on the concept by the Stanford economist Alain Enthoven.

To describe the unifying theme running through these past variants, it is helpful to enumerate the major economic functions any health system must perform:

- Producing health-care goods and services.

- Financing health care, which involves extracting money from households (which ultimately pay for all of health care) and funneling it to the producers of health care, usually through the books of private or public health insurers.

- Risk pooling by private or public insurers to protect individuals from the financial inroads of high medical bills through insurance policies.

- In most modern societies, assuring that every member of society has timely access to a defined set of health-care benefits.

- Purchasing medical treatments from the producers of health care, which includes determining the prices to be paid, claims processing for insured patients and controlling overall spending and the quality of that care with various forms of controls lumped together under the generic label “managed care.”

- Regulating the behavior of the various participants in the system to preserve the integrity of health care markets and the safety of health-care products and services.

Most of the debate over health policy in this country has been over two questions.

First, to what extent should healthier or wealthier members of society be asked to subsidize the health care received by their poorer or sicker fellow Americans? Second, influenced by the answer to the first question, who should perform the functions listed above: government, private nonprofit entities or for-profit entities?

The Wyden-Ryan plan and similar precursors answer these questions as follows:

- Let government perform the second, third, fourth and sixth functions listed above (financing, risk pooling, assuring access to care, and regulating) but delegate the first and fourth functions (producing health care and “managing” its purchase) to the private for-profit or nonprofit sectors.

- Let there be a limit to the extent to which healthier or wealthier Americans are forced to subsidize the health care received by sicker or poorer Americans – that is, to the practice of social solidarity.

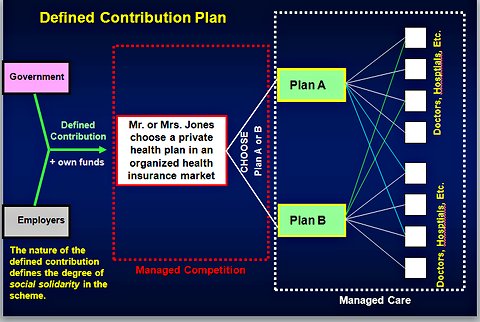

Together, these two responses may be called “truncated social health insurance.” The chart below illustrates it. Here an individual or a family is offered a choice between two health plans. In practice, such a menu could include many more competing plans.

Managed competition schemes, the Wyden-Ryan plan included, are typically operated through health-insurance exchanges of the sort provided in the Affordable Care Act. Rival health plans, which may or may not include a government-run plan, compete on this exchange under strict regulation of their behavior.

Each insurer must quote on the exchange the total premium it will charge for an assumed standard mix of actuarial risks and for a standard, defined package of health care benefits, as well as the portion of the total premium to be paid by the prospective insured.

Typically in these schemes, insurers cannot base their premiums on the health status and gender of the individual applicant and perhaps not even on age.

If government provides the defined contribution, as under the Wyden-Ryan plan, the health plan chosen by the insured will be sent by the government a premium contribution. In most designs, the contribution is adjusted for the actuarial risk the applicant represents, as best that can be done prospectively. It may also be means-tested, that is, tailored to the insured’s income.

There may also be ex-post risk adjustment, if, after the enrollment season, some some plans end up with risk that is more costly than average and other plans end up with lower-cost risk pools.

The major point of contention in the political debate over managed competition is not over these design parameters. Rather, it is over the nature of the “defined contribution,” which defines the extent to which the concept achieves social solidarity in health care. The crucial distinction here is between “vouchers” and “premium support” (as explained in Section B of this Brookings Institution document).

In a “voucher” system, the level and future time path of the defined contribution is set independently of the time path of the cost of health care per capita. If health care cost per capita in general rises faster over time than does the indexed voucher, the system naturally shifts more and more of health care costs onto the insured. That may be its chief objective.

The plan proposed earlier this year by Representative Ryan and passed by the House of Representatives on April 15 as part of its budget plan is a voucher scheme in this sense. In that plan, Medicare’s contribution to the private insurance purchased by Medicare beneficiaries was to be indexed to the Consumer Price Index, which historically has risen less rapidly than has health spending per capita.

The Wyden-Ryan plan is also a voucher scheme, because what it calls the “defined contribution” by Medicare is limited to the growth of gross domestic product plus 1 percent, adjusted for general price inflation. Historically, general health spending and Medicare spending per capita have risen at higher growth rates.

Alternatively, the defined contribution could be styled as a “premium support” payment whose time path is indexed to the growth in average health spending per capita (in the case of Medicare, per Medicare beneficiary) in a region.

The defined contribution in the Federal Employee Health Benefit plan enjoyed by members of Congress and federal employees is of this nature, as was the “premium support” in a plan proposed in 1995 specifically for Medicare by the Brookings Institution economist Henry Aaron and Robert Reischauer, then director of the Congressional Budget Office and now president of the Urban Institute.

Genuine premium-support models are designed to protect Medicare beneficiaries better against rapidly rising health care costs in general than would most voucher plans indexed to magnitudes that grow less rapidly than does health spending.

By the design of the defined contribution, the Wyden-Ryan voucher plan would be able to constrain the growth of taxpayer financing for Medicare, simply by shifting the risk of rapid health-care cost increases from taxpayers into the household budgets of the elderly.

As I noted in several earlier posts, the hypothesis that managed competition among private health plans can better control the overall health spending per Medicare beneficiary than would traditional Medicare lacks empirical support. It certainly has not worked that way in employment-based health insurance.

That hypothesis remains purely a belief.

Article source: http://feeds.nytimes.com/click.phdo?i=0357f5f6dbac3bf3370136f18ccdb2fd