The provision, known as the domestic production activities deduction, gave companies a tax break on income they earned from making things in the United States. It was intended to help American manufacturers, which were struggling to hold their own against competition from overseas.

Then a raft of other industries heard about the rule as it was being devised and fired up their lobbying machines. Suddenly, everyone became a manufacturer.

Movie studios got the break because they produced films, and tech giants won it, too, for making computer software. Construction companies got it for making buildings, and so did engineers and architects for designing them.

Starbucks hired lobbyists to make the case that it, too, was a producer, because the company roasts coffee beans. Congress added language that allowed coffee shops to deduct a percentage of every cup sold if it was made with beans they roasted off site. It became known as the Starbucks footnote.

“This has been a boondoggle tax expenditure,” said Robert J. Shapiro, a former Commerce Department official who founded the economic advisory firm Sonecon. “It is a political lesson. You are always liable to create tax loopholes that grow.”

The government initially estimated that the 2004 law would cost a net $27.3 billion from 2005 through 2014. It ended up costing over $90 billion during that period, according to a congressional report.

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

The Internal Revenue Service had to warn retailers that cutting keys doesn’t make you a manufacturer. Neither does mixing paint, putting plants in the sun to grow or writing “Happy birthday” on a cake you didn’t bake.

Interactive Feature

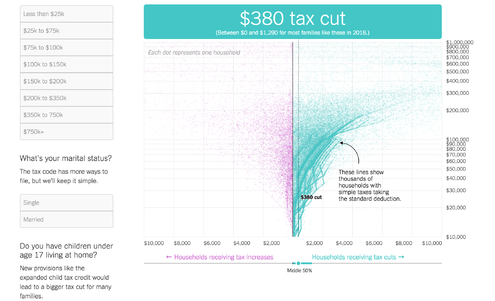

Tax Bill Calculator: Will Your Taxes Go Up or Down?

This simple calculator describes a range of tax scenarios under the Republican tax plan. Find households like yours in five steps or fewer.

But in more than a decade of battling with companies about the rule, the government gave up more ground than it won. One of its most epic losses came at the hands of a David-size challenger in Fullerton, Calif.

It all started in tax class. Dan Maguire, an accountant by trade, was sitting in a seminar about the new features of the tax code in 2005 when he first heard about the manufacturing deduction. He became obsessed.

“I’m thinking, ‘Gosh, as crazy as it is, this is a good deduction for Houdini,’” he said. Houdini Inc., better known as Wine Country Gift Baskets, is a plucky maker of assortments for special occasions that employs Mr. Maguire as its chief financial officer.

Newsletter Sign Up

Continue reading the main story

Thank you for subscribing.

An error has occurred. Please try again later.

You are already subscribed to this email.

Mr. Maguire filed for the deduction in amended returns for 2005 and 2006. The I.R.S. gave Houdini a refund of close to $300,000. Then, when it realized what had happened, it doubled back and audited the company, demanding that Houdini return the money.

“It’s the government — what do you expect?” Mr. Maguire said. “They aren’t exactly an efficiently run organization.”

When Houdini refused to give the refund back, the government sued the company in 2011.

At issue was a straightforward question: Does putting wine and chocolate into a basket amount to manufacturing? Federal lawyers sputtered at the thought.

“I can make a gift basket at home,” pleaded one government lawyer, according to a transcript in the case. “I can go to the store, and I can purchase these items and put them into a basket which I have purchased and put cellophane wrap around it, but in the process, I have not altered anything in it.”

Continue reading the main story

Article source: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/27/business/economy/tax-loopholes.html?partner=rss&emc=rss

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.